6 Chapter 6: Facial Expressions

Savannah and her husband, Michael, had been window-shopping trucks for about six months. They wanted a new truck but weren’t really committed to buying one. It was a great opportunity for them to spend some quality time together looking and dreaming, though. One day they were out, and Michael decided on a whim to stop in at a dealership and drive through their parking lot. He stopped at a truck that looked nice and as Savannah opened the driver’s side door of the new truck, a salesman approached them. She smiled back at him very quickly to communicate that she was friendly but really wanted to be left alone. However, she and Michael really liked the truck. They decided to inquire more about the price and went into the salesperson’s office. Savannah and Michael knew to manage their facial expressions carefully as they negotiated the price of the truck. The salesperson left to get an estimate on their trade-in and when he came back he offered over $2,000 more than what they expected. They quickly looked at each with a surprised look and then erased their expression as they turned to the salesperson. They bought the truck that day.

Take a few moments and look closely at these two pictures then answer the following questions. What are they thinking? Feeling? Do they look familiar? I know someone who looks very similar to the woman on the left. I know decidedly that it is not her because neither of these are pictures of actual people. They are computer generated faces (https://this-person-does-not-exist.com/en).

Take a few moments and look closely at these two pictures then answer the following questions. What are they thinking? Feeling? Do they look familiar? I know someone who looks very similar to the woman on the left. I know decidedly that it is not her because neither of these are pictures of actual people. They are computer generated faces (https://this-person-does-not-exist.com/en).

We pay a lot of attention to the face because it reflects our emotional state, our interpersonal attitudes, provides feedback to others, and some say it is second to speech for communication information (Knapp, 2010). The face reveals more information than any other part of our bodies and is a natural outlet for our emotional expression. Eibl-Eibesfeldt studied blind children in the 70s and found that they had similar nonverbal responses and facial expressions as sighted children. His research tells us that facial expressions are not learned through observation, but they are natural, and we learn display rules to control and regulate our expressions. In this chapter we will discuss some general information about facial expressions, stereotypes associated with the face, emotional expression through the face, and studies that identify specific facial configurations for the expression of emotion. As in every chapter, we will end with a discussion of the intersectionality of facial expressions and culture/ co-culture.

Anatomical Features of the Face

There are over 20 main muscles in our face. These “craniofacial muscles work together [in response to emotional stimulus] to control movements in your cheeks, chin, eyebrows, eyelids, forehead, lips, nose and nostrils, and ears in some” (Facial Muscles, 2021). These muscles, and the ability to communicate with them, is probably not something we ponder deeply over. Indeed, I’m sure that most of us take the ability for granted, me included. However, there are some individuals with underdeveloped sixth and seventh cranial nerves, the nerves that control eye movement and facial expressions. One of the effects of the underdeveloped cranial nerves is facial paralysis. This rare birth defect is called Moebius syndrome; researchers estimate that it affects 1 in 2-20 per million births (Moebius Syndrome Foundation, 2023). Facial paralysis prevents individuals from forming facial expressions – no smiles, frowns, or a raise of eyebrows. Facial expression is crucial to convey emotional communication, and so the inability to communicate with the face creates difficulties in social settings for those with the syndrome. Some ways that individuals have learned to communicate in the absence of facial cues is to reveal their personality through humor or to simply articulate their feelings, those that a conversational partner would likely read on their face if they were able to produce the expression (Bogart et al., 2012). Although not as severe, there are other static features of the face that affect communication.

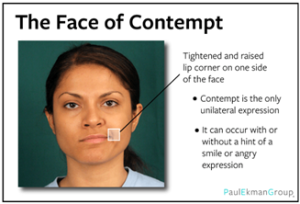

Some anatomical features in faces are often associated with specific stereotypes. Are you repeatedly asked if you are okay, irritated, or mad? If so, others might be forming impressions of your emotional state based on your facial features, which may or may not be accurate. Some individuals have facial features that give cues of negative emotions. For example, some people’s mouth raises at the corner on just one side when resting, which is an expression for contempt. Others’ mouths may turn down at the corners naturally causing them to seem sad. Plastic surgeons have coined the phrase “The Angry Face syndrome” for individuals whose features make them seem angry. Individuals with Angry Face syndrome have brows that are pressed down and down-turned corners of the mouth. Figure 1 is clipped from the article The angry face syndrome by Pastorek and White (2011). In the article they explain that the features of the angry face “project[s] a false social appearance of anger or at least annoyance…” (pp. 133). The angry face syndrome in plastic surgery is countered in pop culture with RBF. The reference is specific to a woman with harsh features or features that tend to make her seem like she is too serious.

Having facial features that make one’s face look as though they are scowling can have detrimental effects, but having features that are too pleasant isn’t good either. Jaeger and Meral (2022) found that individuals with “baby-faced features, a smiling mouth, and widely opened eyes” were rated as gullible (pp. 132). They also discovered that women were rated as more gullible than men, young people more gullible than older individuals, and “smiling individuals were seen as more gullible irrespective of their age” (pp. 142). On a more positive note, Knapp (2014) explains that some college students found facially expressive individuals more confident and likeable. Additionally, individuals with baby-faces tend to be judged less severely in court and individuals with soft facial expressions are more often found innocent or not guilty (Bal, 2022). These findings address the impact that one’s facial features (assumed emotional expressions) have on the onlooker, but it is important to understand that our facial expressions have an impact on us as well.

Facial Feedback Hypothesis

Darwin began the work on facial feedback and believed that if a person was permitted to freely express an emotion it would be intensified and emotional expressions that were suppressed would soften the experience of the emotion. Researchers have been studying facial feedback hypothesis ever since. Facial feedback hypothesis states that emotional expressions exhibited on the face will have an impact on the experienced emotion of the individual. In other words, if we smile we will feel happy. We don’t necessarily have to feel happy at first, if we will smile long enough our internal emotional state will become happy.

One of the ways researchers have studied facial feedback hypothesis is using pencil-in-the-teeth method. Holding a pencil with the teeth and spreading the lips forces a smile on the person’s face, whereas holding a pencil with the lips forces a more neutral to frown expression. One group of investigators had participants rate cartoons in one of these two conditions, pseudo smile or pseudo frown. The participants didn’t know the real purpose of the study, they were told that they were helping conduct research for writing instruments for disabled individuals. The researchers found that those who held the pencil in their teeth, creating a smile, rated the cartoons funnier than the other participants (Knapp, 2010).

As is customary among scholars, facial feedback hypothesis has been questioned and attempted to prove invalid. Some of the most recent work addresses the debate quite poignantly. Coles et al. (2023) tested facial feedback hypothesis by manipulating conditions of knowledge and perceptions of facial feedback hypothesis. In the first condition they told participants that they were testing the ability of facial poses to influence emotions. In the second condition, they told participants that they were seeking to demonstrate that posed facial expressions do not influence emotion. In the last condition they didn’t give any information about the goals of the experiment (this is a very brief summary of extensive work). However, they found that even those who believed that facial feedback hypothesis was incorrect still demonstrated facial feedback hypothesis effects!

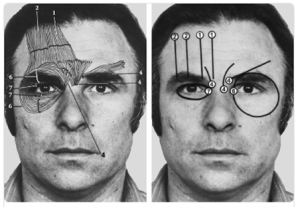

Facial Action Coding System

The Facial Action Coding System (FACS) is an intricate identification of facial movements and is a means to reveal the corresponding emotional implications in the face. Work on the system began in the early 70s by Carl-Herman Hjortsjo, was expanded by Ekman and Friesen in 1978, and significantly updated in 2002. In FACS, areas of the face are identified as action units (see Figure 2). Once movement in the action unit is identified, the emotional expression is discerned. This intricate system of observation and identification has been extremely useful in both understanding emotional expression in the face of others and the creation of emotional expression in animation. Ekman states that it led him to the discovery of microexpressions, which we will discuss shortly. It has been used as a tool for researchers (see for example Coplan, 2019; Barrett et al., 2019; Haj-Mohamadi, 2021; Davis et al., 2021), in therapeutic settings, and in animation. FACS coders require extensive training, but even the lay person can discern emotions in the face, and with education and practice, improve their decoding accuracy. It is necessary to begin with an exploration of emotions and the places they manifest in the face.

Emotions

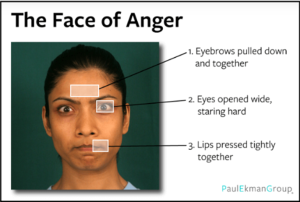

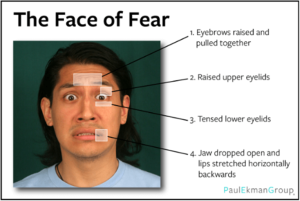

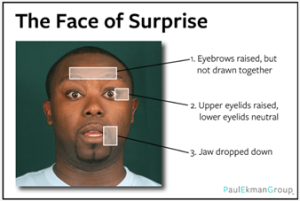

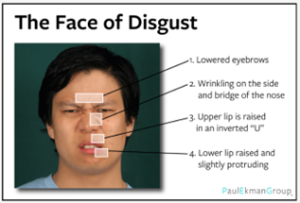

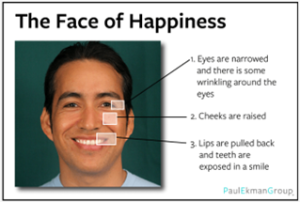

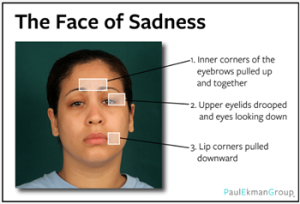

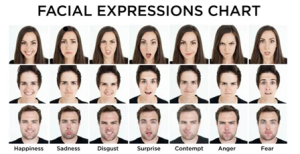

Universal Emotions. Ekman originally studied New Guinea individuals who had not had any exposure to the outside world – he wanted to observe ‘pure’ facial expressions. From this work, he identified six basic universal emotions and later added contempt. The universal emotions he has identified overall are: fear, surprise, disgust, anger, happiness, contempt, and sadness. He explains that whereas these emotions are universal, they are not single responses and are better understood as themes. For example, anger as a theme can vary in intensity – from annoyance to fury. Below are Knapp’s (2014) explanation of the facial expression displays and images from Paul Ekman Group website.

Anger. In anger the brows are lowered and drawn together and vertical lines appear between them. The upper lids are tensed and may or may not be lowered by the action of the brow. The eyes have a hard stare and may have a bulging appearance. The lips are in either of two basic positions: pressed firmly together, with the corners straight or down, or open and tensed in a squarish shape, as if shouting. The nostrils may be dilated, but this is not essential to the anger facial expression and may also occur in sadness. There is ambiguity unless anger is registered in all three facial areas (Knapp, 2014, pp. 280).

Fear. The brows are raised and drawn together. The wrinkles in the forehead are in the center, not across the entire forehead. The upper eyelid is raised, exposing the sclera, and the lower eyelid is tensed and drawn up. The mouth is open, and the lips are either tensed slightly and drawn back or stretched and drawn back (pp. 279).

Surprise. The brows are raised so they are curved high. The skin below the brow is stretched, and horizontal wrinkles go across the forehead. The eyelids are opened: the upper lid is raised, and the lower lid is drawn down.; the white of the eye-the sclera- shows above the iris and often below as well. The jaw drops open so the lips and teeth are parted, but there is no tension or stretching of the mouth (pp. 279).

Disgust. The upper lip is raised. The lower lip is also raised and pushed up to the upper lip, or is lowered and slightly protruding. The nose is winkled, and the cheeks are raised. Lines show below the lower lid, and the lid is pushed up but not tense. The brow is lowered, lowering the upper lip (pp. 280).

Happiness. The corners of the lips are drawn back and up. The mouth may or may not be parted, with teeth exposed or not. A wrinkle, the nasolabial fold, runs down from the nose to the outer edge beyond the lip corners. The cheeks are raised. The lower eyelids show wrinkles below them and may be raised but not tense. Crow’s-feet wrinkles go outward from the outer corners of the eyes (pp.281).

Sadness. The inner corners of the eyebrows are drawn up. The skin below the eyebrows is triangulated, with the inner corner up. The upper eyelid inner corners are raised. The corners of the lips are down, or the lips are trembling (pp. 281).

Contempt. A slight tightening and raising of the corner of the lip on one side (Knapp, pp. 316). Contempt is the only expression that only shows on one side. Contempt is different from disgust. Contempt is akin to a feeling of superiority and may or may not be pleasant. Some individuals enjoy feeling powerful and superior. Disgust, on the other hand, causes us to want to distance our self from the source of disgust, perhaps turn our head away from or even leave.

Emotional Blends. In contrast to themes, emotional facial expressions can also be understood as blends. Cognitive scientists found it limiting to only use the six (original) universal emotions to analyze facial expressions, so they conducted research and added several compound emotions based on blends of the original universal six. For example, happily surprised is one of the blends they found. Savannah and Michael’s reaction to being offered more money for their car is a good example. Another one might be a surprise party. If you have ever had one and it made you happy then you also understand the blend of happily surprised. I don’t like surprise parties, so my facial expression may look more like fearfully surprised. Individuals with PTSD are more attuned to anger and fear and may display the blend angrily fearful. Here is the list of compound emotions identified by Martinez (2014):

-

-

-

-

- · Happy

- · Sad

- · Fearful

- · Angry

- · Surprised

- · Disgusted

- · Happily surprised

- · Happily disgusted

- · Sadly fearful

- · Sadly angry

- · Sadly surprised

- · Sadly disgusted

- · Fearfully angry

- · Fearfully surprised

- · Fearfully disgusted

- · Angrily surprised

- · Angrily disgusted

- · Disgustedly surprised

- · Appalled

- · Hatred

- · Awed

-

-

-

In addition to the 21 compound emotions listed above, they found a disagree emotion, which manifests in the face in the same way as anger (furrowed brow), disgust (raised chin), and contempt (tightly pressed lips). They had 158 Ohio state students participate in their study. They sat them in front of a camera and recorded their reaction to the statement: “A study shows that tuition should be raised by 30%. What do you think?” Virtually every student made the “Not Face”. What expression would you make to the same question? That’s more than likely the “Not” face.

Emotional Expression Styles

All of this information helps us to be better decoders of information and cues. However, a clear understanding of someone’s emotions relies on their effectiveness as encoders. If you have ever met someone you couldn’t quite figure out, it may be because of their individual emotional expression style. Cultures have display rules for the expression of emotion, but sometimes the display rules are more personal. Knapp (2010) identifies various individual styles as:

- The withholder – little facial movement

- Revealer – always expresses feelings

- Unwitting expressor – thinks feelings masked, but it isn’t

- Blanked expressor – thinks a feeling is being portrayed but others see a blank face

- Substitute expressor – separate than thinks is being displayed

- Frozen-affect expressor – genetics or habitually expressing emotions

Successful social interactions rely on our ability to understand and infer the intentions and emotions of others (Bal, 2022). Understanding that there are various styles of expression will help us adapt our perception and more effectively decode cues, especially when there are very little cues to go by.

Culture and Co-culture

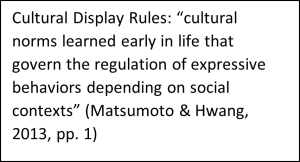

Western and Eastern Cultures

It might surprise you to know that the outward display of facial expressions are not universal – their use depends heavily on cultural display rules. Even though there are universal expressions, cultural display rules govern when and how those emotions are expressed. Hekiert et al. (2016) compared smiling, expression of optimism, and subjective well-being between Polish and Canadian citizens. They measured the number of times that each respondent smiled and their positive expression. They found that Canadians “smile more and express more positivity than Poles” (pp. 462). However, when they measured for actual life satisfaction and well-being, Poles scored higher than their Canadian counterparts. In Asian cultures, the expectation is that emotional expression is contained until confirmation and agreement with the larger group. Some research has indicated that East Asians who frequently reveal their emotions are seen as immature and inappropriate. In contrast, in Western culture the expectation is that individuals communicate openly and directly, therefore, they are encouraged to display their true emotion (see Ji et al., 2022). Fang et al. (2022) studied differences between high-context and low-context cultures and their expression of anger and disgust. They compared posed and spontaneous responses of participants from the Netherlands and from China. In the first condition (posed) they had participants make an angry or disgusted facial expression as if they were trying to communicate what they were feeling to a friend. Once the facial expressions were complete, they had participants review and choose the one that they felt most adequately displayed the emotion they were posing to ensure that they had the most accurate sample to analyze. The researchers found that the posed facial expressions of the Dutch participants were more distinct than the Chinese. As you can see, cultural expectations predict when and how individuals display both positive and negative facial expressions. Culture also affects the way that facial expressions are decoded. Saito et al. (2022) researched cultural differences between Japanese and American participants in their understanding of emotions displayed in the face while the sender was wearing a mask. They found that the Japanese participants were more accurate in identifying happy masked faces, but masks improved Americans ability to recognize fearful faces.

Sexual orientation

Perceptions of an individual’s sexual orientation are often judged by their facial expressions. Many studies have demonstrated that perceptions of gay men are shaped by their smiling frequency – men who smiled more are perceived to be more feminine, men who are perceived as more feminine are perceived as gay. Additionally, women who display more angry emotions are more likely to be perceived as lesbian. Bjornsdottir and Rule (2020) found that facial cues differ between perceptions of the sexual orientation of men versus women. They found that when men and women display facial expressions that are not gender typical (or deviate from social norms) they are more likely to be perceived as gay or lesbian. However, they found that participants had a more difficult time identifying lesbians by facial expressions. Indeed, Wang and Kosinkski (2017) explain that even though there are facial cues that indicate sexual orientation humans are poor judges. However, using a computer classifier, it accurately distinguished heterosexual men from gay men with 81% accuracy and heterosexual women and lesbians with 71% accuracy. They go on to state that the use of computer algorithms by companies and governments should pose concerns to these men and women.

Look at the pictures above. Can you tell which person is gay by looking at their facial expression? If not, don’t be dismayed. Although some can accurately identify someone’s sexual orientation from vocal and nonverbal behavioral cues, most people are not good at identifying sexual orientation based on the face; although, men tend to be better than women (61% to 54% respectively). It is well-known that there is an expectation or stereotype that expressions of happiness are associated with femininity. There is also a perception that the expressions of gay men are like straight women, and the expressions of gay women are like straight men (see Gieger et al., 2006). Bjornsdottir and Rule (2020) took neutrally posed photographs of 32 lesbians and 32 straight women and manipulated their facial expressions to show anger, neutrality, and happiness. Participants were shown one of the target images and instructed to rate the likelihood of the person in the image being gay or straight. The images that were angry were more often rated as lesbian. This only applied to anger, though. Happy faces were not associated with straight or lesbian women. Computer vision algorithms, however, have been shown to be highly accurate at identifying gay men and women by fixed (e.g. nose shape) and transient (e.g. grooming style) facial features alone (Wang & Kosinski, 2018). The accuracy of identification from a single image was 81% for the identification of heterosexual or gay men and 74% for women. When five images were entered, accuracy increased to 91% and 83% respectively.

Summary

Facial expressions are one of the first things we tend to look at when we want to understand how someone is feeling. Some individuals are very good at masking their facial expressions, but other’s emotions are more easily observed in their face. There are universal expressions and blends of these expressions that communicate consistently across cultures. However, the when and how emotions are expressed greatly depends on cultural display rules.

- Smile exercise – don’t smile for a day unless you are truly happy about something, make note of situations that you would normally smile in and how frequently you smile.

- Smile at every person you see (unless something bad is happening to them). At the end of the day, how do you feel?

- Make a purposeful effort to notice the amount of touch you give versus the amount that you receive. Are there any individual’s touch that makes you feel comforted? Why?

Dig Deeper

References

21 facial expressions identified (2014, April 1). SBS News. https://www.sbs.com.au/news/article/21 facial-expressions-identified/yl1fd1xwz

Barrett, L. F., Adolphs, R., Marsella, S., Martinez, A. M., & Pollak, S. D. (2019). Emotional Expressions Reconsidered: Challenges to Inferring Emotion From Human Facial Movements. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 20(1), 1–68. https://doi.org/10.1177/1529100619832930

Bjornsdottir, R. T., & Rule, N. O. (2020). Emotion and Gender Typicality Cue Sexual Orientation Differently in Women and Men. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 49(7), 2547 2560. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-020-01700-3

Bogart, K. R., Tickle-Degnen, L., & Joffe, M. S. (2012). Social interaction experiences of adults with Moebius Syndrome: A focus group. Journal of Health Psychology, 17(8), 1212 1222. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105311432491

Coles, N. A., Gaertner, L., Frohlich, B., Larsen, J. T., & Basnight-Brown, D. M. (2023). Fact or artifact? Demand characteristics and participants’ beliefs can moderate, but do not fully account for, the effects of facial feedback on emotional experience. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 124(2), 287–310. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspa0000316.supp (Supplemental)

Coplan, R. J. and W. M. (2009). Shy and soft spoken. Infant and Child Development, 18(6), 238–254. https://doi.org/10.1002/icd

Facial Muscles, (2021, August 4). Cleveland Clinic. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/body/21672-facial-muscles

Fang, X., Sauter, D. A., Heerdink, M. W., & van Kleef, G. A. (2022). Culture Shapes the Distinctiveness of Posed and Spontaneous Facial Expressions of Anger and Disgust. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 53(5), 471–487. https://doi.org/10.1177/00220221221095208

Haj-Mohamadi, P., Gillath, O., & Rosenberg, E. L. (2021). Identifying a Facial Expression of Flirtation and Its Effect on Men. Journal of Sex Research, 58(2), 137–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2020.1805583

Hekiert, D., Safdar, S., Boski, P., Krys, K., & Lewis, J. R. (2016). Culture Display Rules of Smiling and Personal Well-being: Culture Display Rules of Smiling and Personal Well-being: Mutually Reinforcing or Compensatory Phenomena? Polish-Mutually Reinforcing or Compensatory Phenomena? Polish-Canadian Comparisons. Unity, Diversity and Culture, 460–464. https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/iaccp_papers/157.

Ji, E., Son, L. K., & Kim, M. S. (2022). Emotion Perception Rules Abide by Cultural Display Rules: Koreans and Americans Weigh Outward Emotion Expressions (Emoticons) Differently. Experimental Psychology, 69(2), 83–103. https://doi.org/10.1027/1618-3169/a000550

Lewis, M. B. (2018). The interactions between botulinum-toxin-based facial treatments and embodied emotions. Scientific Reports, 8(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-33119-1

Matsumoto, D., & Hwang, H. (2011). Cultural Display Rules. The Encyclopedia of Cross Cultural Psychology, 303–304. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118339893.wbeccp126

Moebius Syndrome (2022, December 8). National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. https://www.ninds.nih.gov/health-information/disorders/moebius syndrome#:~:text=about%20Moebius%20syndrome%3F,What%20is%20Moebius%20syndrome%3F,eye%20movements%20and%20facial%20 expression

Moebius syndrome (2016, April 1). National Library of Medicine. https://medlineplus.gov/genetics/condition/moebius-syndrome/#frequency

Moebius Syndrome Foundation (2021, February 10). Interview with Rebecca and Jessica Maher. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=by6f-WBy7es&t=102s

Nope (2017, June). Ohio State Insights: Life and Society. https://insights.osu.edu/life/not-face

Pastorek, N. J., & White, W. M. (2011). The angry face syndrome. Archives of Facial Plastic Surgery, 13(2), 131–133. https://doi.org/10.1001/archfacial.2011.14

Saito, T., Motoki, K., & Takano, Y. (2022). Cultural differences in recognizing emotions of masked faces. Emotion. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0001181

The Definitive Guide to Reading Microexpressions (Facial Expressions). (2023, February 3). Science of People. https://www.scienceofpeople.com/microexpressions/

Wang, W. & Kosinski, M. (2017). Deep Neural Networks Are More Accurate Than Humans at Detecting Sexual Orientation From Facial Images | Stanford Graduate School of Business. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology (in Press), 114(2), 246–257. https://www.gsb.stanford.edu/faculty-research/publications/deep-neural-networks-are-more-accurate-humans-detecting-sexual

Universal Emotions (2023, February 15). Paul Ekman Group. https://www.paulekman.com/universal-emotions/