37 Collaborative authorship.

By 1965, 7 million Romanians (or one-third of the adult population) appeared in the Securitate registers. The illusion of complete surveillance was internalized as a mindset: Romanians displayed (and some would argue, still display) continuous, amorphous fear and suspicion of the other. By the 1980s, this suspicion had become the norm, “this awareness of being followed”. The culture of paranoia was still frothing in 1989, when Securitate had around 450,000 citizens working as informers.

Like George W. Bush’s use of “collateral damage” to describe civilian deaths in Iraq, Securitate had a discursive regime that would have thrilled Michel Foucault. “Reforming the objective” was code for active measures to repress political dissidents. “Protection of youth” was the code to indicate the need for surveillance.

As I amass folders of screenshots and fragmented images from the film, it becomes impossible to establish their chronological sequence. The end of a smile resembles the beginning of a smirk. The skid in a conversation often pans away from it, and the relationship between the skid and the pan is random, unpredictable, clipped. Three folders filled with stills on my laptop.

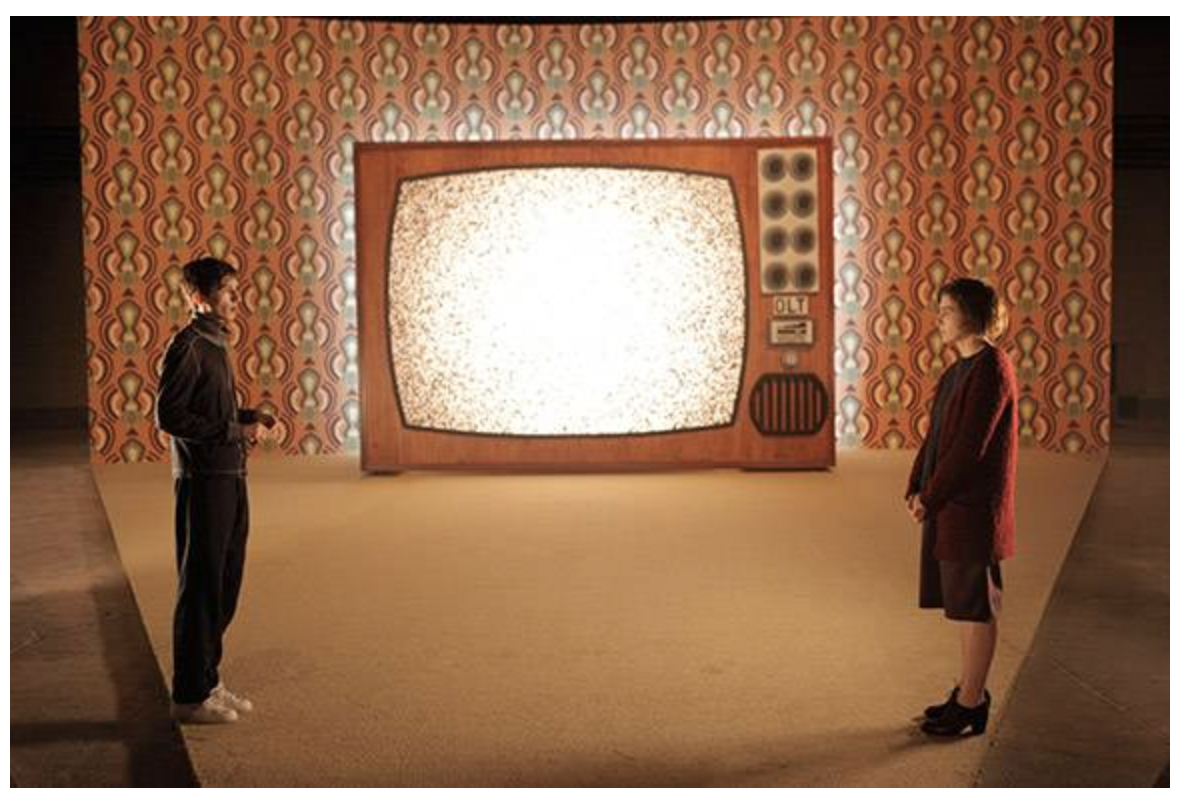

Photo by Silviu Ghetie.

What director Radu Jude called “this dialectical montage” speaks to the use of quotation and dictator-nostalgia in former Eastern bloc countries.

“If the regime showed any self-criticism at all, it was to tell the population that if there was a problem, they would solve it, but of course they only chose small problems, like a broken park bench,” Jude told an interviewer. “It was an insidious way to show social control, because, of course, the real problems were completely different.”

Carmen Bugan’s father was dangerous.

“My father spent a total of twelve years in the worst Romanian prisons and forced labor camps because he praised the democratic values of the West…I ask myself: was he really that dangerous?” The typewriter was used to create and distribute pamphlets; Bugan requests a copy of her family’s Secruitate files while working on the memoir, but she doesn’t get to see these criminal pamphlets until 2011, when she goes to Romania.

There, in her father’s file, Bugan finds a sheet of paper typed in 1981, calling for a general strike until the following demands are met: a five-day work week, freedom to form labor syndicates, returning of land to peasants, permission to start small businesses, permission to travel abroad for pleasure or work, the freeing of all political dissidents, improvement of infrastructure and food transportation to rural villages and remote towns, and better pension plans.

I keep repeating myself. Repetition is a strategy that aims for recognition: some part of me believes that truth can be recognized in text. But representation’s claims are contingent. In his 1970 essay, “The Third Meaning,” Roland Barthes insists that a film still is not a “sample” because it cannot represent the film. The film still is “a quotation… the fragment of a second text whose existence never exceeds the fragment.”

Reviewing my stills from Jude’s film, it seems that context gets mispronounced or awkwardly conjugated when the fragment is removed from a text and read separately. Like when someone calls out your name from the front of the classroom but says it wrong or mispronounces it so badly that you cannot recognize yourself inside it.

By permitting instantaneous and vertical reading, film-stills refuse linear time and chronology. In lieu of a story, what emerges is an iconography. I find myself quoting the folk singer from Ceausescu’s television programming that Radu Jude quotes in the film in a quotation of a quotation. This layered relationality to time and space in the he-said, they-said, she-said, we-said, blurs the distance between the speech act and the citation.

Barthes, nodding: “this still offers us the inside of the fragment.”