18 Section 2-3: The Accusative Case

2.3—The Accusative Case

So far in this chapter, you have been making sentences that have both subjects and direct objects.

Subject: the person or thing DOING the action

Direct object: the thing that gets the action DONE by the verb

Beispiel: Sein Vater trinkt gern Apfelsaft.

(subject) (verb) (direct object)

- Subject→sein Vater (the person doing the drinking)

- Verb→trinkt (the action)

- Direct object→Apfelsaft (the thing being drunk)

In Chapter 1, you learned that the subject of a sentence is in the nominative case. Now we will add to that; the direct object is in the accusative case.

Nominative case: subject

Accusative case: direct object

Normally, the direct object comes after the verb in German sentences, but not always! Remember, as you learned in Chapter 1, we can switch around different elements in a German sentence, as long as the verb remains in 2nd position. The direct object of each sentence below is in bold print.

Ich habe zwei Schwestern. I have two sisters.

Meine Tante hat einen Freund. My aunt has a boyfriend.

Unser Cousin trinkt kein Bier. Our cousin drinks no beer.

Wir spielen gern Fußball. We like to play soccer.

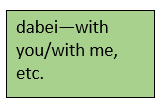

So far, you have been making several sentences that have direct objects, using words for food, drinks, and hobbies. Direct objects are in the accusative case. When we use definite articles (der/die/das) and indefinite articles (ein/eine), as well as possessive adjectives and negation (kein/keine) as direct objects, there are some slight changes.

NEU! You might have noticed an extra –en at the end of the word “einen.”

Meine Tante hat einen Freund.

Masculine words will add an extra –en to the definite article, indefinite article, possessive adjectives, and “kein.” (ONLY masculine! Everything else stays the same.) In the examples below, the extra –en has been bold-faced. The direct object has been underlined. The masculine examples have been prefaced with a *.

*Wir kaufen einen Kuli. (Masculine „Kuli“ adds –en.)

Du kaufst ein Heft. (Neuter „Heft“ stays the same.)

*Ich habe keinen Cousin. (Masculine “Cousin” adds –en.)

Er hat keine Tochter. (Feminine „Tochter“ stays the same.)

*Karin braucht meinen Gummi. (Masculine „Gummi adds –en.)

Ihr kocht meine Suppe. (Feminine „Suppe“ stays the same.)

*Du kennst seinen Enkel. (Masculine “Enkel” adds –en.)

Wir sehen die Kinder. (Plural “Kinder” stays the same.)

Der Student liest euer Buch. (Neuter „Buch“ stays the same.)

The definite article “der” becomes “den” in the accusative.

Frau Koltz kauft den Computer. Frau Koltz is buying the computer.

Du und ich lesen den Roman. You and I are reading the novel.

Sehen Sie den Mann? Do you see the man?

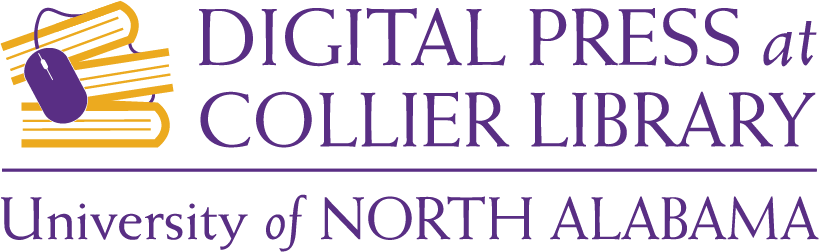

An easy way to practice using the accusative case is to use the verb haben to talk about which family members you have and don’t have.

Ich habe eine Schwester. (Feminine stays the same.)

I have a sister.

Ich habe einen Vater. (Masculine adds –en.)

I have a father.

If you don’t have certain family members, use the correct form of kein to say that you don’t.

Ich habe keinen Bruder. (Masculine adds –en.)

I have no brother.

Ich habe kein Kind. (Neuter stays the same.)

I have no child.

TYPICAL MISTAKE: After learning the accusative case, students often want to give every single masculine word in the sentence an extra –en. Don’t do it. It’s only for the direct object.

TYPICAL MISTAKE: After learning the accusative case, students often want to give every single masculine word in the sentence an extra –en. Don’t do it. It’s only for the direct object.

INCORRECT: Meinen Vater kauft den Computer.

CORRECT: Mein Vater kauft den Computer.

ONLY use the accusative case for a direct object, aka. the thing being done.

Video: Click the links to see me reteaching the accusative case.

Video: Click to watch YourGermanProfessor’s video reteaching the accusative case with lots of examples.

Video: Click to watch The German Professor’s video on the accusative case.

Video: Watch Easy German’s videos to see lots of examples of sentences that use the accusative case.

Ex. A: Beschreiben Sie Ihre Familie! Which family members do you have or not have? Go through the list in both Chapters 1 and 2, using the accusative case AFTER the verb haben, as in the examples on the previous page.

Ex. A: Beschreiben Sie Ihre Familie! Which family members do you have or not have? Go through the list in both Chapters 1 and 2, using the accusative case AFTER the verb haben, as in the examples on the previous page.

Beispiel: Ich habe eine Mutter. Ich habe einen Vater…usw.

LISTENING PRACTICE: Listen to Linda introduce herself and tell about which family members she has and which hobbies. You won’t understand everything, but don’t worry; you’re just listening for family members and hobbies for now. Then fill in the blanks with the correct answers. (Audio courtesy of Linda from AudioLingua.)

Now listen to Finn introduce himself and tell about family members. (Audio courtesy of Finn from AudioLingua.)

Ex. B: Was haben Sie dabei? What do you have with you today? Describe your items, using the verb haben and the accusative case.

Beispiel: Ich habe ein Buch, einen Kuli und ein Heft dabei. Ich habe keinen Laptop dabei.

Predicate Nominatives:

It’s easy to get in the habit of assuming that the last noun in the sentence is the direct object. Here are some instances where the last word is still in the nominative case. We call these predicate nominatives.

The verb sein (to be) is always followed by the nominative case. Any form of sein (ist, bist, sind, bin, seid) acts like an equal sign that makes one side of the sentence exactly equal to the other.

Das ist ein Kuli.

![]()

Therefore “ein Kuli” is nominative. We don’t put an extra –en at the end because it is not accusative.

Du bist mein Bruder.

![]()

Therefore “mein Bruder” is nominative. We don’t add an extra –en at the end because it is not accusative.

Video: Watch Easy German’s video to see lots of examples with both nominative and accusative. The first example will always be a predicate nominative, which you read about on the previous page, and the second will be in the accusative.

Now let‘s take it one step further. In the next exercise, you will have to determine whether the blank is in the nominative or the accusative before filling in the blank.

Step 1: Determine whether the word is in the nominative or accusative (aka subject or direct object.)

Step 2: If it is accusative, masculine adds an extra –en; der becomes den.

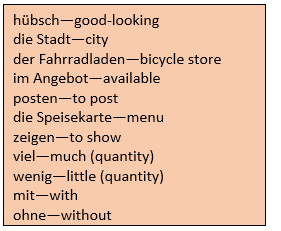

Ex. E: Was kaufen Sie am Semesteranfang? What do you buy at the beginning of the semester? Practice using the accusative case to tell a partner what you buy each semester. Remember, the things being bought are direct objects. Masculine items should get an extra –en.

A: Was kaufst du am Semesteranfang?

B: Ich kaufe einen Rucksack, viele Bücher und ein Heft.

KULTURECKE: Watch Deutsch im Blick’s video about shopping for groceries. Was kaufen Austin und Andrew? (Used with permission from The University of Texas at Austin | coerll.utexas.edu.)

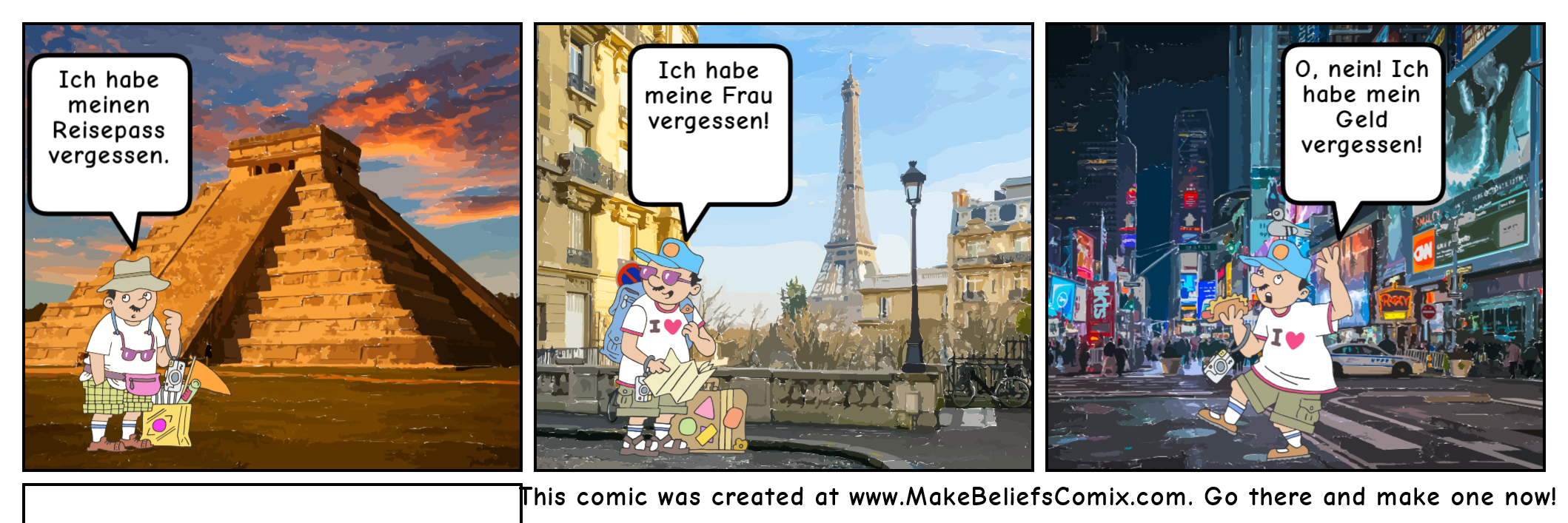

Ex. F: Was haben Sie heute vergessen? What have you forgotten today? Remember to put the items being forgotten into the accusative case because they are direct objects.

![]()

A: Was hast du heute vergessen?

B: Ich habe ________, _______ und _______ vergessen.

der Reisepass—passport

Ex. G: Video. Nicos Weg. Folge 11: “Adressen.” Click the link to watch episode 11. Then do the online activities with it. You will here a new verb, suchen, which means “to look for, search for.” You will also review question words. If you need a review, look back in chapter 1.

NOTE: Germans don’t ask WHAT a telephone number is but instead HOW a telephone number is→ Wie ist Ihre Telefonnummer? or Wie ist deine Telefonnummer?

https://learngerman.dw.com/en/adressen/l-37269671.

(Audio courtesy of Wikimedia user Jeuwre, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International.)

Ex. I: Video. Nicos Weg. Folge 12: Auf dem Amt. Click to watch episode 12 and do the activities following it. You will review du vs. Sie again, as well as formal and informal greetings and numbers in the hundreds.

https://learngerman.dw.com/en/auf-dem-amt/l-37269629.

https://learngerman.dw.com/en/auf-dem-amt/l-37269629.

Ex. J: Video. Nicos Weg. Folge 13: Was machst du hier? Click to watch episode 13 and do the activities following it.

https://learngerman.dw.com/en/was-machst-du-hier/l-37278679.

https://learngerman.dw.com/en/was-machst-du-hier/l-37278679.

Answers:

- deinen; Cousin is the direct object and masculine. Therefore “dein” becomes “deinen.”

- ihr/ihre; Both words are the subject. Enkelin is feminine, so therefore ihr + e = ihre.

- meine; The word is plural and the subject. Mein adds an e for plural.

- euer; The word is a direct object and neuter. Nothing changes.

- Ihre; Zeitung is the direct object and feminine. Ihr + e = Ihre.

- sein; Vater is the subject. I know it probably looks like it’s the direct object, but rephrase the question so that it’s a sentence: Sein Vater liest was. “His father reads what.” “What” is your direct object and father is the subject.

- unsere; Bücher is a plural word and a direct object. Unser + e = unsere.

- meinen; Onkel is the direct object and masculine. Therefore mein takes an extra –en because it changes in the accusative case.

- ihre; Kinder is a plural and a subject. “Ihr” + e = ihre.

- einen/eine; Both words are direct objects. The first is masculine and adds an extra –en in the accusative. The second is feminine.

- Der/den; In the first blank, it is the subject and stays “der.” In the second, it has become the direct object, and masculine direct objects in the accusative change to “den.”

More Extra Practice with Possessive Adjectives and Nominative vs. Accusative: (Courtesy of Claudia Kost & Crystal Sawatzky, University of Alberta.) Hint: you’ll have to use context to figure out whether it’s my, your, his, our…usw.

Extra Practice with the accusative case:

Click the links to do extra practice on Germanzone.org’s website. It will grade your answers automatically. If you want to do the exercise again, the site will give you different questions so that you can practice as much as you like.

- Nominative vs. accusative: https://www.germanzone.org/nominative-accusative-cases-mixed-determiners/.

- Identifying the direct object: https://www.germanzone.org/accusative-case-direct-objects/.

- Accusative case: https://www.germanzone.org/accusative-case-mixed-determiners-1/.

- Accusative case: https://www.germanzone.org/accusative-case-mixed-determiners-2/.

- Accusative case with new vocabulary; don’t be afraid to look up any words you don’t know. https://www.germanzone.org/accusative-case-possessive-adjectives/.

- Accusative case with indefinite articles: https://www.germanzone.org/accusative-case-indefinite-articles-1/.

- Accusative case with indefinite articles 2: https://www.germanzone.org/accusative-case-indefinite-articles-2/.

- More advanced accusative exercises: https://www.germanzone.org/accusative-case-definite-articles/.

- Subject, predicate nominative, or direct object? https://www.germanzone.org/subject-predicate-noun-direct-object-1/.

Es gibt + accusative

To say “There is…” or “There are…” in German, we don’t use the verb sein, as in English. Instead, we use the idiomatic expression, “Es gibt…”

Es gibt eine Familie.

Es gibt eine Familie.

The noun that comes after the phrase “Es gibt” MUST be in the accusative case. That means that anything masculine must add an extra –en to the definite article, indefinite article, or possessive adjectives.

Es gibt einen Vater und eine Mutter.

Es gibt einen Großvater und eine Großmutter.

Es gibt zwei Kinder und ein Baby.

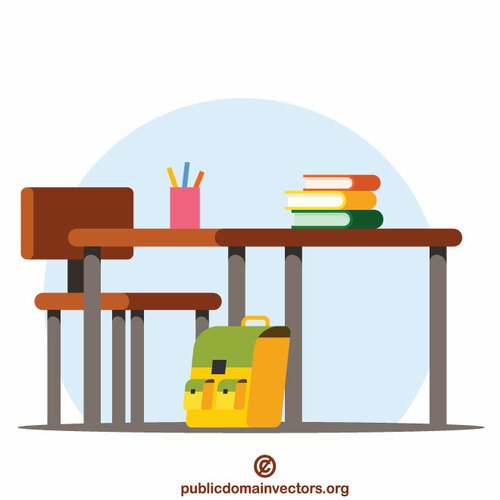

Ex. K: Was gibt es in diesem Zimmer? What is there in this room? Answer using “Es gibt” followed by the accusative case.

A: Was gibt es in diesem Zimmer?

B: Es gibt einen Tisch, _______, _______ usw.

Ex. L: Was gibt es in Ihrem Rucksack? What is there in your backpack? Answer using “Es gibt” followed by the accusative case.

A: Was gibt es in Ihrem Rucksack?

B: Es gibt ________, ________ und ________.

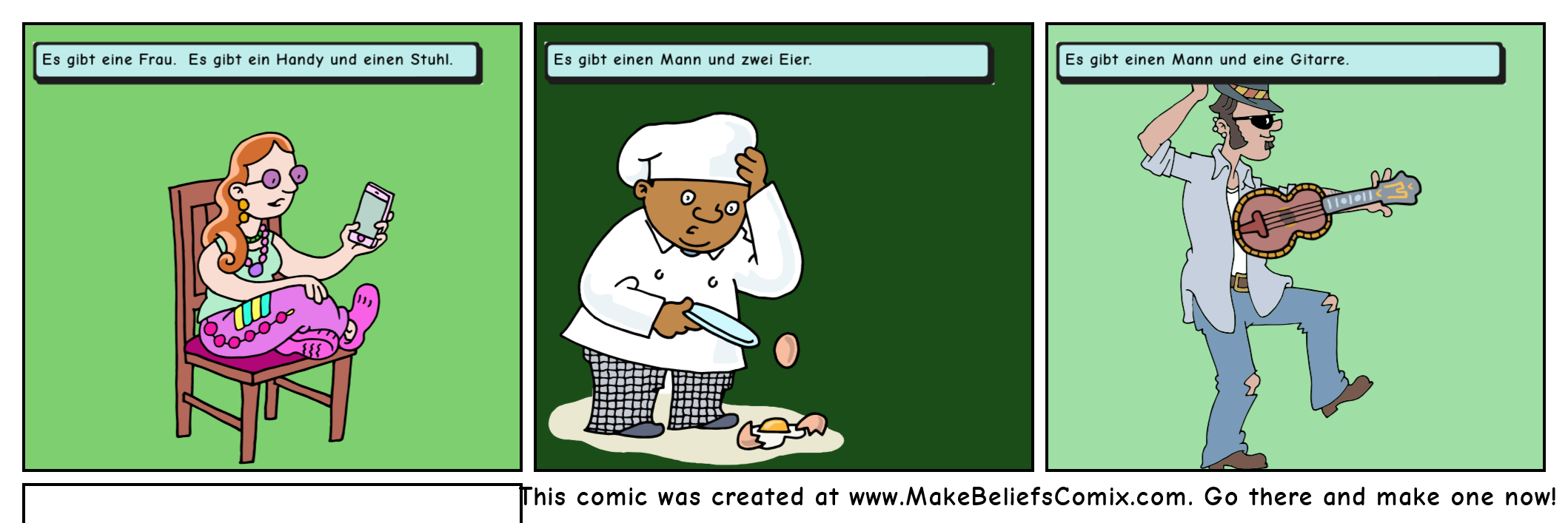

Ex. M: Was gibt es? Answer using as many complete sentences as possible for each picture.

-

“Classroom in Fort Christmas” by Photomatt28 is marked with CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Listen to Santiano’s hit song, Es gibt nur Wasser (2012), to hear the phrase “Es gibt…” used extensively. You will also hear the verb brauchen, which appeared earlier in this chapter.

Songtext: https://www.songtexte.com/songtext/santiano/es-gibt-nur-wasser-5b85230c.html

When dealing with direct objects and the accusative case, it’s good to know when to use a definite article or not. Often, in English, we don’t use a definite article.

I like to eat pizza.

There’s fruit here.

Notice that you don’t see the definite article “the” in these sentences. We aren’t talking about a specific pizza or specific fruit, so we leave it out. If you had been talking about a specific item, the sentences would have been

I like to eat the pizza. (specific pizza)

There’s the fruit here. (specific fruit)

If you normally wouldn’t use “the” in English, you probably won’t need der/die/das in German and vice versa.

Ich esse gern Pizza.

Es gibt Obst hier.

If you wanted to say that you’re eating a specific pizza or fruit, you would add the definite article.

Ich esse gern die Pizza. I like to eat THE pizza.

Es gibt das Obst hier. There’s the fruit here.

Use the English that you already know to help distinguish between using a definite article or leaving it out.

QUICK REVIEW: We haven’t reviewed verb conjugation in a while, so try Dr. Claudia Kost’s and Crystal Sawatzky’s (University of Alberta) verb conjugation verb ending quiz to see if you still remember. We’ll be conjugating verbs again in the next section of this book.

Ex. O: Video. Nicos Weg: Folge 14: Was trinkst du? Watch episode 14 of Nicos Weg and do the online activities following it.

https://learngerman.dw.com/en/was-trinkst-du/l-37279418.

https://learngerman.dw.com/en/was-trinkst-du/l-37279418.