2 Chapter 2: Physical Characteristics

David grew up in small town Alabama in the 70s. His father was a machinist and his mother a stay-at-home mom. His mom ran the house, took care of the children, and supported her husband in his interests and endeavors. She had very specific ideas about how she wanted her children to look and behave. She expected them to be well-mannered, kempt, and productive members of society. One priority to her was her family’s appearance. She dressed them well and worked hard to keep their clothes neat, clean, and in good shape. These early influences followed David into his adult life. He never left the house without being ‘put together,’ nice jeans or slacks, button-up or polo shirt. Several years ago, he began working as a machinist at a large chemical plant. Initially his co-workers thought he was an “Undercover Boss,” from the television show, because he always dressed so well. Once they realized that David was actually the machinist for the company, and not a corporate executive, he was frequently told that he would be the next supervisor or leader. Their perceptions were based not only on David’s abilities and work ethic, but the way that he presented himself through his appearance. As it turned out, after a couple of years he indeed became the supervisor.

Our physical characteristics have a huge impact on the way that others perceive us and the way we perceive others. Some physical characteristics are stable and can’t be changed without invasive surgery, whereas others are easier to control and adjust. This chapter explores objective and subjective beauty standards, ways that appearance influences perceptions, artifacts that allow us to alter the perception we create (and perceptions about ourselves), the way that smells influence us and others, and related cultural and co-cultural influences.

Beauty Standards

Beauty is in the eye the beholder – or is it? This is a familiar phrase that I am sure you have heard. Dr. Michael Persky explains that there is an objective perception of beauty and a formula that can be used to determine beauty in the natural world (Hobbins, 2019).

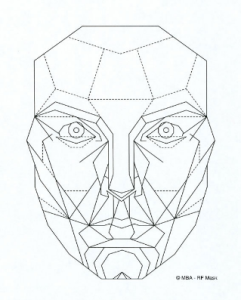

He stated that the Golden Ratio (ratio of beauty) is 1 to 1.618 – the ideal proportions of the human face. The specifics include: the length of the face is approximately 1.618 times longer than the width, the top of the nose to the center of the lips should be approximately 1.618 times the length of the top of the upper eyebrow to the lower eyelid, the length of the ear should be comparable to the length of the nose, and the width of an eye should be similar to the distance between the eyes (Maningas Cosmetic Surgery, 2019). The cosmetic surgery industry uses the Mask of Golden Ratio, which is based on this formula, as a guide. Some have even added that our eyes are naturally interested in and drawn to shapes with this ratio as support for its use (Victorian Cosmetic Institute, 2023). However, Britz (2022) explains that the golden ratio is a myth that is based on outdated and irrelevant information. He states that it represents only a small number of masculinized, Northwestern European women and when the formula is tested in the real world, it proves to be false. He does indicate that there are some standards that can be applied to beauty, but the touted Golden Ratio is not one of them.

It may be preferable, then, to view beauty as subjective, with the understanding that there are various interpretations. First, there is not a universal standard of beauty and perceptions of beauty often differ across countries (Sierminska, 2015). Second, what is deemed as attractive in one culture may go completely unnoticed in another. There are even criteria variations for attractiveness within our own culture (e.g. do you find brown eyes, blue eyes, or green eyes attractive? Curly hair, straight hair, long hair, short hair, etc.). Scholars have found that the most attractive faces tend to be the mathematical averages in a particular population and individuals closer to the average are often rated as more attractive. Additionally, the more positive exposures we have to a stimulus the more attracted we are to it (Knapp, 2014).

Last, other influences affect our perceptions of beauty. Media exposure creates agreement across society about attractiveness. Many advertisers are becoming more inclusive in their marketing because they recognize that individuals cannot make a connection to a product that they cannot see themselves using (Gynn, 2020). At worst, these motives are self-serving and intended to increase profits. At best, they provide representation that has been lacking in the past. The changing landscape of representation in the media contribute to changing perspectives about beauty and beauty standards.

Appearance

Even though there are various ways to define beauty, research has clearly demonstrated that we make positive associations for attractive individuals. Children rate attractive teachers as more qualified, however, physical attraction is attenuated by other nonverbal communication (e.g. soothing vocalics, etc.). Likewise, teachers tend to view attractive children as more intelligent, more socially adept, and more positive in their attitudes toward school. On the other hand, students who are not deemed as attractive tend to get blamed more (Knapp, 2014). Teachers are not the only individuals to perceive attractive individuals as more intelligent. However, this perception is merely that, a perception that is not based on factual information. Mitchem et al. (2015) looked at intelligence and facial attractiveness from an evolutionary perspective. They investigated the relationship between attractiveness and intelligence, which as they state, will be positively correlated according to evolutionary model predictions. However, they found no correlation between attractiveness and intelligence. Talamas et al. (2016) assessed beauty, perceived intelligence, and academic performance. They, too, found that there was no relationship between attractiveness and academic performance, but that there was a significantly large correlation between attractiveness and perceived intelligence, attractiveness and perceived academic performance, and attractiveness and perceived conscientiousness. This tells us that even though there is not a connection between attractiveness and intelligence, attractive individuals are still perceived to be intelligent.

Attractiveness not only impacts education and perceptions of intelligence, it impacts income as well. Parrett (2015) investigated the tipping behaviors of customers and their ratings of server attractiveness. She approached customers leaving five different restaurants and surveyed them. She found that the customers who had attractive servers tipped them more. She identified a “beauty earning gap” and discovered that attractive servers can make $1,261 more per year in tips than unattractive servers.

If you don’t think that your face meets the Golden Ratio or that others don’t perceive you as attractive (and being attractive is important to you) don’t dismay. There are various ways to perceive individual attractiveness. Likewise, there are strategies (other than surgery) that increase attractiveness.

Artifacts

Artifacts are physical items that we choose and display to communicate specific information about ourselves to others. Artifacts that alter physical characteristic perceptions include those objects we choose to wear or adorn that represent our personalities and convey a particular image. They include clothing, body piercings, jewelry, and even vehicles. The focus of this section is clothing because of its pervasiveness in communicating both complex and extensive information.

Our clothing choice impacts the impressions that we make, it conveys our personalities and affects our own actions and thoughts. The way we dress can communicate credibility or warmth. In academia, students rate professors who dress more casually as warmer (approachable) than those who dress more formally. In contrast, professors who dressed more formally were rated more competently than their informal counterpart – unless the casually dressed professor talked about their expertise (Oliver, 2022). Other research has shown that when an individual is dressed more formally, we are more likely to see them as credible and comply with their requests, even when the request is to enact deviant behavior (Knapp et al., 2014). Dressing according to context has the same influence on compliance. For example, a person who is dressed as a nurse will raise more money when soliciting donations for breast cancer than someone who is dressed in a suit. In this case, as well as in the general verbal/ nonverbal connection during an interaction, congruence matters.

Last, the clothes we wear also influence the way we perceive ourselves. Enclothed cognition is the psychological term for the systematic influence that the clothes we wear impart on our psychological processes. Adam and Galinsky (2012) measured student responses and perceptions while wearing a disposable white lab coat or their regular clothes. Student participants in the study were told that local officials were thinking about making certain clothes mandatory and they wanted to know what the students thought about the clothes. Students were assigned to a group that wore a white lab coat or to a group that wore their regular clothes (a lab coat hanging on the chair in the room so they could see it). Additionally, those who wore the lab coat were told that it was either a doctor’s coat or a painter’s coat. The students then completed a task to find differences in pictures as their sustained attention was measured by the researchers. The researchers found that “participants displayed greater sustained attention only when wearing a lab coat described as a doctor’s coat, but not when wearing a lab coat described as a painter’s coat or when seeing a lab coat described as a doctor’s coat” (pp. 921). This tells us that the clothing that we wear has an impact not only on the way others see us, but also on the way that we see ourselves and our abilities. The symbolic meaning of our attire affects our success in performing tasks.

Physical features used as objective beauty standards don’t adequately tell us what is beautiful. Other characteristics include, but are not limited to, personality, artifacts, and the average of facial features, combine to ultimately determine attractiveness individually and at the community level. Another way that we make assessments about others and our environment is through smell.

Smell

Have you ever been to New Orleans? If so, perhaps there are certain smells that you remember from the city. I have positive memories from there, some of which include the smells. My mother and I frequently went to Café Du Monde and even though I was only seven-years old when I lived in New Orleans, I still remember the warm aroma of the café’s beignets – the smell permeated the air – it was the smells of fresh yeast bread, sugar, and vanilla. Sometimes I’ll get a whiff of this familiar smell and it makes me immediately feel safe and warm.

Smell has a significant impact on the way that we perceive others. Some of the ways smell influences our perception is through the evaluation of others’ personality and the reduction of stress when exposed to a loved one’s smell. Sorokowska (2013) studied the way that smell affected prepubescent children’s and young adult’s perception of someone’s personality. Fifty adults were odor donors – 24 women and 26 men – and they wore cotton pads at their underarms for 12 hours. The donors were asked to refrain from scented soaps and fragrance, pungent food, alcohol, and tobacco products. After they turned in their cotton pads, the donors completed a questionnaire that rated their extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism, openness to experiences, and dominance. She had 75 children, and 75 young adults smell the odor samples and answer questions about their perceptions about the donor. Interestingly, the children and adults were able to accurately assess neuroticism of the donor (based on the donor’s responses).

Also, 51% of the children and 60% of the adults were able to identify the biological sex of the donor. Adults were able to accurately identify dominance, but children were not. The children nor adults were able to accurately rate extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, and openness to experiences. Hofer et al. (2017) studied stress, scent, and romantic partner’s reactions. She randomly divided 96 women, had them smell one of three scents (romantic partner, stranger, or neutral), exposed them to the Trier Social Stress Test, and measured their perceived stress and cortisol levels. Cortisol is the hormone that regulates our body’s response to stress. Women who were exposed to their romantic partner’s scent had lowered cortisol levels and reported reduced perceived stress. However, women who were exposed to the stranger’s scent exhibited increased cortisol levels.

Our health is also communicated through our body odor and odor attractiveness has been known to influence mate choice. Our food consumption influences our natural smell and the attractiveness of our natural smell. Zuniga (2022) contacted men with varying diets to volunteer to donate their sweat. They identified the men by one of three consumption categories: meats, fruits, and vegetables; vegetarians; predominant meat eaters. They then had them wear cotton shirts for 24 hours – the men were instructed to bathe in nothing but water and not to use any scented products for 24-hours before wearing the shirt. On the day that they wore their shirts they were also not to use any scented products. Additionally, they were asked to engage in at least 1 hour of exercise. Once the 24-hours were complete, they were instructed to seal their shirt in the bag given to them by the researchers. Heterosexual women then smelled the samples and rated the odor for pleasantness. They found that more fruit and vegetable intake resulted in more pleasant smelling sweat regardless of the sweat intensity; fat, meat, egg, and tofu intake was also associated with pleasant smelling sweat; and greater carbohydrate consumption was rated as stronger and less pleasant.

Cultural and Co-cultural Perspectives of Physical Characteristics

There are many variations in the way that beauty, attractiveness, artifacts, and smell are interpreted. This last section highlights some of the variations in understanding these concepts along a cultural or co-cultural continuum.

Ethnic Perspectives

Smell is not only a biological, psychological, and social phenomenon, it is also a cultural phenomenon. Western culture does not place a high value on the sense of smell. Did you know that there are individuals who were born without the ability to smell? If someone does not have sight, we say they are blind. What is the term for the lack of ability to smell? It is anosmia. If you didn’t know that, don’t feel bad, many don’t. Hopefully, the perception of smell as an inferior sense will change since we have learned to appreciate and approach the gift of smelling differently because of Covid-19.

Cultural perspectives vary in their perception of the importance of smells and also in the interpretation of different smells. Ferdenzi et al. (2017) explain that exposure to odors and the context that an aroma is smelled in has an impact on perceptions about that smell. In their study they used scratch-and-sniff smell cards for six different odors – wintergreen, lavender, anise, maple, strawberry, and rose. One specific difference emerged from the smell of wintergreen. Individuals from North America rated the smell of wintergreen more positively than Europeans. This makes sense when you consider that wintergreen is used in candies and sodas in North America, but are used in medicines in Europe.

Beauty and Attraction: Gender, Race, and Age

Females tend to respond to attractiveness differently than men and have better recall for clothing. Referring back to Parrett’s (2015) study of customers, servers, and tipping behaviors, they subsequently found that female customers were more likely to tip more to attractive servers overall, but especially the attractive female servers. Horgan et al. (2017) discovered that women are better able to recall the clothing that an individual is wearing and may be more accurate in eyewitness recount when looking for a suspect. However, this can also result in clothing bias – the tendency to falsely identify a person in a line-up based on similar clothing to the perpetrator.

It has been customary to use white faces predominantly when conducting facial studies on attractiveness. This can be seen in the study discussed earlier in the chapter – Talamas et al. (2016) only used Caucasian faces as stimuli for their study (as many researchers have done). However, other researchers are exploring diverse faces and challenging conventional measures of attractiveness. Facial symmetry has long been heralded as the standard for attractive faces. Farrera et al. (2015) tested the long-held notion that facial symmetry defined attractiveness; they specifically studied Mexican student perceptions. There were 123 participants, heterosexual Mexican college students from the National Autonomous University of Mexico. They rated 100 photographs (50 of men and 50 of women). Surprisingly, their results indicated that the students did not relate facial symmetry with attractiveness.

Research has also uncovered perceptions of bias against the naturalness of black women, specifically their natural hair in professional settings. Standards of professional appearance have historically been based on white benchmarks – straight hair. Dove co-founded the CROWN Coalition with National Urban League, Color of Change, and Western Center on Law and Poverty. Joy Collective conducted The CROWN Research Study for the CROWN Coalition. They surveyed over 2,000 women (1,017 Black and 1,050 non-Black), in the United States, aged 25 – 64, who were employed full-time in an office or had worked in a corporate office in the last six months. They found that “Black women are 30% more likely to be made aware of a formal workplace appearance policy” (Dove, 2019). Additionally, they found that Black women are more likely to receive formal grooming policies than non-Black women and fear scrutiny and discrimination based on their natural beauty. The key findings from the study indicate that Black women are “more policed in the workplace, feel their hair is targeted, and are consistently rated as less ready for job performance.”

Throughout history, the perception has been that as men age they become distinguished. Women, however, have not been granted the same positive regard for aging. Million-dollar industries have pushed the narrative that women’s appearance should remain as youthful as possible and that they should reject the aging process through a youthful appearance. Stewart (2022) observed a panel of individuals demanding that women should be seen regardless of age and identifying the many versions of beauty unrelated to birth date. Yasmin Warsame, a member of the panel, reported that in her country of Somalia age for women is seen as a sign of wisdom.

Generally, aging for women, has not been celebrated, but instead perceived as shameful and ‘unnatural’. Men were asked to rate the attractiveness of middle-aged women. When other men were around, or they thought their answers would be revealed, they gave her lower ratings. When other women were around and they thought their answers would be private, they rated the women higher (Knapp, 2014). There is great social pressure on physical appearance, more so with girls than boys in almost every society, and anti-aging spending globally in 2021 was approximately 62.6 billion (Petruzzi, 2023). Women over 50 discussed the double-bind that women should appear youthful, thin, unwrinkled, and non-grey haired while still being expected to ‘act your age’ (Hofmeier et al., 2017). However, in the same research study, many women over the age of 50 reported regret for the years they spent being dissatisfied with their appearance.

Summary

It is easy to see that physical characteristics greatly influence the way that others perceive us, as well as the way we see ourselves. Even though there are mathematical formulas to determine ideal beauty, the real formula for attractiveness depends on other factors, such as community average and exposure. Even smells affect our perceptions of context and other individuals. Last, many individuals are gravitating away from long-standing standards for appearance and are beginning to embrace their naturalness.

- Choose two weeks to alter your clothing – one week dress nicely everywhere you go and one week dress comfortably everywhere you go. Record other people’s reactions to you (e.g. friendliness, cooperativeness, compliance…).

- Interview six international students, from various countries, about smells that are pleasing or displeasing to them. Also inquire about the difference in smells they have recognized since they have been in the U.S.

- Choose random individuals over a week to compliment either something stable about their appearance or something changeable about their appearance. Record the results so that you can later evaluate any similarities or differences for the two conditions.

Dig Deeper

References:

Adam, H., & Galinsky, A.D. (2012). Enclothed Cognition. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 481(4), 918-925. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1016/j.jesp.2012.02.008

Britz, T. (2022). The Golden Ration Test for Beauty is Completely Bogus. An Expert Explains Why. Science Alert. https://www.sciencealert.com/expert-explains-why-the-golden ratio-test-for-beauty-is-completely-bogus

Cortisol. (2021, December). Cleveland Clinic. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/articles/22187-cortisol

Dove. (2019). Dove: The CROWN Research Study [Brochure]. Unilever PLC/ Unilever N.V.

Farrera, A., Villanueva, M., Quinto-Sanchez, M. & Gonzalez-Jose, R. (2014). The relationship between facial shape asymmetry and attractiveness in Mexican students. American Journal of Human Biology, 27: 387-396. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajhb.22657

Ferdenzi, C., Joussain, P., Digard, B., Luneau, L. Djordjevic, J. & Bensafi, M. (2017). Individual Differences in Verbal and Nonverbal Affective Responses to Smells: Influence of Odor Label Across Cutlures. Chemical Senses, 42, (1): 37-46.

Gynn, A. (2020, June 5). Diversity and Content Marketing: How Brands Can Be More Inclusive. Content Marketing Institute. https://contentmarketinginstitute.com/articles/diverse inclusive content-marketing/

Hobbins, K. (2019, November 18). The art of Assessment: What is Beauty? Dermatology Times. https://www.dermatologytimes.com/view/art-assessment-what beauty

Hofer, M., Collins, H. K., Whillans, A., & Chen, F. (2018). Olfactory Cues from Romantic Partners and Strangers Influence Women’s Responses to Stress. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. http://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/5AUZ8.

Hofmeier, S.M., Runfola, C.D., Sala, M., Gagne, D.A., Brownley, K.A. & Bulik, C.M. (2017). Body Image, Aging, and Identity in Women Over 50: The Gender and Body Image (GABI) Study. J Women Aging, 29, (1): 3-14. doi:10.1080/08952841.2015.1065140.

Horgan, T. G., McGrath, M. P., Bastien, C., & Wegman, P. (2017). Gender and appearance accuracy: Women’s advantage over men is restricted to dress items. Journal of Social Psychology, 157(6), 680–691.

Knapp, M.L., Hall, J.A. & Horgan, T.G. (2014). Nonverbal Communication in Human Interaction 8th ed. Wadsworth.

McGill University. (2016, November 21). Sniffing out cultural differences: Olfactory perception influenced by background and semantic information. ScienceDaily. Retrieved from www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2016/11/161121163143.htm

Parrett, M. (2015). Beauty and the feast: Examining the effect of beauty on earnings using restaurant tipping data. Journal of Economic Psychology, 49, 34-46. doi:10.1016/j.joep.2015.04.002.

Petruzzi, D. (2023, January 11). Value of the global anti-aging market from 2021 – 2027. Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/509679/value-of-the-global-anti-aging-market/#:~:text=With%20the%20market’s%20size%20amounting,billion%20U.S.%20dollars%20by%202027.

Sebastian Oliver, Ben Marder, Antonia Erz & Jan Kietzmann (2022) Fitted: the impact of academics’ attire on students’ evaluations and intentions, Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 47:3, 390-410, DOI: 10.1080/02602938.2021.1921105

Sierminska, E. (2015). Does it pay to be beautiful? Physically attractive people can earn more, particularly in customer-facing jobs, and the rewards for men are higher than for women. IZA World of Labor, 161, doi:10.15185/izawol.161.

Sorokowska, Agnieszka (2013). Assessing Personality Using Body Odor: Differences Between Children and Adults. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 37: 153-163.

Waddick, K. (2022, July). Pharma companies take a fresh approach to inclusion in new DTC ads. PharmaVoice. https://www.pharmavoice.com/news/pharma-advertising-approach-to-inclusion-Saphnelo-Tezspire-Amgen-AstraZeneca/626509/

Washington University St. Louis (2023, January). Race and Ethnicity Study Guide. https://students.wustl.edu/race-ethnicity-self-study-guide/#:~:text=Race%20refers%20to%20the%20concept,%2C%20heritage%2C%20religion%20and%20customs.

What is the Golden Ratio of Facial Aesthetics? (2022, June 16). Maningas Cosmetic Surgery. https://mcosmeticsurgery.com/what-is-the-golden-ratio-of-facial-aesthetics/#:~:text=A%20visually%20balanced%20face%20is,the%20lips%20to%20the%20chin.

Zuniga, A., Stevenson, R.J., Mahmut, M.K., & Stephen, I.D. (2017). Diet quality and the attractiveness of male body odor. Evolution and Human Behavior, (38), 136-143.