47 Her favorite Leonard Cohen song.

The film still freezes time. The objective is three months pregnant with the child in the passport photo.

“Introducing the dimensions of time and movement into the act of watching stills is the foundation for the ethics of the spectator. This ethics is based on a series of assumptions: Photographs do not speak for themselves. Alone, they do not decipher a thing. Identifying what is seen does not excuse the spectator from “watching” the photograph, rather than looking at it, and from caring for its sense. And the sense of the photograph is subject to negotiation that unfailingly takes place vis-à-vis a single, stable, permanent image whose presence persists and demands that the spectators cast anchor in it whenever they seek to sail toward an abstraction that is detached from the visible and that then becomes its cliché.”

– Ariella Azoulay, The Civil Contract of Photography

The film still is a stopped frame, an image stolen from a context in which movement determines significance. Unlike photographs or portraits, film stills derive meaning from their relations with Film studies promoted films with large posters stylized in graphic design and rich representations intended to announce the film’s theme and attract viewers. Film stills, or stopped frames, were rarely used for posters. They weren’t compelling enough.

In 1990, my dad lugged a suitcase of white film reels back to the US. He had a projector. We watched these films by reel, the old way, projected on a blank wall.

Did something happen when he converted these reels to the digital images that permit stills? Was there a way to snap a still from reels?

A film is a roll of images that can be used by a projector to throw moving images on a screen or surface. Wood reminds me that films are “footage” involving movement, and this footage creates a sense of motion in the viewer. “Our relation to film as footage is a part of our relation to film as film,” he writes.

And our relation to film often coincides with the memory of events experienced in our lives.

Jacques Ranciere said every documentary should be asked what sort of fiction it is. Film tends to foreground the power of visual evidence–we see the thing and know what will happen ___ who is the criminal. “Seeing can’t be controverted, only contextualized, complemented by other stories.” (16) We feel as if we have witnessed something.

The family movie swallows me in its ever-present tense.

Scene: “The Bench Beneath the Tree“

I return to the video scene which takes place on the bench beneath the tree repeatedly, trying to isolate the subjects, or to make sense of each person separately. My mother, her father, and me.

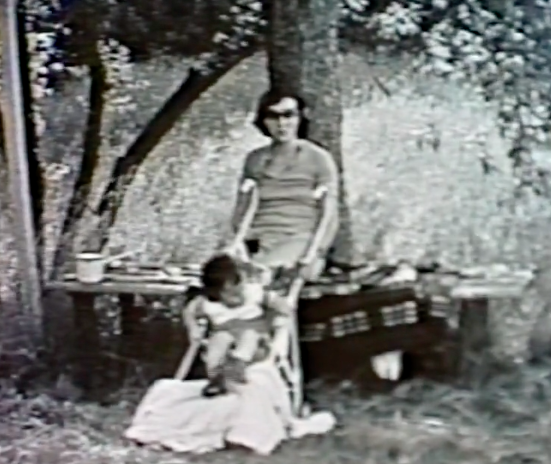

Still 1: Woman with baby on bench

Still 1 depicts a woman alone on the bench beneath a tree, her eyes shielded by large sunglasses, her head facing the camera, her back leaning against the trunk. A baby in a stroller, a white blanket at its feet. The woman is saying something to the camera. Or she is speaking to a figure just beyond the camera.

The video pans briefly to the field, then returns to the bench where a shirtless, middle-aged man sits next to the woman. The coffee pot sits between them. The woman is my mother. The bench is located behind her father’s house in Bran, a small mountain village in Transylvania. The man is her father. The two talk and drink Turkish coffee from clear kitchen glasses. Their lips move but the conversation is invisible to us, inaudible, buried inside the music.

My mother and her father share a cigarette as she rocks my stroller back-and-forth with her bare leg. Her legs are beautiful, astonishing, a soft counterpoint to the sobriety of her expression. She doesn’t smile. She rocks and sips from the cigarette as if it were a small vial. Her father smiles several times towards the camera. He radiates calm.

I am describing a still which I cannot share with you yet. But I can share a close-up of the bottom-half of this still.

Still 2: Baby near bench with blanket

Still 2 is a close-up of the two sitting on the bench and the baby at their feet. The man holding the camera is my father.

I am one year old, a wiggly new walker, squirming in the stroller, meeting the eye of his camera, as my mother jostles the stroller faster. He pans in on my face. We make eye contact—the child’s eye touches the father’s lens.

My parents will use these videos as mementos, or ways to recall me, when they are gone.

Most animals have a third eyelid which helps them hunt at night.

But I am not dead yet. I have no way of anticipating the morning when they will vanish.

In film and photography, an “aperture” is the space through which light passes in an optical or photographic instrument, particularly the variable opening by which light enters a camera.

Unlike Grigorescu’s home video experiments, the home videos my father developed in Romania avoid silence. Instead, each one is multiply-mapped according to the songs of my childhood. The songs in the videos are the same ones my father plays on weekends, when he sits on the porch and talks to my mother.

Listening to Maria Tanase’s “Ciuleandra,” I am struck by the extraordinary care and tenderness with which my father assembled these films and developed these reels in order to carve moments from motion and time, moments lit with the aura of those last days.

The uncut hay feathers the horizon. The hay positions itself as a relic, an arabesque that no longer exists in the heavily-touristed village of Bran, where this video takes place.

The human subjects are indeterminate figures who exist in relation to looking for, or looking towards, one another.

Still 3: Gheorghe under the tree

Still 3 is a close-up of my grandfather, Gheorghe Gancevici, sitting on the bench. My mother sits next to him; the infant sits in the lower half of the screen between them. I want to look at him, to imagine him alone at the house he built for his dead wife, Alina.

Several times in the video, both Gheorghe and his daughter look for Alina. She is not There. She died in this house a little over a year ago.

The child, the makeshift Alina, plays with a neighbor wearing a dress near the white car.

“Absolute silence: a choking sound.” This is how my aunt described Gheorghe’s response to the phone call she made from the hospital, telling him “Alina has been born.”

Silence that hisses and crackles over the phone line. Silence that takes up space.

Scene: “The Child Playing with Dirt Near the Car”

The word aperture comes from the Latin word apertura, where “apert-” means ‘opened’ and “aperire” means ‘to open’.

An aperture is a hole or a gap. A gap is one letter shy of a gape. A gape is one space away from being agape.

The problem is that a hole makes me feel responsible for filling it.

I lift words as if they were tiny shovels and carry dirt towards the gape in the ground. I am so desperate to hide the hole—decades of filling the hole—years of not understanding that the hole should be taken for an aperture instead. Since I cannot find my way into this review, I decide to look through the opening.

This scene, “The Child Playing with Dirt Near the Car,” runs for the remainder of the Maria Tanase song.

The camera follows the child through a sequence of repetitive actions which revolve around picking up chunks of dirt, standing, and then watching it slip through her fingers. It is located up the hill from the bench. The camera must be standing near the house, looking at the space around the car parked to the left of the main entrance.

I loop it for a few hours, pausing occasionally to screenshot a still.

Still 1: Child looking at empty hands.

In Still 1, the infant squats and stares at her empty hands. She picks up the dirt and watches it fall from her hands, again and again. Her eyebrows are furrowed in puzzlement. Is this the first time she has played with dirt?

I use the pronoun she even though this child is hardly feminine, not yet defined by her gender. The child does not know itself as her quite yet. Nothing about the child immediately designates “her,” since no one in the video speaks, and no one addresses the child as “her.”

The camera is very close. In drawing so close to the child, the camera sets the child apart from the landscape.

Still 2: Child raising empty hands.

In Still 2, we see the child raising her empty hands after just having spilled all the dirt in them. If she expresses this in language, it remains unknown to us.

Only her face and actions are legible.

(Its face—again, the child could be any gender.)[1]

When I text this image to my father and ask what I was doing in it, my father says: “Oh, you wanted me to pick you up.”

He is the one who was holding the camera.

—And yet, nothing in the video suggests the infant wants the cameraman to pick her up. Immediately after raising her hands, she squats again and lifts more dirt into her pudgy hands.

The child in the image ‘wants to be picked up’, but the child in the video is very busy and fascinated in the activity called ‘playing with dirt’.

At one point, the child stands up with dust clenched in her fists and looks at the camera before checking her hands.

Still 3: Child looking at camera just before checking her hands.

The film slows down here, at Still 3.

The background music drags its violins over the child’s furrowed eyebrows.

I read somewhere that dust could be a metonym for the essence of the archive, or that which is filed away and forgotten. The proper disposal of dust and ash absolves the living. The archive gestures towards its own resolution, or to the way in which its contents allow us to close the filing cabinet. There is a necrophiliac edge to lyric poetry.

Derrida’s hauntology has us haunted by events that never actually happened—dreams which didn’t fruit, futures that stayed abstracted without turning into reality or life.

These events occurred in the lives of others, in their books, their music, their words. When Burial tells Mark Fisher that he remembers leaving the city to hang out along the British seashore with his friends, to stroll those sands and stones in absolute darkness, to wander together holding hands and using a lighter to discern their next steps, to watch as a friend lifts the light to see where you were “and the image of where you’ve just been would still be on your retina.”

To be distracted by the possibility of the retina as another medium for the poetics of quotation. To wonder at the extent to which darkness, itself, provides an entryway into art. Darkness, who offers us the instruments for the poetics of quotation. Darkness, the primordial oozing.

It is in the darkness that we find and use the lighter.

To pitch the bassline dark enough to need a lighter.

- But she is me, I want to say. There are ways in which I cannot read this neutrally. ↵