24 This is the part about rhetoric.

Critic George Steiner defines rhetoric as “the craft of charging with significant effect the lexical and grammatical units of utterance.” As such, it exists in every form and mode of communication. Reading modifies, and is also modified by, “the communicative present of its object,” Steiner writes, in the context of arguing that context is always a dialectical arrangement. He suggests that each created object has its own “rhetoric of self-presentation.” Modernity’s concern with being understood or correctly interpreted is tightly bound up with the politics of visibility, and how one is seen. The image requires multiple modes of conveyance. But we can’t avoid analyzing how we look at ourselves when we write. We can’t avoid the “rhetoric of self-presentation” as we construct it.

Each artist sat alone in a room and determined how to relate to the dictator’s image. Each artist made a choice about how much creativity to exchange in return for vacations at the beach and education for their children. Each human does what they can in context.

Artist Ion Grigorescu has referred to Ceaușescu as a “kind of alter-ego” that inhabited his dreams for over twenty years. Even the mirror evoked the dictator; when Grigorescu peered into it, he saw his own resemblance to Nicu, the dictator’s favorite son.

How can we challenge the unspeakable hierarchies established by police states?

|

|

|

In March of 1978, as my father wandered through the Soviet Union and my mother prepared to give birth to me in Bucharest, Grigorescu filmed and developed a home experiment titled “Dialogue with Ceaușescu.”

The film could never be publicly shown. Grigorescu knew the risk of what he was doing. He used an 8mm standard camera and home laboratory to process the film.

There is only one actor in this film: Grigorescu plays all the parts. The artist is the singular star, the sole character, the dictator and the interviewer united in one body in this experimental dialogue with the Ceaușescu buried inside each Romanian citizen.

I slow down the film to take screenshots, to isolate images into “film stills.”

The script running over the faces of the two seated speakers is illegible.

“It is the artist and the dictator,” I tell myself.

The dialogue does not exist in words or sound—merely in Grigorescu’s screenshot of the television screen where the dialogue takes place.

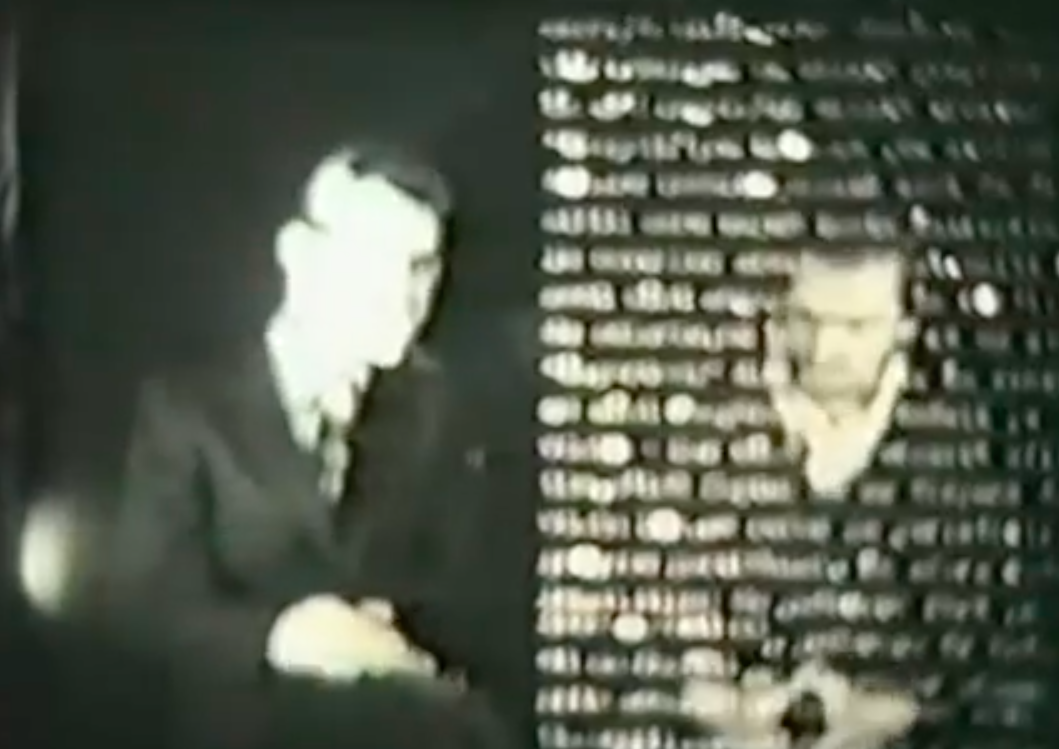

One can see the dictator’s mask is slipping here.

Or Grigorescu’s mask is slipping.

There is, again, this slippage…and then the blur reduces.

For a moment, the script seems almost legible. The dictator’s body turns towards the artist.

A sort of casual intimacy and tenderness is established in this flash of legibility—as if to say, these are real words.

The position of Ceaușescu’s hand resembles the first gesture in the sign of the cross which an Orthodox priest makes for absolution after one kisses his sleeve and the icon. It is part of every Romanian Orthodox Church service. I remember the taste of cologne on my tongue, my lips carrying the cologne from the priest’s hand to the face of Theotokos (or Virgin Mary) holding her son.

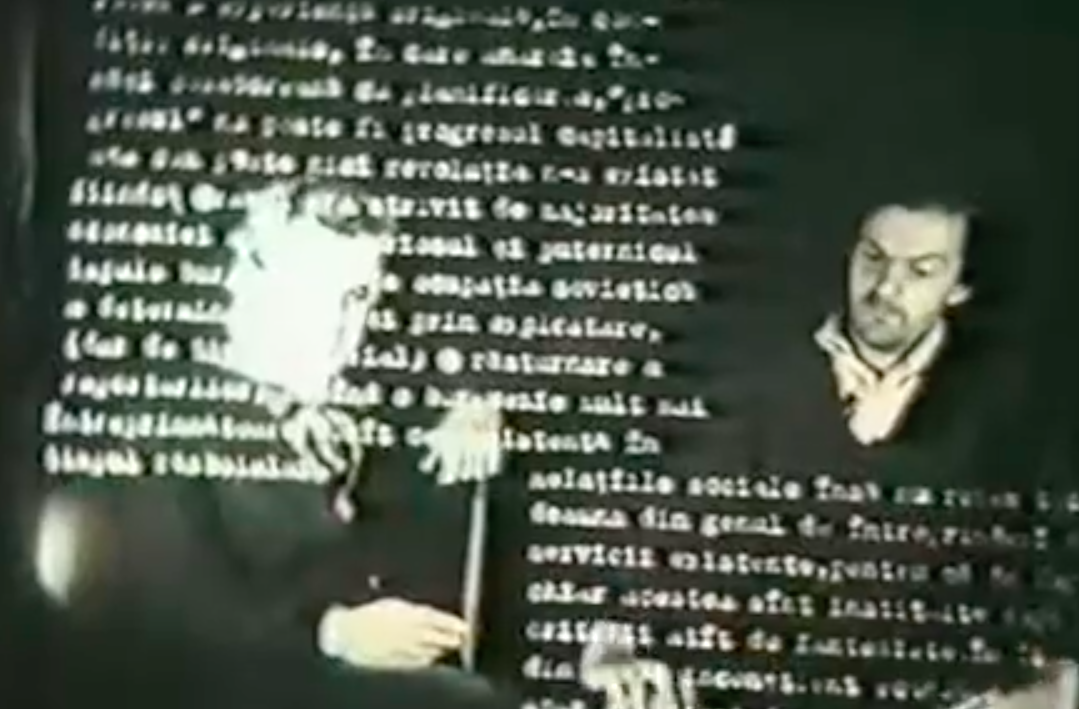

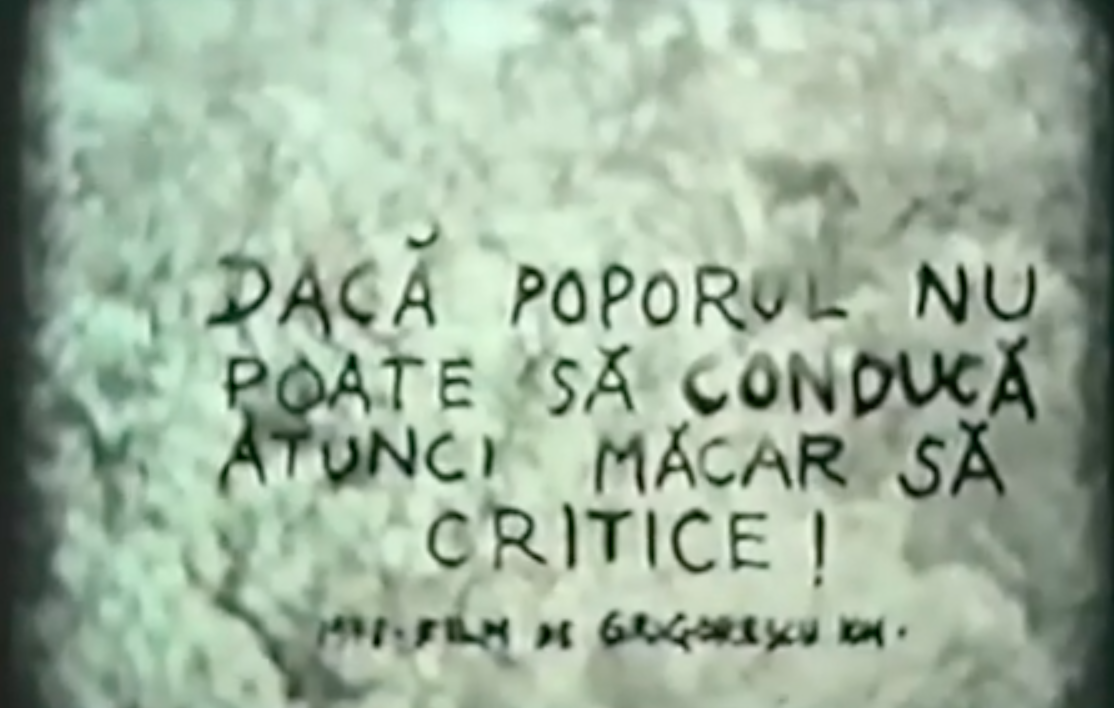

The speakers fade out, replaced by text in Grigorescu’s handwriting.

At this point, the silence of the film becomes unbearable.

But you can still see the dictator and the artist, the palimpsest beneath the handwritten words.

And the contrast between the illegible script and the handwritten words, which read: “If the People cannot lead here, they must at least critique!”

The dictator is the only artist with freedom of speech or expression. The dictator’s art is unlimited and unbounded. Birds which have seen the places where a god’s blood was spilled give more accurate omens. The perfect victim is easily made sacred.

Although socialist realism was relaxed after 1956 in the USSR and other Iron Bloc colonies, it remained the norm in Romania, gathering strength in the 1970s and 80s, particularly after Ceaușescu’s famous July speech, with its 17-point program to be followed by artists. The dictator’s Mangalia Theses (1983) defined art as an ideological tool which served the state and lacked autonomy of subject or method.