20 This is the part about Walter Benjamin and the “golden cufflink.”

Following Walter Benjamin, I want to read the multiple registers of time across the films, texts, and stills for the “traces” where history becomes legible in the present as “co-incidence.” This coinciding implies a sort of recognition will occur: the familiar is recognized within the strange and the distant.[1] The temporal registers are blurred.

In Benjamin’s words:

Every present day is determined by the images that are synchronic with it: each “now” is the now of a particular recognizability. … It is not that what is past casts its light on what is present, or what is present its light on what is past; rather, image is that wherein what has been comes together in a flash with the now to form a constellation. In other words: image is dialectics at a standstill. For while the relation of the present to the past is purely temporal, the relation of what-has-been to the now is dialectical: not temporal in nature but figural . . .. The image that is read—which is to say, the image in the now of its recognizability—bears to the highest degree the imprint of the perilous critical moment on which all reading was founded.[2]

The golden cufflink, as a symbol, asks to be recognized as part of a certain professional, managerial class including hedge-fund managers, artistic patrons, and dictators. It gestures towards plenitude and power. When selling us national unity, politicians or corporate leaders create an iconography of what “We” are. This iconography tells a story that determines who is included, who is valued, and who is a threat to the group, as constructed by the image.

How do you want to be seen?

What will you do in order to be seen that way?

How does art engage the questions of visibility, recognition, and power?

Back in 2005, Florin Tudor curated an exhibit of Ceaușescu portraits titled “The Painting Museum.” The exhibit’s description gives the viewer a polyphonic iconography centering on the figure of the dictator:

Ranging from the picturesque to the sheer grotesque, this polymorphous portrait of Nicolae Ceaușescu introduces viewers to a biologic enigma. The subject seems unaffected by age, he actually grows younger, a process which culminates with a 1989 portrait of blossoming strength and youthful confidence. He is seen working on the country’s many construction sites, visiting factories or villages, in ‘permanent dialogue with the people’. He is the prototype of the ‘the new man’, which communist propaganda imposed as the fundamental aim of Romanian society.

Like a Hollywood icon, the prototype of “the new man” keeps getting younger and younger. Aesthetically, he has MILF-energy: he is coded to embody that particular, self-rejuvenating desirousness common to fantasies of eternal youth.

“The image that is read—which is to say, the image in the now of its recognizability—bears to the highest degree the imprint of the perilous critical moment on which all reading was founded.”

– Walter Benjamin

This painting is titled “Nicolae Ceaușescu and Scenes from the History of the People.”

According to the caption on the Romanian Cultural Institute’s website, the painting was offered to Ceaușescu by Natalia and Nicolae Gadonschi-Ţepeş on the occasion of his 54th birthday in January 1972. It represents the way the dictator wanted to be seen in that particular year. The images are the national heroes he claimed; the scythes represent the labor of the peasants and agricultural collectivization. The date, 1907, is sanctified in large red numbering. Electricity, hydroelectric dams, and other materials gather around the dictator like jewelry.

The dictator is a man who makes things happen. He produces events.

While visiting Maoist China with a group of fellow travelers, Susan Sontag tried to write about what she saw. (Sontag wasn’t a very good reader of China). Photos were used “to display what has already been described,” Sontag wrote, or to reinforce official dicta rather than reveal a new angle or perspective. The Chinese considered an image to be “correct” or “incorrect” based on its content and subject. A “corrected view” or corrected vision. To have seen wrong. The dissenting voice is a voice with vision problems.

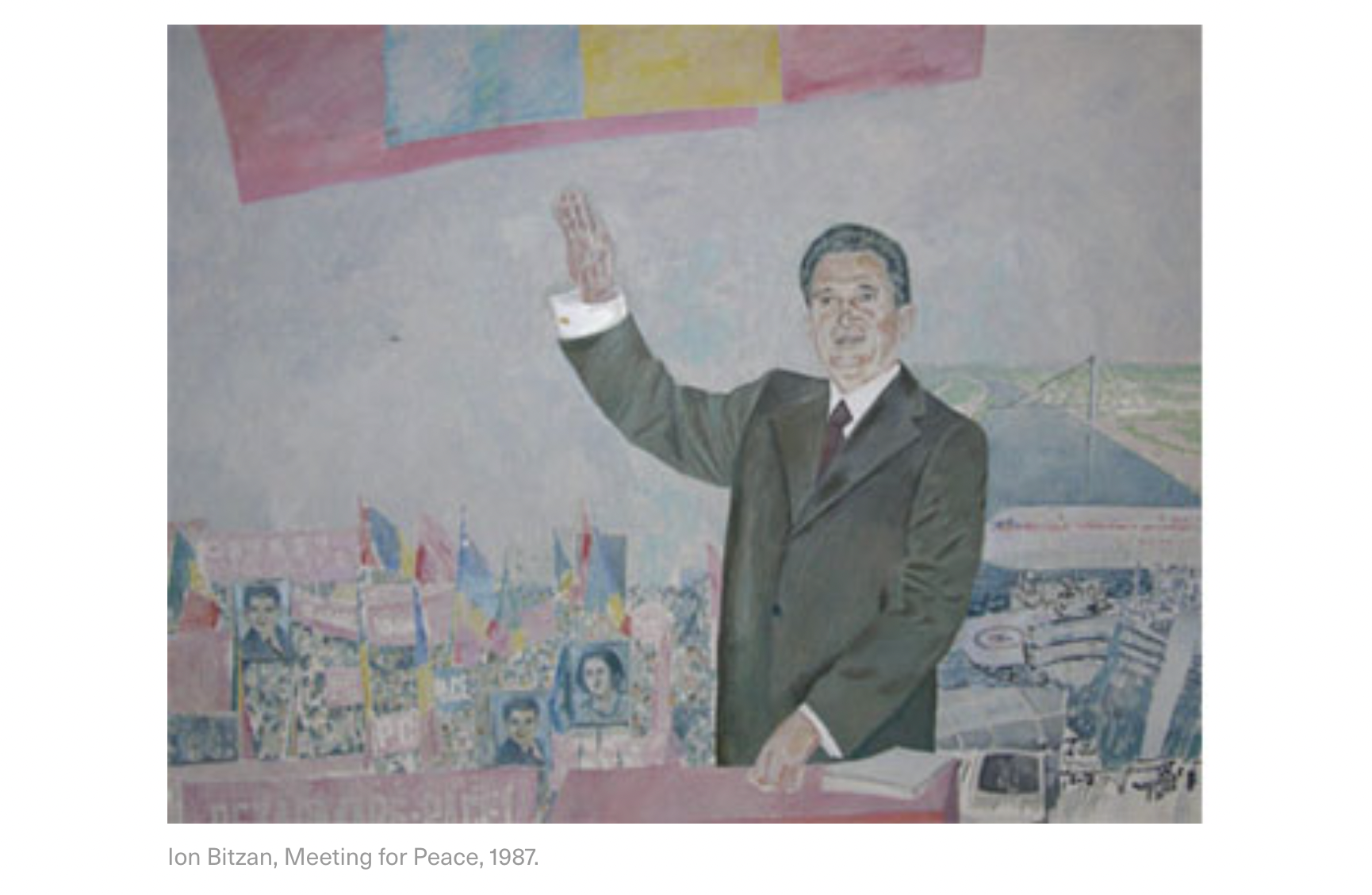

Ion Bitzan’s “Meeting for Peace” (1987) was featured in “The Painting Museum” exhibit. The golden cufflink snags the eye. The cufflink holds the bright white of the dictator’s shirt together, and this hand with the cufflink is then held aloft, above the heads of the sign-carrying masses.

Why does the golden cufflink occupy the center ground of the painting?

Maybe the cufflink exerts its centrifugal force in pacifying the other subjects. Only peace will reign beneath the dictator’s golden cuff. Only peace is permitted under the dictatorship. This is how the dictator communicates his orders to the people.

The caption for this photo reads: “Meeting on the ’23 August’ stadium in Bucharest, on the occasion of Romania’s National Day (August 23, 1986).”

What the caption doesn’t include is a translation of the words at the top of the stadium, positioned to radiate around the dictator’s image: Epoca de Aur. The dictator announces the era or epoch: his words automatically transcribe this era onto the bodies of the subjects as well as any legal descriptions of images.

Epoca de aur means “The Golden Age.” Those living in such plentitude have no possible reason to complain. The children of the golden age must testify to its goldenness. The historical context constructs the golden age as a repudiation of the recent past. In this case, Ceaușescu was repudiating the legacy of his predecessor, Gheorghe Gheorgiu-Dej, who led Romania through 1948 to 1959 in the relentless years of Stalinist indoctrination.

In the 1960s, the rise of Ceaușescu saw a shift in Communist Party discourse that embraced “nationalist communism.” Without abandoning the Stalinist hermeneutics of suspicion, the dictator’s nationalist communism articulated a critical stance on the Sovietization of Romania – and this stance included a flexibility away from socialist realism in the arts.

Inspired by his 1971 visit to North Korea, the dictator reoriented Romania towards youth indoctrination and isolation. Experimentalists were accused of decadence, obscurantism, subversive individualism, and other emotional crimes against the state.

The state had so many feelings.

The dictator felt for everyone.

Only the dictator knew how to feel correctly.

A podcast blows through the speaker behind me; a female poet refers to the ordinary warp and woof of things, an expression which unsettles me by pronouncing itself as an echo. I suspect echoes disconcert us by emphasizing the sound of something which could have passed as ordinary had we not listened to it, had we not paused to consider the words.

— What does it mean to be a “citizen”? What caesuras does citizenship demand in order to sustain itself?