43 Hauntology of boxing.

One reads the still present in stills from a short film by Ion Grigorescu titled “Boxing” (1977).

During the 1970’s, as Ceaușescu’s regime rode Romanians towards starvation, Grigorescu used his own body to probe the distance between performance and recorded image by staging a series of intimate experiments secretly in his apartment. He created the film alone, and this solitude, this extraordinary confinement, is palpable in the way the subject slips between a character and a self-portrait.

The only sound is a brief crackling at the beginning. In black and white, a naked man boxes in a small studio with a shadow of himself.

Divided into three one-minute boxing rounds, the film borrows this convention from the sport of boxing. Grigorescu made it by first exposing the film as he boxed in one direction, then again as he boxed the other.

A game keeps score. A boxing match sets itself up as a game which can be won or lost.

Is “Boxing” a game? Is a game always a performance?

How does the performance of a game implicate players differently from the performance of an image?

Is the artist struggling with an image of himself or an alter ego?

I assume the alter ego is the boxer on the left because he is slightly less dense and shadowy than the boxer on the right. The boxer on the left fades with each round. By the final round, he resembles a sheer shadow. But it is then—when he is least visible—that the boxer on the left seems stronger and wins the match.

How does time sign its value in this film—or in these stills?

“A stopped frame outside of a movie isn’t anything, not even a photograph,” Michael Wood wrote in Film: A Very Short Introduction.

Film stills are only ‘something’ in the context of a film “projected at the right speed, 24 frames per second.” This is the speed of projection, but the speed hides a particular darkness, as Mary Ann Doane notes, since “during the projection of a film, the spectator is sitting in an unperceived darkness for almost 40% of the running time.” The film projection’s speed keeps us from perceiving the “lost time represented by the division between frames.”

The stills emphasize certain moments by pausing time, stopping the flow of images, turning the instants into one “instance,” a reified image that makes an “event” from what is removed. In this, the still (or screenshot) resembles the use of textual quotation.[1]

Digital archives and collections reference Grigorescu’s film as a piece produced in 1977.

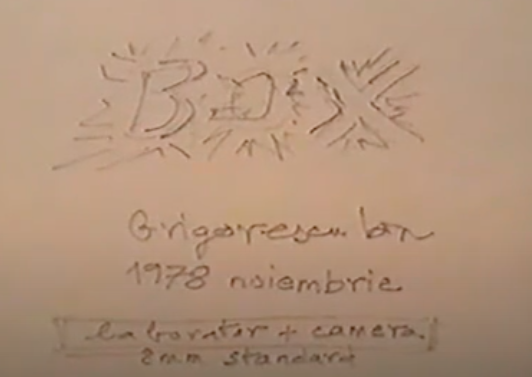

While viewing the credits, I pause for closer look and snap a screenshot:

The screenshot announces this as Grigorescu’s “Box” (not “Boxing”), which he made with film lab and an 8mm standard camera in November 1978.

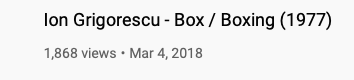

To confirm my own confusion, I also took a photo of the film’s title and presentation on YouTube:

The time stamp for Grigorescu’s film seems to also be plagued by a shadow or shadowed by a year and a title.

I’m not sure if 1977 or 1978 is the alter ego. Or what winning this match would mean for time.

Am I in a box, or am I boxing?

- Michael Wood. Film: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press: London, 2012 ↵