38 Translation.

Who is the author of Mugur? What is the director’s relationship to Cărbunariu’s play?

Did Ceausescu write the state pageants?

Who was the visionary of the moral hygiene regime of one-party rule in Romania?

I am missing something.

My partner agrees to watch Uppercase Print with me, if only to confirm that I am, indeed, missing something.

I tell him the title could also be translated “In Capital Letters” or “All Caps.”

Mugur’s crime was not just the content of his slogans but also the style he employed: he used dramatic and scandalous lettering; he wrote loudly. IN ALL CAPS. This turned up the volume of the utterance. Like screaming “FIRE!” inside a burning cinema.

Watching the film with an American differs from watching it alone. I find myself explaining the gaps, filling in the blanks, drawing connections he might not recognize without historical context.

The blurred white of the subtitle font makes the strangely translated parts poke out.

I correct and annotate the subtitular translations of Jude’s film until my partner asks me, politely, to stop.

He would prefer to watch the film without commentary.

“I can’t follow the subtitles and your captions at the same time,” he adds.

In an interview with Carmen Gray, Radu Jude said the only line he added to Carbunariu’s text was a reference to Cambridge Analytica, the company who stole Facebook data in order to undermine American elections.

“There is no reason to deal with history unless you can find something in it of the present time,” Jude continued. “If these problems had been closed, I wouldn’t make films about them.”

“Please stop translating over the captions,” my partner says.

He is reading the film as authored by the translator who gives us the captions. But I don’t agree with all of the translations. I want him to read the film the way I read it.

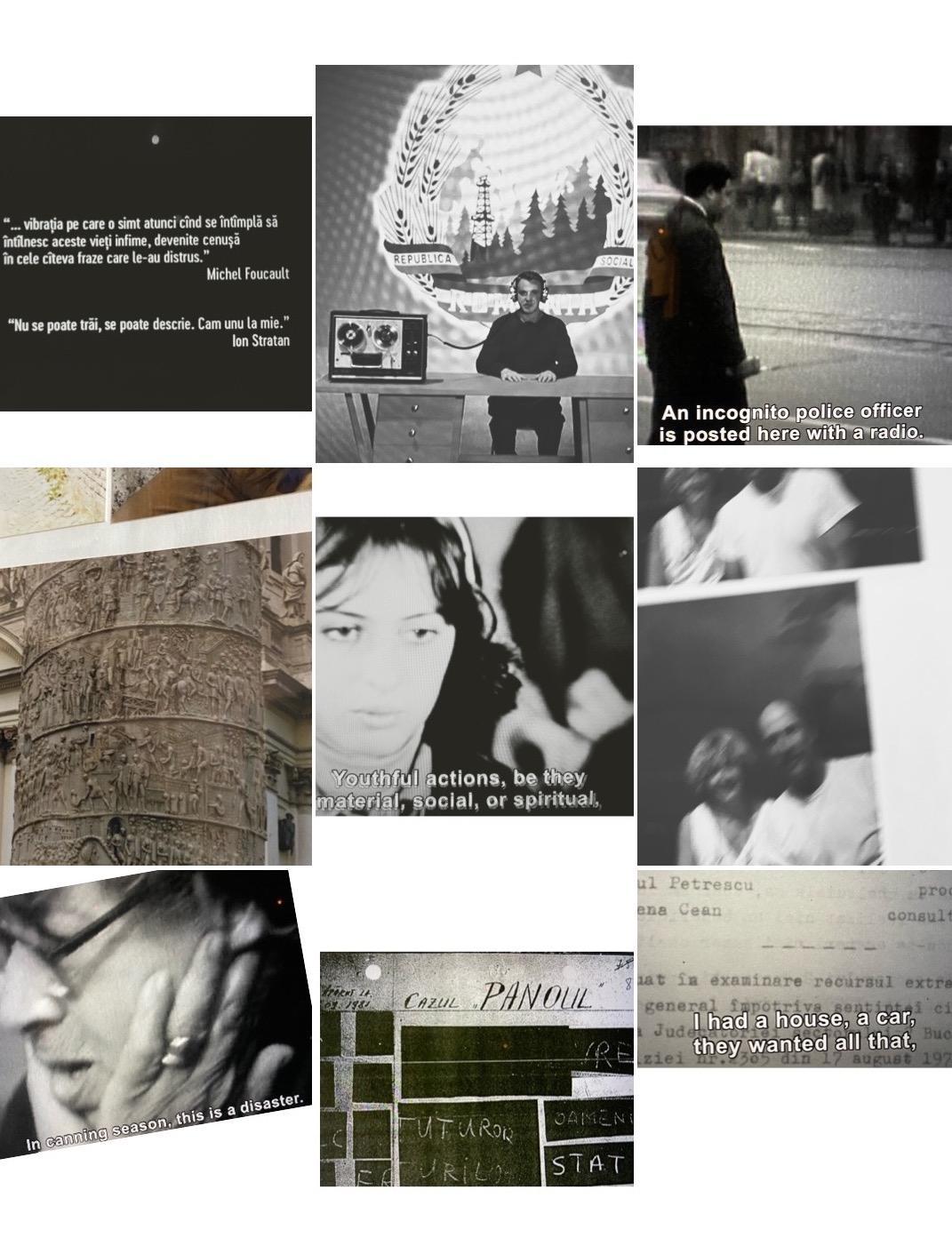

Collage including film stills from Radu Jude’s “Uppercase Print” (2020)

I continue reading the subtitles aloud—to hear the words translated into English, delivered in the flat affect of the apparatchiks’ intonation.

The deadpan delivery is contagious: it soaks the film, spreading from the dull matter-of-factness of the Securitate files into Mugur’s defense, into the language and tone dissidents used to defend themselves.

There is an absence of indignation in Mugur’s affect. The defendant cannot be furious, he cannot hire a lawyer, he cannot make a fuss or get his name in the papers or rely on a public petition. The brain is steeped in scarce-reality here: the population has internalized the master’s language.

Most dissidents were ordinary humans, not intellectuals, journalists, poets, or artists. The story of the artist dissident is more glamorous; it maps onto a trope we want to believe and to savor. It coincides with the heroism that U.S. artists and writers often imagine of themselves.

But Mugur was just a teenager, the son of a single mom who could barely manage work with the endless bread lines and economic poverty.

Mugur wasn’t a writer with a National Endowment of the Arts Fellowship.

Mugur wasn’t a member of a protest collective at an Ivy League school.

Mugur was nothing by every measure we use to valorize human activity. His resume was graffiti.

Mugur resists the aesthetics of heroism.[1]

- "Why do you refer to all the Romanians in this by first name?" my partner asks quietly. "I mean, why just the Romanians?" I go through this manuscript and change every instance I can find that is guilty of this. You are reading my corrected version. The X is the absence. ↵