18 What is a caesura?

The word caesura comes from the tyrant, from tyranny’s warping of language. Behind the sound, there is an etymology that begins with the Roman empire led by Caesar.

When the imperial Caesar speaks, the pauses between lines and clauses gesture towards the implication of his words. The silences of Caesar are as powerful as his verbs.

In the country of the poet’s birth, school children are taught to worship the dictator.

When the tyrant speaks, his pauses signal new purges. The audience listens closely for new keywords that indicate a shifting discourse. The censors must be cartographers: they must devise maps to track the changes in borders between words that are permissible and words that must be banished from the republic.

Fashioning himself a Caesar, the Romanian dictator developed the caesura into a language of silent significations. The dictator’s pauses were ominous, dangerous, and indecipherable.

In poetry, the word “caesura” traditionally refers to a break in a metrical line that comes after the 2nd or 3rd beat. In modern verse, however, a caesura is usually taken to mean a pause near the middle of a line, an interruption, or a break inside a line.

The caesura’s power exists as a form of stickiness, the way in which associations and linked words are allowed to connect and cohere. In an essay or musical composition, the interlude enacts a sort of intentional silence which enables cohesion. We notice it as a pause, or a shift in direction, but it is also a moment of silence that allows us to hear the symphony of aluminum cans attached to the rear bumper of a car that just flew past.

Music is central to my understanding of the caesura’s connection to the cadence. An imperfect (or half) cadence is a pause. In poetry and prose, the half cadence is represented with a comma or a semicolon. The half-cadence’s rhythm refuses to sound final; it causes the line to end in the tension generated by indecisiveness. A perfect (or authentic) cadence comes at the end of a phrase in a poem.

The incompleteness is acknowledged, a person draws closer to a true story, or the one that will go on without us, the story of what we lacked. You can taste the tension between the need to be right (or affirmed as valid in one’s statements) and the freedom buried inside lack of such affirmation.

When I say lack, I mean the grief of what we won’t live to write. Poetry is a way of being, surviving, and relating to the experience of life.

You asked me about caesuras. . .

There are three ways of telling this story, or three ways of representing a rupture.

The first way of seeing the caesura is visual and grammatical, as exemplified by the ellipsis that cuts off the thought in the preceding sentence.

The second way of seeing the caesura involves a memory from Transylvania. The year is 1990. The old man is stretched on the massive dining room table, one foot towards the open door, his detachable wooden leg posed beside it. But the leg is not detached so much as it is unattached—loosely affiliated by silhouette. All three windows are open so his spirit can leave when the time comes. The buzz of bees mingles with the agitprop of a loose rooster.

“He will know,” my mother says. “The dead recognize the world they are leaving. The dead may be dead, but they are not finished. The man is still doing things.”

Two coins are laid over his eyes to pay the ferryman that will carry him over the river to the next life. All knives have been removed from the house, lest his soul hitch a ride on a blade and cut itself off from eternity. Three women in wool skirts sit next to the wall, their hair covered by scarves, their faces torn by wails and intricate moaning sequences. They will continue to wail for three days and three nights, covering the room with stories of praise for the man’s life, his successes, his good harvests, his tall sons, fertile daughters, grandchildren. The paid mourners will pause for tuica and small bowls of ciorba[1] where they will hear more stories from visitors. The legends of his life will be rubbed into songs.

Absent from the music is the widow herself, dry-eyed near the door, greeting friends and family as she might on the day of her wedding to the man who made a ritual of beating her.

At the grove near the small creek, willows rustle their skirts. A priest with a long white beard and yellowing ponytail chants over the earth, the body, the coffin, the wooden leg. He pauses to bless the bread intended to feed the man on his voyage, one large loaf placed near his bald head, and seven smaller loaves laid around him, one for each day of the week. The mother tells her American daughter that, one week from now, another pomana (feast) will be held in his honor to refurbish his pantry. Three older men, his brothers, and one younger fellow shovel soil onto the coffin with care. They stand back and toss the soil towards the grove, guarding their shadows. If a shadow falls over the grove, death will find them.

The third way of seeing the caesura asks me to reflect on the story, and to imagine a time that is not mine, even though it exists in relation to me, in the fact of my having experienced it in Transylvania that summer where I met death for the first time.

To meet death is different from seeing it, being around it, or living with knowledge of its eventuality. I met many things that summer, in the year when my parents purchased tickets to Romania, the land of our birth, on the planet of not quite knowing what governments meant.

Decades after fleeing the dictatorship, my parents experienced this trip as a return to the familiar, or to the way in which they first knew themselves and the world. At fourteen, I didn’t remember (or know) my extended family, didn’t recognize the mountain valleys, the species of trees, the horse-drawn wagons filled with hay teetering along the dirt trails.

Surrounded by voices speaking my own language, for the first time in my life, I felt as if words could no longer hold the world I had been given. The uncanny rendered me inarticulate. My notebook was filled with new words, superstitions, melodic objects, and kitchen tools. I collected the names of towns as we rode trains through the Carpathians to arrive at the small wood house where my maternal grandmother took her final breath. The village is named Bran—home to the ghost of my mother’s mother, the one who died of breast cancer while she was pregnant with me, the namesake I never met.

In the village, events have their own time, punctuated by feasts, harvests, and the transhumance of sheep. What struck me was how all these things, and this changed notion of time, occurred in Romanian, a language shushed by the demands of American life. In the United States, it is important to be “legible” to others. Legibility enables humans to put each other in little boxes that don’t feel like threats. Like others, I didn’t notice those boxes until life exploded them. I didn’t notice how these boxes humiliated the humans set inside them until the world refused to be tamed, conquered, sorted, and labeled by my boxes.

Hearing the materials of everyday life named in Romanian, publicly, outside the house I shared with my parents and sister, changed what it meant to be human for me. The world that existed as a fantasyland cobbled together in photos and stories morphed into the context of living and being and seeing and tasting. To hear my own name pronounced in this language, intonated in the same way my parents said it (a way that did not resemble the sharp intonation of my name in the U.S.)—to hear this again and again, not just once, not just in whispers, made it possible for me to inhabit the multiple versions of self that no one spoke about over that ocean.

One of these selves was my namesake, the grandmother named Alina. I had to fly over an ocean for language to envelope me. I had to stand in Romania and disappear into the gratuitousness of being just another Alina. Not the only Alina or the only Eastern European girl, but one teen among others. Only then—only there—did words finally grow roots and come to life.

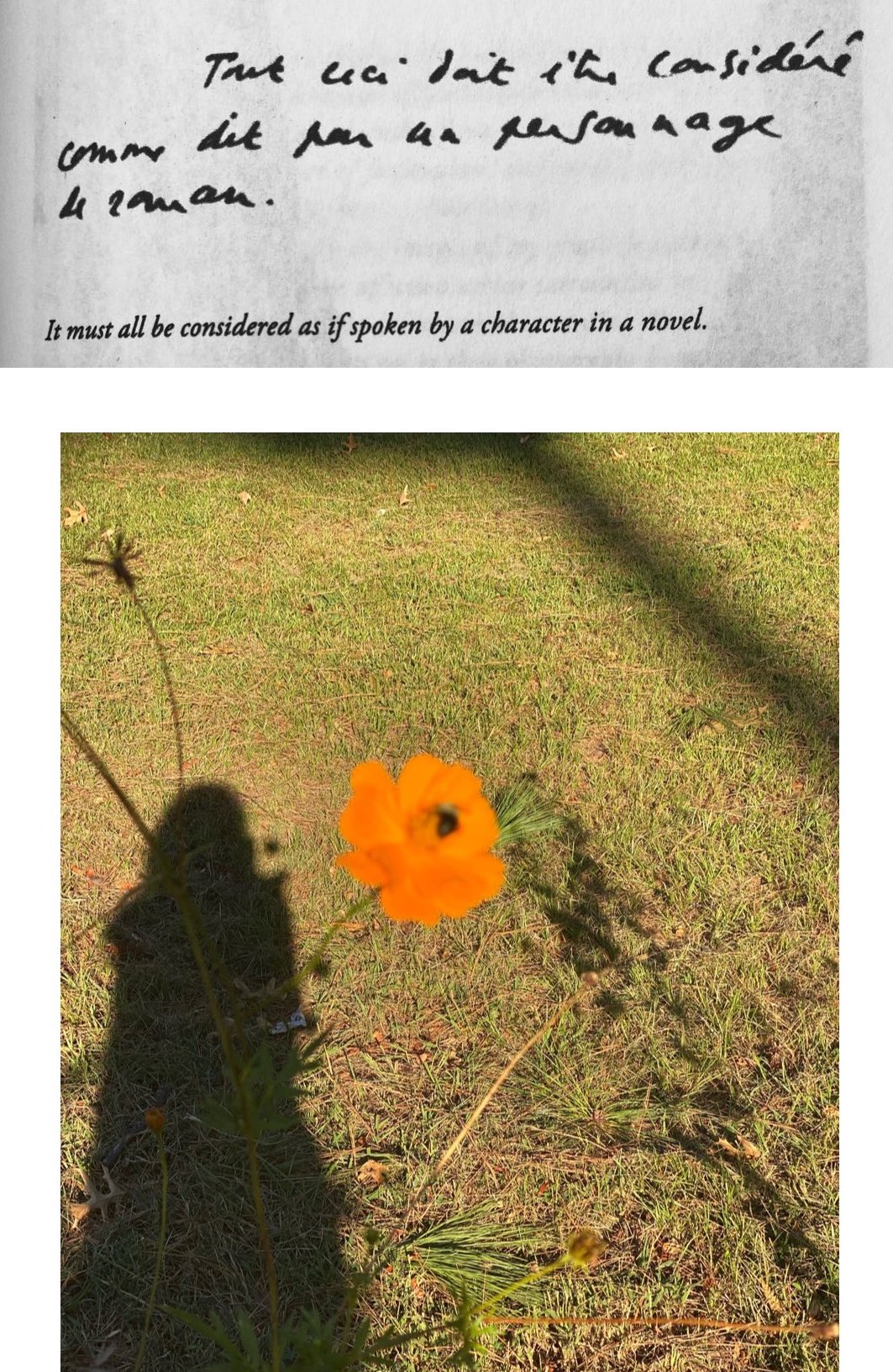

Collage created by author with quote from John Barthes.

Polish poet Adam Zagajewski called death “that connoisseur of form, that illustrious caesura,” offering us a sort of effusive silence carved by poetry. In this silence, I meet my namesake, the grandmother who died while my mother was pregnant with me, the final event before my parents fled their homeland, leaving me with my grandparents. Writing this space involves translating across borders, but the end will not be a translated body. Nor will it be a translated text. The body in translation demands fluidity as a form of existence, an ongoing reconciliation of subjects and verbs, a dialogue with ghosts in a land that stakes its claims on paper documents, in a superpower country that fashions its own exceptionalism from evidence rooted in visibility.

In an essay titled “The Aesthetics of Silence,” Susan Sontag insisted that “a landscape doesn’t demand from the spectator his understanding, his imputations of significance, his anxieties and sympathy; it demands rather, his absence, that he not add anything to it.” I disagree with her. A landscape exists in relation to the way the spectator sees it. The word “landscape” implies that a certain portion of physical terrain is being cut off from its entirety in order to be seen or described. The dictionary defines “landscape” as “all the visible features of an area of countryside or land, often considered in terms of their aesthetic appeal.” Even a desert landscape is brought to the page as an illustration of a particularly lonely and vast silence. In order to make this claim, Sontag has to pretend she can be a neutral observer of something created by the human gaze. I think neutrality is a fantastic temptation bequeathed to writers by science, and resisting this temptation is part of critical thinking, part of holding ourselves accountable for the words we bring to the world.

Critical neutrality is a particular kind of mask. Its authority is carved from a claim to access that Archimedian point. The relationship between closure and expectation results in predictability, that narrative urge to tidy things up. As humans, we want to link things—to link is to make sense—to forge a chain of events which reads like history and offers a sense of closure. Sense-making is critical to theory’s “metaphor compulsion,” which literary critic and theorist Svetlana Boym described as a tendency “to make significant and signifying all elements of everyday existence.”

“Metaphor compulsion” seeks a connection between, for example, the suicide of the poem’s speaker and the poet’s own death. But what would it mean to honor the difference between the text and the writer without assuming one at the mercy of the other?

Boym’s “performative criticism” emphasizes the interpenetration of different writing genres and different academic disciplines and discourses in order to look more closely at the “transgressive theatricality of lives and texts.” By “unlearning” its own methodology, performative criticism reveals the uncanny holes in literary discourse; it forces us to reckon with cultural contexts, and even to observe the particular mythography a critic brings to their studies of a poet.[2]

This sense-making urge is complicated by absence. And the complicated tends to haunt us. One of my favorite poets, Marina Tsvetaeva, exists for eternity in an unmarked, unknown grave. This sort of grave exists in the imaginary rather than the physical. Lacking a marker, Tsvetaeva’s absent memorial becomes what Boym called “an uncanny poetic monument that challenges living poets.” It serves as a memorial site and an erasure simultaneously.

The erased create a site where one meets in weirdness, in the unfinished, and the failure of ritual to consecrate and honor.

- Dear reader, I am setting the words that matter apart in italics. I am refusing their assimilation. No one in this country speaks Romanian. I won't cosplay coexistence or hybridity for you or Junot Diaz. ↵

- Unfortunately, Boym did not write a book specifically on neo-decadent poetics. This gap must be filled by others who read Boym and see the connections. When a writer dies, their X's roam the world, looking for another mind to imagine them. Boym's X's are very alluring to me. ↵