7 Chapter 7. Knowledge

CHAPTER 7: KNOWLEDGE

People form mental concepts of categories of objects, which permit them to respond appropriately to new objects they encounter. Most concepts cannot be strictly defined but are organized around the “best” examples or prototypes, which have the properties most common in the category. Objects fall into many different categories, but there is usually a most salient one, called the basic-level category, which is at an intermediate level of specificity (e.g., chairs, rather than furniture or desk chairs). Concepts are closely related to our knowledge of the world, and people can more easily learn concepts that are consistent with their knowledge. Theories of concepts argue either that people learn a summary description of a whole category or else that they learn exemplars of the category.

CHA[TER 7 LICENSE AND ATTRIBUTION

Introduction through Theories of Concept Representation

Source: Murphy, G. (2019). Categories and concepts. In R. Biswas- Diener & E. Diener (Eds), Noba textbook series: Psychology. Champaign, IL: DEF publishers. Retrieved from http://noba.to/6vu4cpkt

Categories and Concepts by Gregory Murphy is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Condensed from original version.

Concept Organization

Source: Multiple authors. Memory. In Cognitive Psychology and Cognitive Neuroscience. Wikibooks. Retrieved from https:// en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Cognitive_Psychology_and_Cognitive_Neuroscience

Wikibooks are licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution- ShareAlike License.

Cognitive Psychology and Cognitive Neuroscience is licensed under the GNU Free Documentation License.

Condensed from original version. American spellings used. Content added or changed to reflect American perspective and references. Context and transitions added throughout. Substantially edited, adapted, and (in some parts) rewritten for clarity and course relevance.

Cover photo by Alli Elder on Unsplash.

Although you’ve (probably) never seen this particular truck before, you know a lot about it because of the knowledge you’ve accumulated in the past about the features in the category of trucks. [Image: CC0 Public Domain, https://goo.gl/m25gce]

Consider the following set of objects: some dust, papers, a computer monitor, two pens, a cup, and an orange. What do these things have in common? Only that they all happen to be on my desk as I write this. This set of things can be considered a category, a set of objects that can be treated as equivalent in some way. But, most of our categories seem much more informative—they share many properties. For example, consider the following categories: trucks, wireless devices, weddings, psychopaths, and trout. Although the objects in a given category are different from one another, they have many commonalities. When you know something is a truck, you know quite a bit about it. The psychology of categories concerns how people learn, remember, and use informative categories such as trucks or psychopaths.

The mental representations we form of categories are called concepts. There is a category of trucks in the world, and I also have a concept of trucks in my head. We assume that people’s concepts correspond more or less closely to the actual category, but it can be useful to distinguish the two, as when someone’s concept is not really correct.

Concepts are at the core of intelligent behavior. We expect people to be able to know what to do in new situations and when confronting new objects. If you go into a new classroom and see chairs, a blackboard, a projector, and a screen, you know what these things are and how they will be used. You’ll sit on one of the chairs and expect the instructor to write on the blackboard or project something onto the screen. You do this even if you have never seen any of these particular objects before, because you have concepts of classrooms, chairs, projectors, and so forth, that tell you what they are and what you’re supposed to do with them. Furthermore, if someone tells you a new fact about the projector—for example, that it has a halogen bulb— you are likely to extend this fact to other projectors you encounter. In short, concepts allow you to extend what you have learned about a limited number of objects to a potentially infinite set of entities.

You know thousands of categories, most of which you have learned without careful study or instruction. Although this accomplishment may seem simple, we know that it isn’t, because it is difficult to program computers to solve such intellectual tasks. If you teach a learning program that a robin, a swallow, and a duck are all birds, it may not recognize a cardinal or peacock as a bird. As we’ll shortly see, the problem is that objects in categories are often surprisingly diverse. Simpler organisms, such as animals and human infants, also have concepts (Mareschal, Quinn, & Lea, 2010). Squirrels may have a concept of predators, for example, that is specific to their own lives and experiences. However, animals likely have many fewer concepts and cannot understand complex concepts such as mortgages or musical instruments.

NATURE OF CATEGORIES

Traditionally, it has been assumed that categories are well-defined. This means that you can give a definition that specifies what is in and out of the category. Such a definition has two parts.

First, it provides the necessary features for category membership: What must objects have in order to be in it? Second, those features must be jointly sufficient for membership: If an object has those features, then it is in the category. For example, if I defined a dog as a four-legged animal that barks, this would mean that every dog is four-legged, an animal, and barks, and also that anything that has all those properties is a dog.

Unfortunately, it has not been possible to find definitions for many familiar categories. Definitions are neat and clear-cut; the world is messy and often unclear. For example, consider our definition of dogs. In reality, not all dogs have four legs; not all dogs bark. I knew a dog that lost her bark with age (this was an improvement); no one doubted that she was still a dog. It is often possible to find some necessary features (e.g., all dogs have blood and breathe), but these features are generally not sufficient to determine category membership (you also have blood and breathe but are not a dog).

Even in domains where one might expect to find clear-cut definitions, such as science and law, there are often problems. For example, many people were upset when Pluto was downgraded from its status as a planet to a dwarf planet in 2006. Upset turned to outrage when they discovered that there was no hard- and-fast definition of planethood: “Aren’t these astronomers scientists? Can’t they make a simple definition?” In fact, they couldn’t. After an astronomical organization tried to make a definition for planets, a number of astronomers complained that it might not include accepted planets such as Neptune and refused to use it. If everything looked like our Earth, our moon, and our sun, it would be easy to give definitions of planets, moons, and stars, but the universe has sadly not conformed to this ideal.

Here is a very good dog, but one that does not fit perfectly into a well-defined category where all dogs have four legs. [Image: State Farm, https://goo.gl/KHtu6N, CC BY 2.0, https://goo.gl/BRvSA7]

TYPICALITY

Even among items that clearly are in a category, some seem to be “better” members than others (Rosch, 1973). Among birds, for example, robins and sparrows are very typical. In contrast, ostriches and penguins are very atypical (meaning not typical). If someone says, “There’s a bird in my yard,” the image you have will be of a smallish passerine bird such as a robin, not an eagle or hummingbird or turkey.

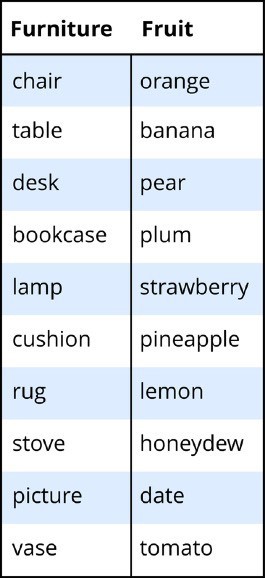

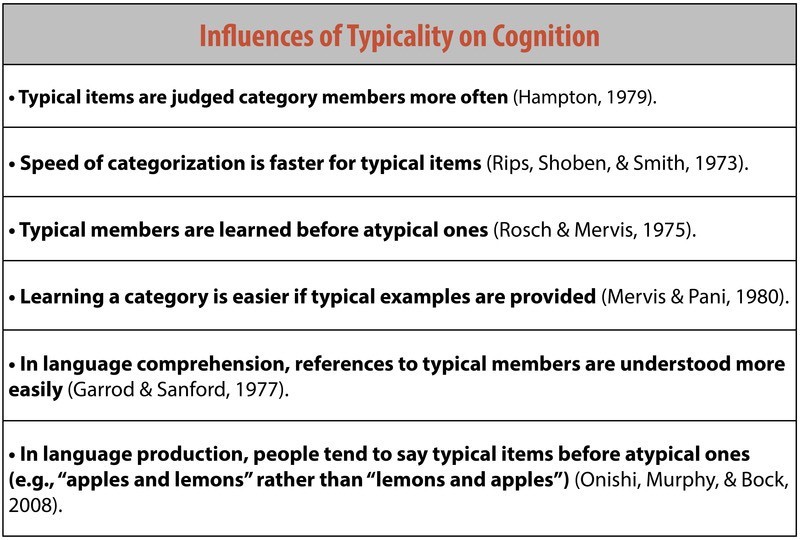

You can find out which category members are typical merely by asking people. Table 1 shows a list of category members in order of their rated typicality. Typicality is perhaps the most important variable in predicting how people interact with categories. The following text box is a partial list of what typicality influences.

We can understand the two phenomena of borderline members and typicality as two sides of the same coin. Think of the most typical category member: This is often called the category prototype. Items that are less and less similar to the prototype become less and less typical. At some point, these less typical items become so atypical that you start to doubt whether they are in the category at all. Is a rug really an example of furniture? It’s in the home like chairs and tables, but it’s also different from most furniture in its structure and use. From day to day, you might change your mind as to whether this atypical example is in or out of the category. So, changes in typicality ultimately lead to borderline members.

Table 1. Examples of two categories, with members ordered by typicality (from Rosch & Mervis, 1975)

SOURCE OF TYPICALITY

Intuitively, it is not surprising that robins are better examples of birds than penguins are, or that a table is a more typical kind of furniture than is a rug. But given that robins and penguins are known to be birds, why should one be more typical than the other? One possible answer is the frequency with which we encounter the object: We see a lot more robins than penguins, so they must be more typical. Frequency does have some effect, but it is actually not the most important variable (Rosch, Simpson, & Miller, 1976). For example, I see both rugs and tables every single day, but one of them is much more typical as furniture than the other.

Text Box 1

The best account of what makes something typical comes from Rosch and Mervis’s (1975) family resemblance theory. They proposed that items are likely to be typical if they (a) have the features that are frequent in the category and (b) do not have features frequent in other categories. Let’s compare two extremes, robins and penguins. Robins are small flying birds that sing, live in nests in trees, migrate in winter, hop around on your lawn, and so on. Most of these properties are found in many other birds. In contrast, penguins do not fly, do not sing, do not live in nests or in trees, do not hop around on your lawn. Furthermore, they have properties that are common in other categories, such as swimming expertly and having wings that look and act like fins. These properties are more often found in fish than in birds.

According to Rosch and Mervis, then, it is not because a robin is a very common bird that makes it typical. Rather, it is because the robin has the shape, size, body parts, and behaviors that are very common among birds— and not common among fish, mammals, bugs, and so forth.

In a classic experiment, Rosch and Mervis (1975) made up two new categories, with arbitrary features. Subjects viewed example after example and had to learn which example was in which category. Rosch and Mervis constructed some items that had features that were common in the category and other items that had features less common in the category. The subjects learned the first type of item before they learned the second type. Furthermore, they then rated the items with common features as more typical. In another experiment, Rosch and Mervis constructed items that differed in how many features were shared with a different category. The more features were shared, the longer it took subjects to learn which category the item was in. These experiments, and many later studies, support both parts of the family resemblance theory.

When you think of “bird,” how closely does the robin resemble your general figure? [Image: CC0 Public Domain, https:// goo.gl/m25gce]

THEORIES OF CONCEPT REPRESENTATION

Now that we know these facts about the psychology of concepts, the question arises of how concepts are mentally represented. There have been two main answers. The first, somewhat confusingly called the prototype theory suggests that people have a summary representation of the category, a mental description that is meant to apply to the category as a whole. (The significance of summary will become apparent when the next theory is described.) This description can be represented as a set of weighted features (Smith & Medin, 1981). The features are weighted by their frequency in the category. For the category of birds, having wings and feathers would have a very high weight; eating worms would have a lower weight; living in Antarctica would have a lower weight still, but not zero, as some birds do live there.

The idea behind prototype theory is that when you learn a category, you learn a general description that applies to the category as a whole: Birds have wings and usually fly; some eat worms; some swim underwater to catch fish. People can state these generalizations, and sometimes we learn about categories by reading or hearing such statements (“The Komodo dragon can grow to be 10 feet long”).

When you try to classify an item, you see how well it matches that weighted list of features. For example, if you saw something with wings and feathers fly onto your front lawn and eat a worm, you could (unconsciously) consult your concepts and see which ones contained the features you observed. This example possesses many of the highly weighted bird features, and so it should be easy to identify as a bird.

If you were asked, “What kind of animal is this?” according to prototype theory, you would consult your summary representations of different categories and then select the one that is most similar to this image— probably a lizard! [Image: Adhi Rachdian, https:// goo.gl/dQyUwf, CC BY 2.0, https://goo.gl/BRvSA7]

This theory readily explains the phenomena we discussed earlier. Typical category members have more, higher-weighted features. Therefore, it is easier to match them to your conceptual representation. Less typical items have fewer or lower-weighted features (and they may have features of other concepts). Therefore, they don’t match your representation as well. This makes people less certain in classifying such items. Borderline items may have features in common with multiple categories or not be very close to any of them. For example, edible seaweed does not have many of the common features of vegetables but also is not close to any other food concept (meat, fish, fruit, etc.), making it hard to know what kind of food it is.

A very different account of concept representation is the exemplar theory (exemplar being a fancy name for an example; Medin & Schaffer, 1978). This theory denies that there is a summary representation. Instead, the theory claims that your concept of vegetables is remembered examples of vegetables you have seen. This could of course be hundreds or thousands of exemplars over the course of your life, though we don’t know for sure how many exemplars you actually remember.

How does this theory explain classification? When you see an object, you (unconsciously) compare it to the exemplars in your memory, and you judge how similar it is to exemplars in different categories. For example, if you see some object on your plate and want to identify it, it will probably activate memories of vegetables, meats, fruit, and so on. In order to categorize this object, you calculate how similar it is to each exemplar in your memory. These similarity scores are added up for each category. Perhaps the object is very similar to a large number of vegetable exemplars, moderately similar to a few fruit, and only minimally similar to some exemplars of meat you remember. These similarity scores are compared, and the category with the highest score is chosen.

Why would someone propose such a theory of concepts? One answer is that in many experiments studying concepts, people learn concepts by seeing exemplars over and over again until they learn to classify them correctly. Under such conditions, it seems likely that people eventually memorize the exemplars (Smith & Minda, 1998). There is also evidence that close similarity to well-remembered objects has a large effect on classification. Allen and Brooks (1991) taught people to classify items by following a rule. However, they also had their subjects study the items, which were richly detailed. In a later test, the experimenters gave people new items that were very similar to one of the old items but were in a different category. That is, they changed one property so that the item no longer followed the rule.

They discovered that people were often fooled by such items. Rather than following the category rule they had been taught, they seemed to recognize the new item as being very similar to an old one and so put it, incorrectly, into the same category.

ORGANIZATION OF CONCEPTS

SEMANTIC NETWORKS

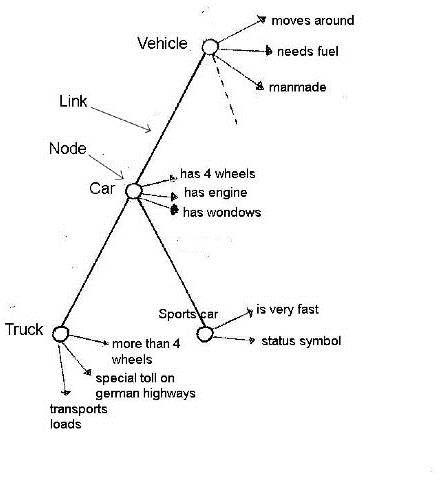

The Semantic Network approach proposes that concepts of the mind are arranged in a functional storage-system for the meanings of words. In a graphical illustration of such a semantic net, concepts of our mental dictionary are represented by nodes, which represent a piece of knowledge about our world. Links between the nodes indicate the relationship between concepts. The links can not only show that there is a relationship, they can also indicate the kind of relation by their length, for example. Every concept in the net is in a dynamical correlation with other concepts, which may have protoypically similar characteristics or functions.

COLLINS AND QUILLIAN’ S MODEL

One of the first scientists who thought about structural models of human memory that could be run on a computer was Ross Quillian (1967). Together with Allan Collins, he developed the Semantic Network with related categories and with a hierarchical organization.

In the picture on the right hand side, Collins’ and Quillian’s network with added properties at each node is shown. As already mentioned, the skeleton- nodes are interconnected by links. At the nodes, concept names are added. General concepts are on the top and more particular ones at the bottom. By looking at the concept “car”, one gets the information that a car has 4 wheels, has an engine, has windows, and furthermore moves around, needs fuel, is manmade.

These pieces of information must be stored somewhere. It would take too much space if every detail must be stored at every level. So, the information of a car is stored at the base level and further information about specific cars, e.g. BMW, is stored at the lower level, where you do not need the fact that the BMW also has four wheels, if you already know that it is a car. This way of storing shared properties at a higher-level node is called cognitive economy.

Semantic Network according to Collins and Quillian with nodes, links, concept names and properties. Information that is shared by several concepts is stored in the highest parent node. All child nodes below the information bearer also contain the properties of the parent node. However, there are exceptions. Sometimes a special car has not four wheels, but three. This specific property is stored in the child node. Evidence for this structure can be found by the sentence verification technique. In experiments participants had to answer statements about concepts with “yes” or “no”. It took longer to say “yes” if the concept-bearing nodes were further apart.

The phenomenon that adjacent concepts are activated is called spreading activation. These concepts are far more easily accessed by memory, they are “primed”. This was studied and backed by David Meyer and Roger Schaneveldt (1971) with a lexical-decision task. Participants had to decide if word pairs were words or non-words. They were faster at finding real word pairs if the concepts of the two words were near each other in a semantic network.

REFERENCES

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Allen, S. W., & Brooks, L. R. (1991). Specializing the operation of an explicit rule.Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 120, 3–19.

Anglin, J. M. (1977). Word, object, and conceptual development. New York, NY: W. W. Norton.

Berlin, B. (1992). Ethnobiological classification: Principles of categorization of plants and animals in traditional societies. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Brown, R. (1958). How shall a thing be called? Psychological Review, 65, 14–21.

Gelman, S. A. (2003). The essential child: Origins of essentialism in everyday thought. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Hampton, J. A. (1979). Polymorphous concepts in semantic memory. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 18, 441–461.

Hirschfeld, L. A. (1996). Race in the making: Cognition, culture, and the child’s construction of human kinds.

Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Horton, M. S., & Markman, E. M. (1980). Developmental differences in the acquisition of basic and superordinate categories. Child Development, 51, 708–719.

Keil, F. C. (1989). Concepts, kinds, and cognitive development. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Maddox, W. T., & Ashby, F. G. (2004). Dissociating explicit and procedural-based systems of perceptual category learning. Behavioural Processes, 66, 309–332.

Mandler, J. M. (2004). The foundations of mind: Origins of conceptual thought. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Mareschal, D., Quinn, P. C., & Lea, S. E. G. (Eds.) (2010). The making of human concepts. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

McCloskey, M. E., & Glucksberg, S. (1978). Natural categories: Well defined or fuzzy sets? Memory & Cognition, 6, 462–472.

Medin, D. L., & Ortony, A. (1989). Psychological essentialism. In S. Vosniadou & A. Ortony (Eds.), Similarity and analogical reasoning (pp. 179–195). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Medin, D. L., & Schaffer, M. M. (1978). Context theory of classification learning. Psychological Review, 85, 207– 238.

Mervis, C. B. (1987). Child-basic object categories and early lexical development. In U. Neisser (Ed.), Concepts and conceptual development: Ecological and intellectual factors in categorization (pp. 201–233). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Murphy, G. L., & Allopenna, P. D. (1994). The locus of knowledge effects in concept learning. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 20, 904–919.

Murphy, G. L., & Brownell, H. H. (1985). Category differentiation in object recognition: Typicality constraints on the basic category advantage. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 11, 70–84.

Norenzayan, A., Smith, E. E., Kim, B. J., & Nisbett, R. E. (2002). Cultural preferences for formal versus intuitive reasoning. Cognitive Science, 26, 653–684.

Rosch, E., & Mervis, C. B. (1975). Family resemblance: Studies in the internal structure of categories. Cognitive Psychology, 7, 573–605.

Rosch, E., Mervis, C. B., Gray, W., Johnson, D., & Boyes-Braem, P. (1976). Basic objects in natural categories.

Cognitive Psychology, 8, 382–439.

Rosch, E., Simpson, C., & Miller, R. S. (1976). Structural bases of typicality effects. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 2, 491–502.

Rosch, E. H. (1973). On the internal structure of perceptual and semantic categories. In T. E. Moore (Ed.), Cognitive development and the acquisition of language (pp. 111–144). New York, NY: Academic Press.

Smith, E. E., & Medin, D. L. (1981). Categories and concepts. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Smith, J. D., & Minda, J. P. (1998). Prototypes in the mist: The early epochs of category learning. Journal of

Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 24, 1411–1436.

Tanaka, J. W., & Taylor, M. E. (1991). Object categories and expertise: Is the basic level in the eye of the beholder? Cognitive Psychology, 15, 121–149.

Wisniewski, E. J., & Murphy, G. L. (1989). Superordinate and basic category names in discourse: A textual analysis. Discourse Processes, 12, 245–261.