15 Here is a gap.

The interview form replicates the role my father’s testimony played in the trial that eventually enabled you to rejoin your family in the United States.

The surveillance files of the police state, the paranoia fueled by the Romanian dictatorship, and the silences in my own family carve themselves into the margins of my reading like cenotaphs. I can’t find a way to name what should be buried inside them. Nor can I figure out how to describe them. Yet I must move them out of the way in order to write clearly, to maintain the sort of vigorous[1] motion associated with critique.

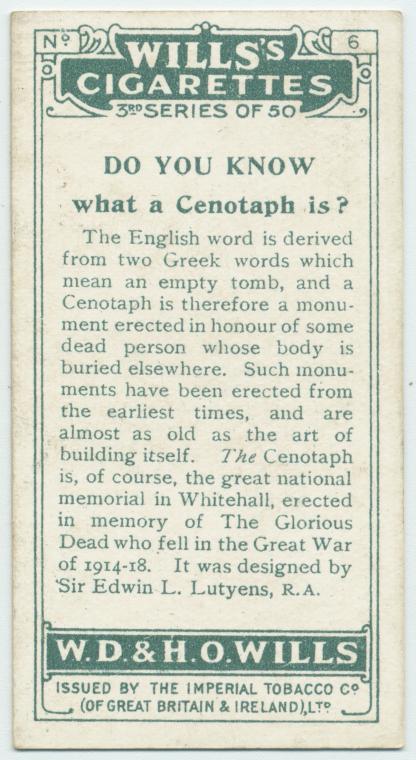

I don’t have a source for this image. I found it somewhere and saved it and now I’m not sure who to cite or attribute for its presence:

A cenotaph is a memorial to an absence. Because the tomb is empty, it resembles the tomb of the risen Jesus Christ—a space vacated by the death it inscribes.

Sometimes, I wonder if all the beings in cenotaphs were resurrected, or whether being resurrected is automatically implicated in existing as an unburied self. The writer cannot help unthinking the closure a cenotaph aims to secure.

Whenever the writer discovers a memorial, or an effort to provide evidence of closure, the unthoughts appear in the margins as silences, absences, and traces. The poet may attempt to evoke them through images and music. The critic may announce them by arguing with the invisible, unnamed interlocutors. Each writer engages the unthoughts in their own way. The only writer one should not trust is the one who seeks the sort of power that comes from ignoring the unthoughts.

I welcome the elliptical and the elusive as well as the graphics of mercilessness; there is no single style or avenue to the unthoughts.

Beware of the gatekeepers who insist that such rules of style exist. Remember, the gatekeeper’s job is to keep things as they are, to maintain the existing order and the aesthetic of not disturbing the cenotaph. The gatekeeper is paid to distract us from wondering where the unburied went, and why language insists on banishing it.

Do silences want libation? Does each silence need tipping?[2] Do I owe the silence an acknowledgment or a first drop in order to continue reviewing? If ghosts use silences to get our attention, then maybe talking about the silences enables the ghosts to feel seen.

“Surely what the ghosts want is visibility and recognition,” I thought to myself as I dialed my father’s phone number for relief.

- Vigor describes movement that is full of life. Rigor refers to the quality of being extremely thorough, exhaustive, or accurate. Rigor mortis is the full-of-no-lifeness which is death. ↵

- Tupac Shakur acknowledged the ancient ritual of libation, or leaving the first drops to honor a local deity, in his song, "Pour Out a Little Liquor." "Tipping" or "pouring one" is a tradition that has met me in Alabama, where friends sometimes poured one for peers who died young, as well as Romania, where we tipped the ground with plum brandy to placate family ghosts. ↵