39 “To exist in English.”

“I don’t think you are reading this correctly,” I tell my partner.

“You keep saying that,” he says. “But how do you even know? How do you know how I’m reading this without bothering to ask?”

My desire to rule the translation is tyrannical.

I, too, have a caesura problem.

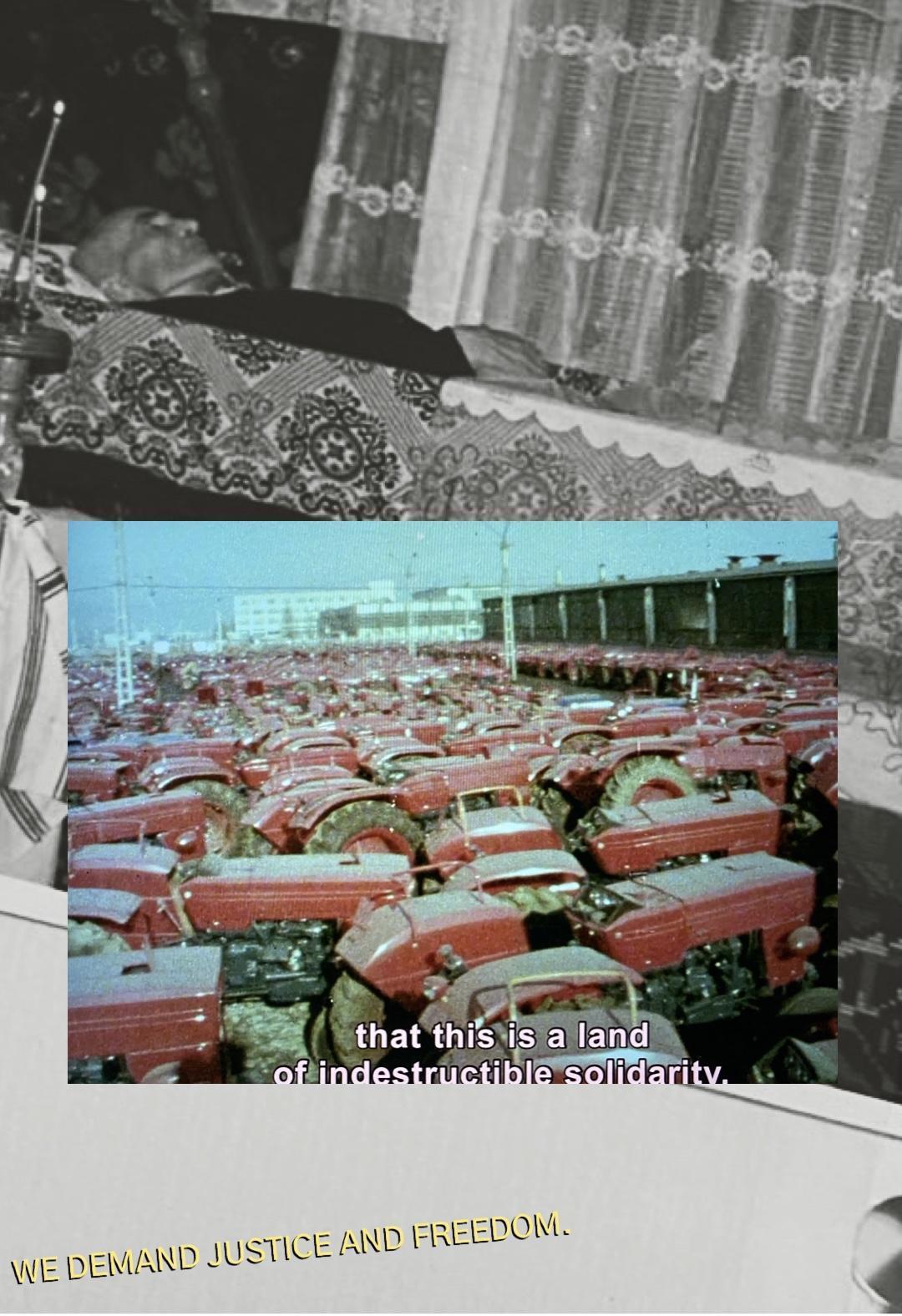

The director’s decision to interrupt various police interrogations with the folky socialist empowerment-uplift of Ceaușescu’s TV commentary cannot remind non-Romanians of anything except pure, pleasurable kitsch. There is no context in which those television programs can be familiar to them. The caesura has a different effect when the only relevant stickiness is impersonal. In such cases, what sticks is the stereotype. The Balkanismo. The Slav. The Eastern European.

Although there is no association for those who lived in the west, the unknowing audience can probably sense the “nostalgia program” effect as a soporific, a soother, a positivity hymn against the despair and pessimism of the surveilled society. But I can’t speak for my partner without inventing him.

In dialogue with Emil Cioran’s ghost, Carmen Bugan invokes his warning from The Temptation to Exist that adopting the language of the other is an act of self-betrayal that tears the writer from his memories. “He who turns against his language, adopting that of others, changes his identity and even his deceptions,” Cioran wrote a few years before officially adopting French as his writing language. Yet Cioran continued corresponding with family and friends in Romanian, which is to say, his public discourse continued in the language rendered private by exile.

Accepting this “temptation to exist in English,” Bugan responds to Cioran a poem, “The House Founded on Elsewhere”:

Not all the words you say are the Self and not all turning

Against your language is self-betrayal. Behind each word

Is what tries to get inside it. That is what matters

Whether I speak it in my own language

Or in the tongue of others. The thought, the breath,

With which you send out love, or forgiveness, say

Outlive the word and languages, outstrip

The syllables at prayer or play.

The poet exists in the nostalgia of having-being-known as well as the life built between languages. As counterpoint to Cioran’s self-mythologizing singularity, Bugan poses Hungarian poet George Szirtes’ view that a poet must assume he exists in the rootless, free-ranging “internationalism” which is “the lifeblood of art.” Writing in both English and Hungarian, Szrites expresses the view of many translators, or the experience of those who dedicate their lives to bringing words across borders and discovering, often, how being human translates into a common terrain.

In seeking what is common to humankind, Szirtes refuses to police boundaries and borders. A border-leaper rather than border-keeper, Szirtes takes the poem as a palimpsest, a form noted for its evocations of rootlessness and multivalence. Writing from Cluj, he recalls the oppression of having his language forbidden by nationalist Romanian leaders—even as he recalls his mother’s hostility to Hungarian Jews. “I don’t want to be certain of anything,” Szirtes says of his mother’s relationship to historical upheaval, “I don’t want to come to conclusions.”

Collage of screenshots from Jude’s film.