1 Chapter 1 – Defining the Problem

Nature of The Problem: the right type and the right amount of help?

Because of the intense media coverage and high-profile nature of school shootings, it might be assumed that schools throughout the U.S. would be getting all of the help and assistance that they need to ensure complete and comprehensive school safety programs. However, in the words of one prominent school safety expert, Ken Trump, “the federal government has repeatedly since Columbine cut federal school safety funding” (Dedman, 2013) and while there have been renewed efforts and programs since the Newtown, CT school shootings, it is not completely clear what the state of school safety in the U.S. really is (Bergeron, 2013). According to Trump, “there’s always been a context of politics around this topic. The parents don’t know what they don’t know, and no one is rushing to tell them. There’s been a history of downplay, deny, deflect and defend … to protect the image of the schools” (Dedman, 2013).

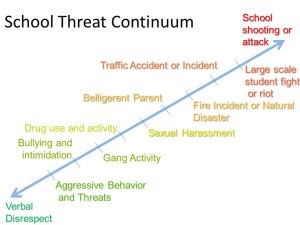

“There has been much discussion, information, and guidance concerning school safety and security in light of the many high-profile incidents over the past two decades. However, there has been an emphasis on active shooters, which tend to be low-probability incidents,” but they can have extraordinary consequences which is why they must be addressed (Bergeron, 2014, pg.16). However, many of the current safety and security practices and programs within schools today do not even begin to adequately address in detail the more common scenarios that are actually much more probable to occur and “that can be just as dangerous as, and result in as many or more fatalities than, an active shooter scenario – for example, tornadoes or other natural disasters, school bus traffic accidents, or a manmade catastrophe such as a train derailment of hazardous materials or chemical spill in close proximity to a school” (Bergeron, 2014, pg.16). The chart below (Figure 1.1) shows that the active shooter incident is just one (and the most unlikely) type of event that may impact a school’s safety and security on any given day.

Figure 1.1 – School Threat Continuum (Bergeron, 2015)

What does “right” even look like?

The reality is that a single research-based set of universally accepted standards regarding school safety and security currently does not exist. Albeit some states have either developed or are considering their own standards, but they vary widely in scope, scale, and applicability. Even at the federal level, there have been a number of studies on these issues by various federal agencies, but a single set of guidance and standards has yet to emerge that is widely accepted, much less researched and validated. In many cases, this may be due to an overall lack of empirical research into exactly what standards are most effective. There is also the issue of differences and variations between individual schools and districts that make a universal set of standards and guidelines a difficult proposition at best (Bergeron, 2014, pg.16).

Although the overall emergency management community has the Emergency Management Accreditation Program (EMAP) (http://www.emaponline.org/) and the National Fire Protection Association’s_NFPA_1600_standards_(http://www.nfpa.org/assets/files/AboutTheCodes/1600/1600-13-PDF.pdf) as a benchmark for overall EM programs, law enforcement has the Commission on Accreditation of Law Enforcement Agencies (CALEA®) and its voluntary accreditation program (http://www.calea.org/), however no such equivalent exists for school safety and preparedness. Therefore, a more suitable approach to consider for education is the possibility of “a broad-based set of voluntary school safety and security standards and guidance that allow schools and districts the flexibility to apply solutions within their own specific environment, culture, and resource constraints” (Bergeron, 2014, pg.16).

That is the basis for the research behind this guide in trying to validate the concept of the effectiveness of the use of a voluntary set of comprehensive school safety and security standards. Considering the lack of a national standard, the value of this guide is in the creation of a reliable and applicable programming and assessment tool that individual teachers, administrators, schools, and school systems can and will use to measure their readiness, preparedness, and overall safety and security in a comprehensive manner that compliments their unique school environment (Bergeron, 2013).

Purpose of the S4 Research: Mission and Vision

The mission of the School Safety and Security Standards (S4) Research Project and this guide is to assist K-12 institutions and school systems in proactively providing a safe environment, conducive to learning, where students and faculty can be free from safety hazards, hostile incidents, and other possible disruptions which can negatively impact the educational process and are prepared to appropriately react and respond in the event of emergency situations.

The vision for the realization of the School Safety and Security Standards (S4) Research Project and guide is the creation, implementation, exercise, and evaluation of the efficacy and effectiveness of a comprehensive school safety, security, and emergency preparedness program designed to provide education, training, services, resources, research, and most importantly, assessment tools for faculty and staff, administrators, school-based and community law enforcement emergency responders, and other stakeholders involved in school safety and emergency preparedness activities.

S4 Research Goals and Objectives

The results of the S4 project was first and foremost be to improve the security and safety of the teachers, administrators, schools, and school systems and of course, their students who choose to use the standards and the assessment process primarily through an increase in the knowledge and confidence level of faculty and staff in being able to deal with school safety and security situations that they may encounter. Secondly, the key goal is to be able to provide these standards and the assessment process freely without charge so that all educators can use it if they find these resources valuable. Finally, it is hoped that the results of this research and guide and the resulting standards program may eventually form the basis for a model for comprehensive voluntary school safety and security standards, training, and exercise programs that will be adopted by school districts, state departments of education, or a national organization such as the National School Resource Officers Association, or alternately provide for the formation of a non-profit – non-governmental organization dedicated to voluntary school safety and security accreditation.

The impetus for this project began in November of 2012, when the author applied for and received a Research and Development Grant from the University of North Alabama (UNA) College of Arts and Sciences, to conduct research in conjunction with the UNA Kilby Laboratory school on early emergency preparedness education. In the wake of the Newtown, CT Sandy Hook Elementary school shooting incident in mid-December 2012, by request of the Deans of the College of Arts and Sciences and Education, the scope of the project was expanded to look at overall school safety and emergency preparedness as well as expanding the program to all of the school systems within the greater Florence/Lauderdale area. The basic goals for the program were to conduct an initial pilot project to validate the efficacy of the School Safety and Security Standards (S4) as well as proper survey and assessment tools and observation techniques and processes as a proof of concept for the larger project (Bergeron, 2013).

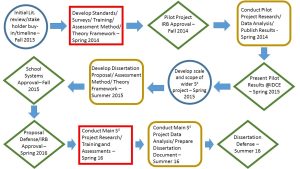

With the completion of the pilot project, it was determined that the overall S4 project was a feasible undertaking that had significant potential to increase the effectiveness of overall school safety and security and could provide the model for a statewide or even national program dedicated to voluntary comprehensive school safety and security standards on the order of EMAP, or CALEA. The program was then expanded to encompass more schools and more participants from throughout the K-12 system as outlined in Figure 1.2 in the chart below.

Figure 1.2 – Research Project Process Flowchart

Why “Standards” and not something else?

One of the interesting things discovered during the development of the S4 Project was, that depending on who one is talking to, (educators, law enforcement, EMs, etc.) the understanding of school safety and security can be very different based on their unique perspectives and experience. The same is true when the concept of “standards” is discussed and this seems to be related to the differences in perception between the actors involved in school safety and security. The use of the word “standards” as part of the title of the S4 project was initially chosen because that is what the states of Texas and Virginia call their school safety and security assessment guidelines which were key references for the S4 document and is also a familiar concept to most K-12 educators.

So, the question then becomes what exactly is meant by the word “standard”? Of course, the most pragmatic and simplest way to determine what “standards” means is to rely on the tried and true Oxford Dictionary, which defines a standard as 1) “a level of quality or attainment” or alternately 2) “a required or agreed level of quality or attainment” or finally 3) “an idea or thing used as a measure, norm, or model in comparative evaluations” (Oxford University Press, 2016). Additionally, if one consults the International Organization for Standard (ISO), arguably the premier expert entity when it comes to the topic of “standards,” their answer to the question of ‘What is a Standard?’ is pretty straight forward, describing a standard as “a document that provides requirements, specifications, guidelines or characteristics that can be used consistently to ensure that materials, products, processes and services are fit for their purpose” (ISO, 2016).

However, the confusion seems to become manifest when individuals interpret the concept of school safety and security “standards” either in isolation or based solely on their own experience or perspective. For instance, when an Emergency Management Director or EM Academic thinks about “standards,” they tend to come at the topic from an EM perspective and are thinking of a national level compulsory requirement, perhaps derived from the legislative mandates or regulatory guidance of the Department of Homeland Security or FEMA such as standards for floodplain management. However, with the S4 standards, a better analogy or comparison would be NFPA 1600 (called standards – but really more suggestions or guidelines) or EMAP (voluntary accreditation) or even the Certified Emergency Manager (CEM) ® certification program requirements. Of course, if the conversation is with law enforcement or School Resource Officers (SRO) the word “standards” would suggest something akin to CALEA ® – a voluntary accreditation program that an individual department can pursue. Similarly, a conversation about “standards” with firefighters will invoke a discussion of Public Protection Classifications (PPC)®, or ISO ratings from the Insurance Services Office. All of these can be considered “standards” but are very different in their scope, applicability, and implementation depending on their respective fields of practice.

However, when it comes to K-12 education – schools and school systems have standards for all kinds of things – some are mandated by the US Department of Education, or by the State Legislature or School Board, and deal with everything from school lunches to advanced level reading requirements, others are simply developed by districts and systems themselves or are adopted from non-profit or advocacy organizations and are more like best practices, objectives, or guidelines – but many are still called “standards.” It seems that “standards” are a comfortable concept to K-12 educators and most seem to like the fact that they can measure themselves against a concrete objective, guideline, or “standard.” To date, there has not been any objection or pushback from any of the Superintendents, Administrators, or Principals to the word “standards” as used within the S4 project – particularly when the word voluntary is included with them. Indeed, much of what is in the S4 assessment document are things that schools are largely already doing, but the main benefit to the S4 program is that it consolidates these criteria into one easy to use checklist format.

Ultimately, in terms of the research conducted under the S4 project model, while important in and of themselves (and derived from established existing State standards), the focus is less on the content of the actual S4 assessment document or instrument (the standards), but instead the true value and desired focus of the research is on the impact and experience that the process of the use and implementation of the “standards,” and the overall S4 program experience has on the knowledge, confidence, and ability of the participants using the standards and the assessment process regarding comprehensive school safety and security.

Importance and Scope of the Research

As noted previously, the overall purpose of the School Safety and Security Standards (S4) project study is “to determine the impact that a comprehensive set of voluntary school safety and security standards will have on the knowledge, attitudes, and confidence level related to school safety and preparedness of faculty, staff, and administrators in the K-12 setting” (Bergeron, 2015). This research is particularly important based on the fact that there currently does not exist a universal and comprehensive set of school safety and security standards nationwide. Various states within the United States have attempted to define such standards with the states of Texas and Virginia respectively having the most advanced efforts toward this goal (Texas State School Safety Center. 2012 and Virginia Center for School and Campus Safety, 2014). However, even considering these efforts and the fact that the most recent fiscal year U.S. federal budget dedicated over $125 million to five categories of school safety efforts, there is no definitive research that shows whether these type of investments and programs are actually doing what they are designed to do (U.S. Dept. Of Education, 2015).

While there is an inordinate amount of discussion and effort related to the topic of school safety and security and a corresponding commitment of significant money and resources in technology and equipment, it is not completely clear whether these efforts are enhancing overall comprehensive school safety and security. In fact one of the biggest concerns among many school safety experts is the fact that “many of the school safety and security measures deployed in response to school shootings have little research support” (Borum, et. al., 2010). Now a decade plus later, the picture appears to be no clearer than it was then. Having an access control policy, requiring badges, or having a dress code policy, are all important measures toward school safety, but if these measures are circumvented by faculty and staff out of convenience or simple apathy (as was found in some of the author’s pilot study research) they are worse than useless. If implemented school safety measures are too cumbersome and impede the school’s daily operational activities, or they are not considered and implemented in a comprehensive and holistic manner, they are actually worse than having no policy at all in place, since they may tend to imply a false sense of security when in reality, they create additional vulnerability.

For the scope of this research, the desire was to look at a study population consisting of elementary level, middle school level, high school level facilities from both public systems, as well as non-public schools for a total sample of 12 schools in order to evaluate the effectiveness and efficacy of the S4 standards themselves and to also explore possible differences in the learning outcomes and the confidence and knowledge levels regarding school safety and security of the participants based on whether they just received training on the standards or whether they participated in a table top or full profile exercise. The S4 project also hopes to provide a model for a possible voluntary school safety accreditation program at the regional, state or even national level akin to the EMAP program for Emergency Management, or the CALEA accreditation within law enforcement.