2 Chapter 2 – S4 Theory and Framework

Project Theory and Framework

Research in its purest form can be defined as “the formal, systematic application of the scientific and disciplined inquiry approach to the study of problems” (Gay & Airasian, 2003). A theoretical framework in research further serves to “attempt to develop plausible explanations of reality” and also “to classify and organize events to explain the causes of events, to predict the direction of future events, and to understand why and how these events occur” (Kaci, 2015). When it comes to comprehensive school safety and security standards, there is no clear cut existing theoretical framework applicable specifically to the topic due to the both the underdeveloped nature of research within the field, as well as the applied and practical nature of school safety and security. While there are various theories within the field of Sociology, Criminology, and Criminal Justice (all with variable degrees of security related applicability) such as choice theory, conflict theory, restorative justice, and strain theory, none of these in and of themselves are particularly suitable in terms of the preventative nature and character of school safety and security since they primarily are concerned with the cause and effect relationship regarding crime and criminal activity which is merely a small subset of school safety and security concerns (Hall, 2011).

Similarly, given the educational nature of the environment within which this research was be conducted, consideration of various educational theoretical frameworks was also necessarily considered such as behaviorist, cognitive, and social learning theories and all clearly have some impact and applicability in terms of education and training related to school safety and security, but were ultimately found lacking in terms of the ability to encompass all aspects of the research. In short, while education and learning are the ultimate desired outcome within schools, it is only a small part of overall school safety and security in actual practice (Social Learning Theory, 2007).

Obviously, with the author conducting this research toward the fulfillment of a Doctorate degree in Emergency Management, it is appropriate and reasonable to consider the foundational theoretical framework of the EM discipline, the Comprehensive Emergency Management (CEM) cycle. Clearly, there is applicability of this traditional EM theoretical approach and indeed, the S4 standards themselves are primarily based on the CEM phases with the needed addition of the two additional components of “prevention” and “intervention” to allow for the incorporation of unique aspects of safety and security within the school environment. However, as with overall emergency management, when it comes to school safety and security, it is important to realize that a singular perspective can sometimes serve to limit proper understanding, explanation, and evaluation. For instance, even within the field of EM, CEM theory with its simplified four phases sometimes “has trouble capturing the wider political, economic and cultural explanations of disasters” (McEntire, 2004). As a result, the author sees similar limitations as being likely in terms of comprehensive school safety and security standards.

Therefore, in light of the lack of finding the aforementioned theories suitable in having the breadth, depth, and ability to adequately encompass the multifaceted and holistic nature of comprehensive school safety and security combined with the fact “that limited research was conducted in the area, and no framework or model existed that explained or aided the understanding of the phenomenon” (Elliot and Higgins, 2012), a more unique theoretical framework and research approach is desired in this case. As a result, the author seriously considered the use of a “Grounded Theory(GT)” approach, even given its limitations and criticisms from many traditional academic researchers. While it would have provided for the use of inductive enquiry as a means of generating a new theory and understanding of school safety and security from an unconstrained perspective, GT was ultimately rejected as a theoretical approach by the author. Although as a framework it did not seem to provide the holistic focus and clarity necessary to capture the actual experienced based nature of the research participants as they interacted and implemented the S4 program, certain aspects of the GT approach were incorporated into the qualitative portions of the research.

As outlined by Merriam and Simpson (2000), when it comes to an area such as school safety and security, and indeed the entire discipline of emergency management for that matter, “Ultimately, the value or purpose of research in an applied field is to improve the quality of practice of that discipline” (Jones, 2009). With the primary functions of both the security arena (to include school safety and security), and emergency management functions being primarily practical and pragmatic in nature, (i.e. designed to improve actual performance of tasks and conditions) the author realized that a theory that could encompass both the educational and knowledge based components of comprehensive school safety and security, as well as the more task driven and pragmatic components of applying and implementing specific measures and standards, would likely be the perfect fit.

With the author having a firm background based on prior career military experience dealing with adult learners and the education of soldiers and military members, it became clear that one of the common theories underpinning just about all military training and education – learning from the experience of actual doing – might provide an appropriate theoretical framework for this research. As a result, David A. Kolb’s (1984) “cyclical theory of learning,” as well as Ellen J. Langer’s (1998) “mindful learning theory,” were both considered as possible choices to provide the theoretical framework and consistency for this research endeavor.

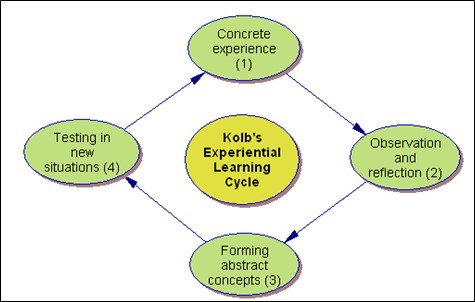

Figure 2.1 – Kolb’s Experiential Learning Cycle (Kolb, 1984)

According to Kolb (1984), the “cyclical theory of learning” provides a four-stage holistic perspective on education, training, and learning which involves the combination of experience, perception, cognition, and behavior to produce an interrelated model of how individuals grow, develop, and learn (figure 2.1). The major key distinction of experiential learning from other theories is the central role of experience in the learning process. For Kolb, “learning is the process whereby knowledge is created through the transformation of experience. Knowledge results from the combination of grasping experience and transforming it” (Kolb 1984, p. 41).

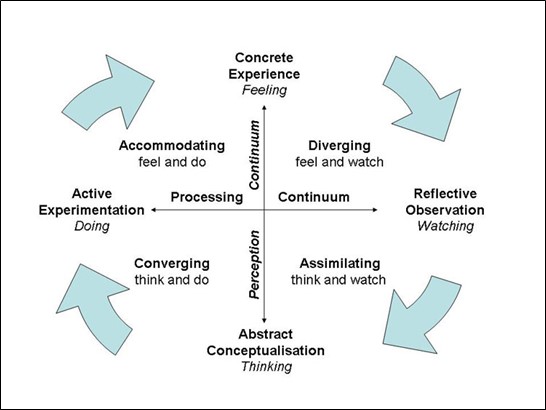

Figure 2.2 – Kolb’s Learning Continuum (McLeod, 2013)

This is particularly relevant in this research project as the researchers explore the impact and role of the experience of the participants with their implementation and assessment of their school environments, and use of the S4 standards as they transfer that experience into concrete knowledge and confidence regarding school safety and security. Additionally, this is even more applicable as the investigators assess the difference in the knowledge, confidence, and abilities of those participants who experience a full-profile school emergency exercise or a table top simulation exercise as a focusing event versus those who are only exposed to the standards in a more static and abstract way.

One of the key components and underpinnings of the experiential learning theory as defined by Kolb (1974), is the fact that different people will naturally gravitate to a particular style of learning that seems to work best for them. This preference is manifest and impacted by a number of factors such as one’s own educational experiences, the social environment that one is raised in and on the overall basic cognitive structure of the individual learner. Regardless of the influences upon particular style choices, Kolb suggests that the preference is actually an interplay between two sets of variables or two separate and distinct ‘choices,’ which can be represented and as distinct ‘lines of axis’ on a continuum with ‘conflicting’ modes or outcomes residing at each end as depicted in Figure 2.2 above (McLeod, 2013).

Kolb maintained that it is impossible to perform both variables from a single axis at the same time for instance, watching and doing or thinking and feeling. However, particular learning styles are derived from the product of the distinct choices which are made from a preference on each different axis for instance, the diverging learning style would be the choice of an individual who prefers to ‘watch’ and ‘feel’ as they learn. Realistically, it would be unusual for someone to exclusively use just one of the learning styles and indeed we find that “everyone responds to and needs the stimulus of all types of learning styles to one extent or another – it’s a matter of using emphasis that fits best with the given situation” (McLeod, 2013). As a result, the S4 standards and this research effort are designed in such a way to highlight each of the various learning styles during different phases and activities within the project. For instance, the initial stages of the S4 project includes the pre-test survey and familiarization training on the S4 standards and tends to favor the assimilating learning style with participants ‘thinking and watching’ as they complete those activities.

From there, the participants will hopefully use the standards for their own self-assessments of their classrooms, facilities and work areas which tend to favor the accommodating learning style with participants ‘feeling and doing’ as they complete the self-assessment activities. Selected participants will then engage in either facilitated table-top simulation exercises or alternately full-profile school safety and security exercises depending on the preference of the administration with these activities engaging the converging learning style as participants become engaged in ‘thinking and doing’. Finally, the external assessment and the posttest survey will engage the diverging learning style as participants will be ‘feeling and watching’ during the conclusion and wrap-up of the S4 activities. The expectation is that the fullness of the learning process will produce the results being explored in the research questions and as expected in the hypotheses being tested as outlined below in the research questions and hypotheses.

When it comes to school safety and security activities, as can be seen in the S4 standards, many of the tasks are fairly routine and involve daily tasks that can be conditioned from the proper application of policies and procedures. For many of the S4 activities involved in the Preparation, Mitigation, Prevention, and even Recovery standards, there is less concern with the particular learning style used by the individual because of the routine nature of the activities, the non-critical time constraints, and the ability to adjust as necessary to reach the ultimate desired outcome. When it comes to the Intervention and the Response standards, we find that in terms of a crisis situation the stakes can be quite different.

Within the school educational environment, obviously the main mission of the educator is to teach and instruct not to be an emergency first responder. However, in time of emergency or crisis, it is likely to be the classroom teacher who will be the critical factor in the successful outcome of the situation. In most cases, these individuals will (luckily) not have had much, if any, experience in actual crisis or emergency response and may not have the kind of ‘certainty’ described in Sophocles’ quote above. As Amanda Ripley describes in her 2008 work, The Unthinkable: Who Survives When Disaster Strikes – and Why, “We all share a basic fear response” (Ripley, 2008), and for the most part that fear is good in that it allows us to act quickly and instinctively when necessary due to imminent danger. However, as with the gift of fear, “for every gift that our body gives us in a disaster, it takes at least one away – sometimes bladder control, other times vision” (Ripley, 2008).

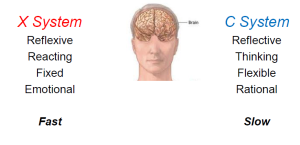

Ripley chronicles this in her book through a number of crisis and disaster event case studies based on interviews with thousands of survivors. She describes the natural response and reaction process that all of us go through when personally faced with emergency, disaster, or crisis. The first stage is ‘denial’ as our human brain tries to resolve a situation which is not normal and likely in chaos. We will tend to seek more information or look to others for reinforcement to determine what is happening; as a result, we tend to delay. The second stage is ‘deliberation,’ which involves the stark reality that something is, in fact terribly wrong, but we are not sure what to do about it – this is where fear usually enters the equation and the body begins to take those gifts away. The final stage is the ‘decisive moment’ when we decide to take action (or not) (Ripley, 2008). As mentioned previously, our body is programmed to give us some pretty incredible gifts in emergency and crisis situations, not the least of which is our natural ‘fight or flight’ survival response (less so with the freeze response). But as can be seen from the diagram below, there are two mental systems at work during this process. The first is our C system which is generally used in our general day to day activities and during the first stages of crisis response. It allows us to make good informed decisions based on sound analysis, but its downside is that it is slow and deliberative. Once fear and stress enter the equation during the ‘deliberation’ stage, our C system tends to begin to shut down or be constrained and our X system naturally takes over.

Figure 2.3 – The Brain Systems (Nichols, 2013)

In a crisis, as fear and stress increase we will begin to rely on our X system more and more. Therefore, where the C system would tend to be affiliated with the learning styles ‘diverging’ and ‘assimilating’, the X system is more in congruence with the ‘converging’ and ‘accommodating’ styles as we tend to automatically take action from a reflexive and emotional standpoint. The default X system responses are to fight, to flee, or to freeze. These are good responses but they tend to be unfocused in most cases (Nichols, 2013).

As mentioned previously, most teachers are not trained first responders and are not likely to have experience in dealing with many crisis and disaster situations. Ripley (2008), points out that this is also the case in the vast majority of disaster survivors as well. As Ripley (2008) and Nichols (2013) would point out, the critical component of crisis and disaster survival is one’s ability to keep the C system functioning as long as possible as well as one’s ability to have a positive, confident, and pragmatic attitude as to the outcome of the situation. That does not mean that fear will not be there, but simply put – making the decision that ‘you will survive at all costs’ can be a critical factor in survival and is indeed the most critical factor predicting survival as found by Ripley in her research. One of the ways to ensure that teachers’ C systems keep functioning as long as possible and that they are able to gather the positive and confident attitude in a crisis when needed, is to try and equip them with the tools and skills outlined within the S4 standards. Additionally, we should also strive to provide ‘converging’ and ‘accommodating’ experiential learning opportunities in the form of table tops and full profile school safety and security exercises and drills as suggested by this research project to increase their knowledge and confidence level in being able to act when necessary and to make good decisions when they do act.

As mentioned previously, the second theoretical construct that is relevant to the S4 project is Ellen J. Langer’s (1998), “mindful learning theory” as outlined in her primary work, The Power of Mindful Learning as well as in additional articles and papers. Langer maintains that much of what we do on a routine basis is done in a state of ‘mindlessness’, whereby we go through our day to day routines in such a way that we are unable to recognize the small and miniscule changes that occur around us that provide clues to future problems and issues (Langer, 1992). Obviously this is true in just about all human endeavors and is equally relevant to school safety and security.

In addition, one of the common findings during the S4 pilot project external assessments was that in many cases, school faculty and staff simply did not recognize some small vulnerabilities because they were accustomed to seeing them each and every day and did not notice the small changes as conditions deteriorated or deviated from the mandated standard. According to Veil (2011), “Langer (1989) suggests that individuals who follow the same routine every day without change become ‘mindless experts’ who concentrate on the end result and pay little attention to the process.” Moreover, Langer (1992), also mentions that “although change occurs all of the time, we typically only notice it when it is big enough to break up our comfortable routines.” The S4 standards in many ways seem to serve the function of breaking up these routines and overcoming barriers to the ‘mindlessness’ which is fairly common in educational organizations. In many cases Langer maintains that through mindlessness we become trapped by stability and routine, which “may help explain why we are frequently in error but rarely in doubt” (Langer, 1992).

‘Mindfulness’ (and the use of the S4 standards), on the other hand attempt to identify and overcome the barriers that tend to inhibit the ability to see warning signals well before they reach crisis or emergency situations (Veil, 2011). By completing the self-assessment with the use of the individual items outlined in the S4 standards, the intent is to get faculty and staff to approach their analysis and review in a ‘mindful’ manner and to hopefully overcome the barriers of familiarity and routine to provide a fresh look at solutions and possibilities for improvement. The open nature of the S4 standards that seek to define the ‘what’ of the outcome rather than the specificity of the ‘how’ that something must be done is seen as one of its strengths in encouraging ‘mindfulness’. “By taking into account the contexts, environment, and perspectives surrounding a situation and welcoming new information, mindfulness allows us to reframe the situation” (Veil, 2011). Reframing then enables the participant to view the elements and components of the process and correct any items which are incorrect or out of place.

While ‘mindfulness’ is important in the evaluation of the day to day and routine policies and procedures involved in school safety and security activities as outlined in the S4 standards, it is equally important in terms of preparing for crisis and emergency, as it allows for individuals to mentally consider options and prepare themselves for contingencies that may occur. The ‘mindful’ person is also in a better position to be able to have the knowledge and confidence in their own skills and abilities associated with the embrace of a positive and pragmatic attitude that has been previously discussed as being critical to having the ‘will to survive’ in a crisis setting. While ‘mindfulness’ alone may not allow an organization to “prevent a crisis once in motion (such as a natural disaster …), recognition of warning signals and vulnerabilities would allow for planning to minimize the consequences of the event when triggered” (Veil, 2011). The use of experiential learning experiences such as table tops and full profile school safety and security exercises as focusing events to provide experiential learning opportunities as outlined in the S4 concept seeks to provide a greater depth of knowledge, experience, and confidence through ‘mindfulness’ by overcoming the barriers to learning. Through this learning and experience in regard to school safety and security, the intent is to create conditions that “not only lessen the impact of crisis but also potentially prevent a crisis from occurring” (Veil, 2011).