6 Chapter 6. Memory in Context

CHAPTER 6: MEMORY IN CONTEXT

As we have seen, our memories are not perfect. They fail in part due to our inadequate encoding and storage, and in part due to our inability to accurately retrieve stored information. But memory is also influenced by the setting in which it occurs, by the events that occur to us after we have experienced an event, and by the cognitive processes that we use to help us remember. Although our cognition allows us to attend to, rehearse, and organize information, cognition may also lead to distortions and errors in our judgments and our behaviors.

CHAPTER 6 LICENSE & ATTRIBUTION

Kinds of Memory Biases; Misinformation Effect

Source: Laney, C. & Loftus, E. F. (2019). Eyewitness testimony and memory biases. In R. Biswas-Diener & E. Diener (Eds), Noba textbook series: Psychology. Champaign, IL: DEF publishers. Retrieved from http://noba.to/uy49tm37

Eyewitness Testimony and Memory Biases by Cara Laney and Elizabeth F. Loftus is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Condensed from original

Schematic Processing; Source Monitoring; Flashbulb Memories

Stangor, C. and Walinga, J. (2014). Introduction to Psychology – 1st Canadian Edition. Victoria, B.C.: BCcampus. Retrieved from: https:// opentextbc.ca/introductiontopsychology/

Introduction to Psychology – 1st Canadian Edition by Charles Stangor is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Changes and additions (c) 2014 Jennifer Walinga, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

Condensed from original; American spellings used; cultural references updated for American audience

Forgetting

Source: Spielman, R. M. OpenStax, Psychology. OpenStax CNX. http:// cnx.org/contents/4abf04bf-93a0-45c3-9cbc-2cefd46e68cc@12.2.

Psychology by Spielman (+ multiple authors) is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Condensed from original

Cover photo by Markus Spiske on Unsplash.

KINDS OF MEMORY BIASES

Memory is susceptible to a wide variety of biases and errors. People can forget events that happened to them and people they once knew. They can mix up details across time and place. They can even remember whole complex events that never happened at all. Importantly, these errors, once made, can be very hard to unmake. A memory is no less “memorable” just because it is wrong.

Some small memory errors are commonplace, and you have no doubt experienced many of them. You set down your keys without paying attention, and then cannot find them later when you go to look for them. You try to come up with a person’s name but cannot find it, even though you have the sense that it is right at the tip of your tongue (psychologists actually call this the tip-of-the-tongue effect, or TOT) (Brown, 1991).

Other sorts of memory biases are more complicated and longer lasting. For example, it turns out that our expectations and beliefs about how the world works can have huge influences on our memories. Because many aspects of our everyday lives are full of redundancies, our memory systems take advantage of the recurring patterns by forming and using schemata, or

For most of our experiences schematas are a benefit and help with information overload. However, they may make it difficult or impossible to recall certain details of a situation later. Do you recall the library as it actually was or the library as approximated by your library schemata? [Dan Kleinman, https://goo.gl/07xyDD, CC BY 2.0, https://goo.gl/BRvSA7] memory templates (Alba & Hasher, 1983; Brewer & Treyens, 1981). Thus, we know to expect that a library will have shelves and tables and librarians, and so we don’t have to spend energy noticing these at the time. The result of this lack of attention, however, is that one is likely to remember schema-consistent information (such as tables), and to remember them in a rather generic way, whether or not they were actually present.

SCHEMATIC PROCESSING: DISTORTIONS BASED ON EXPECTATIONS

We have seen that schemas help us remember information by organizing material into coherent representations. However, although schemas can improve our memories, they may also lead to cognitive biases. Using schemas may lead us to falsely remember things that never happened to us and to distort or misremember things that did. For one, schemas lead to the confirmation bias, which is the tendency to verify and confirm our existing memories rather than to challenge and disconfirm them. The confirmation bias occurs because once we have schemas, they influence how we seek out and interpret new information. The confirmation bias leads us to remember information that fits our schemas better than we remember information that disconfirms them (Stangor & McMillan, 1992), a process that makes our stereotypes very difficult to change. And we ask questions in ways that confirm our schemas (Trope & Thompson, 1997). If we think that a person is an extrovert, we might ask her about ways that she likes to have fun, thereby making it more likely that we will confirm our beliefs. In short, once we begin to believe in something — for instance, a stereotype about a group of people — it becomes very difficult to later convince us that these beliefs are not true; the beliefs become self-confirming.

Darley and Gross (1983) demonstrated how schemas about social class could influence memory. In their research they gave participants a picture and some information about a Grade 4 girl named Hannah. To activate a schema about her social class, Hannah was pictured sitting in front of a nice suburban house for one-half of the participants and pictured in front of an impoverished house in an urban area for the other half. Then the participants watched a video that showed Hannah taking an intelligence test. As the test went on, Hannah got some of the questions right and some of them wrong, but the number of correct and incorrect answers was the same in both conditions. Then the participants were asked to remember how many questions Hannah got right and wrong. Demonstrating that stereotypes had influenced memory, the participants who thought that Hannah had come from an upper-class background remembered that she had gotten more correct answers than those who thought she was from a lower-class background.

Our reliance on schemas can also make it more difficult for us to “think outside the box.” Peter Wason (1960) asked undergraduate students to determine the rule that was used to generate the numbers 2-4-6 by asking them to generate possible sequences and then telling them if those numbers followed the rule. The first guess that students made was usually “consecutive ascending even numbers,” and they then asked questions designed to confirm their hypothesis (“Does 102-104-106 fit?” “What about 404-406-408?”). Upon receiving information that those guesses did fit the rule, the students stated that the rule was “consecutive ascending even numbers.” But the students’ use of the confirmation bias led them to ask only about instances that confirmed their hypothesis, and not about those that would disconfirm it. They never bothered to ask whether 1-2-3 or 3-11-200 would fit, and if they had they would have learned that the rule was not “consecutive ascending even numbers,” but simply “any three ascending numbers.” Again, you can see that once we have a schema (in this case a hypothesis), we continually retrieve that schema from memory rather than other relevant ones, leading us to act in ways that tend to confirm our beliefs.

SOURCE MONITORING

One potential error in memory involves mistakes in differentiating the sources of information. Source monitoring refers to the ability to accurately identify the source of a memory. Perhaps you’ve had the experience of wondering whether you really experienced an event or only dreamed or imagined it. If so, you wouldn’t be alone. Rassin, Merkelbach, and Spaan (2001) reported that up to 25% of undergraduate students reported being confused about real versus dreamed events. Studies suggest that people who are fantasy-prone are more likely to experience source monitoring errors (Winograd, Peluso, & Glover, 1998), and such errors also occur more often for both children and the elderly than for adolescents and younger adults (Jacoby & Rhodes, 2006).

In other cases we may be sure that we remembered the information from real life but be uncertain about exactly where we heard it. Imagine that you read a news story in a tabloid magazine such as HELLO! Canada. Probably you would have discounted the information because you know that its source is unreliable. But what if later you were to remember the story but forget the source of the information? If this happens, you might become convinced that the news story is true because you forget to discount it. The sleeper effect refers to attitude change that occurs over time when we forget the source of information (Pratkanis, Greenwald, Leippe, & Baumgardner, 1988).

In still other cases we may forget where we learned information and mistakenly assume that we created the memory ourselves. Canadian authors Wayson Choy, Sky Lee, and Paul Yee launched a $6 million copyright infringement lawsuit against the parent company of Penguin Group Canada, claiming that the novel Gold Mountain Blues contained “substantial elements” of certain works by the plaintiffs (Cbc.ca, 2011). The suit was filed against Pearson Canada Inc., author Ling Zhang, and the novel’s U.K.-based translator Nicky Harman. Zhang claimed that the book shared a few general plot similarities with the other works but that those similarities reflect common events and experiences in the Chinese immigrant community. She argued that the novel was “the result of years of research and several field trips to China and Western Canada,” and that she had not read the other works. Nothing was proven in court.

Finally, the musician George Harrison claimed that he was unaware that the melody of his song My Sweet Lord was almost identical to an earlier song by another composer. The judge in the copyright suit that followed ruled that Harrison did not intentionally commit the plagiarism. (Please use this knowledge to become extra vigilant about source attributions in your written work, not to try to excuse yourself if you are accused of plagiarism.)

FALSE MEMORY

Some memory errors are so “large” that they almost belong in a class of their own: false memories. Back in the early 1990s a pattern emerged whereby people would go into therapy for depression and other everyday problems, but over the course of the therapy develop memories for violent and horrible victimhood (Loftus & Ketcham, 1994). These patients’ therapists claimed that the patients were recovering genuine memories of real childhood abuse, buried deep in their minds for years or even decades. But some experimental psychologists believed that the memories were instead likely to be false—created in therapy. These researchers then set out to see whether it would indeed be possible for wholly false memories to be created by procedures similar to those used in these patients’ therapy.

In early false memory studies, undergraduate subjects’ family members were recruited to provide events from the students’ lives. The student subjects were told that the researchers had talked to their family members and learned about four different events from their childhoods. The researchers asked if the now undergraduate students remembered each of these four events—introduced via short hints. The subjects were asked to write about each of the four events in a booklet and then were interviewed two separate times. The trick was that one of the events came from the researchers rather than the family (and the family had actually assured the researchers that this event had not happened to the subject). In the first such study, this researcher-introduced event was a story about being lost in a shopping mall and rescued by an older adult. In this study, after just being asked whether they remembered these events occurring on three separate occasions, a quarter of subjects came to believe that they had indeed been lost in the mall (Loftus & Pickrell, 1995). In subsequent studies, similar procedures were used to get subjects to believe that they nearly drowned and had been rescued by a lifeguard, or that they had spilled punch on the bride’s parents at a family wedding, or that they had been attacked by a vicious animal as a child, among other events (Heaps & Nash, 1999; Hyman, Husband, & Billings, 1995; Porter, Yuille, & Lehman, 1999).

More recent false memory studies have used a variety of different manipulations to produce false memories in substantial minorities and even occasional majorities of manipulated subjects (Braun, Ellis, & Loftus, 2002; Lindsay, Hagen, Read, Wade, & Garry, 2004; Mazzoni, Loftus, Seitz, & Lynn, 1999; Seamon, Philbin, & Harrison, 2006; Wade, Garry, Read, &

Lindsay, 2002). For example, one group of researchers used a mock-advertising study, wherein subjects were asked to review (fake) advertisements for Disney vacations, to convince subjects that they had once met the character Bugs Bunny at Disneyland—an impossible false memory because Bugs is a Warner Brothers character (Braun et al., 2002). Another group of researchers photoshopped childhood photographs of their subjects into a hot air balloon picture and then asked the subjects to try to remember and describe their hot air balloon experience (Wade et al., 2002). Other researchers gave subjects unmanipulated class photographs from their childhoods along with a fake story about a class prank, and thus enhanced the likelihood that subjects would falsely remember the prank (Lindsay et al., 2004).

Using a false feedback manipulation, we have been able to persuade subjects to falsely remember having a variety of childhood experiences. In these studies, subjects are told (falsely) that a powerful computer system has analyzed questionnaires that they completed previously and has concluded that they had a particular experience years earlier. Subjects apparently believe what the computer says about them and adjust their memories to match this new information. A variety of different false memories have been implanted in this way. In some studies, subjects are told they once got sick on a particular food (Bernstein, Laney, Morris, & Loftus, 2005). These memories can then spill out into other aspects of subjects’ lives, such that they often become less interested in eating that food in the future (Bernstein & Loftus, 2009b). Other false memories implanted with this methodology include having an unpleasant experience with the character Pluto at Disneyland and witnessing physical violence between one’s parents (Berkowitz, Laney, Morris, Garry, & Loftus, 2008; Laney & Loftus, 2008).

Importantly, once these false memories are implanted—whether through complex methods or simple ones—it is extremely difficult to tell them apart from true memories (Bernstein & Loftus, 2009a; Laney & Loftus, 2008).

MISINFORMATION EFFECT

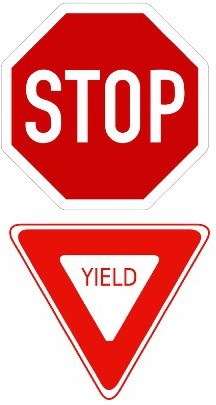

Eyewitness testimony is what happens when a person witnesses a crime (or accident, or other legally important event) and later gets up on the stand and recalls for the court all the details of the witnessed event. In an early study of eyewitness memory, undergraduate subjects first watched a slideshow depicting a small red car driving and then hitting a pedestrian (Loftus, Miller, & Burns, 1978). Some subjects were then asked leading questions about what had happened in the slides. For example, subjects were asked, “How fast was the car traveling when it passed the yield sign?” But this question was actually designed to be misleading, because the original slide included a stop sign rather than a yield sign.

Later, subjects were shown pairs of slides. One of the pair was the original slide containing the stop sign; the other was a replacement slide containing a yield sign. Subjects were asked which of the pair they had previously seen. Subjects who had been asked about the yield sign were likely to pick the slide showing the yield sign, even though they had originally seen the slide with the stop sign. In other words, the misinformation in the leading question led to inaccurate memory.

Misinformation can be introduced into the memory of a witness between the time of seeing an event and reporting it later. Something as straightforward as which sort of traffic sign was in place at an intersection can be confused if subjects are exposed to erroneous information after the initial incident.

This phenomenon is called the misinformation effect, because the misinformation that subjects were exposed to after the event (here in the form of a misleading question) apparently contaminates subjects’ memories of what they witnessed. Hundreds of subsequent studies have demonstrated that memory can be contaminated by erroneous information that people are exposed to after they witness an event (see Frenda, Nichols, & Loftus, 2011; Loftus, 2005). The misinformation in these studies has led people to incorrectly remember everything from small but crucial details of a perpetrator’s appearance to objects as large as a barn that wasn’t there at all.

These studies have demonstrated that young adults (the typical research subjects in psychology) are often susceptible to misinformation, but that children and older adults can be even more susceptible (Bartlett & Memon, 2007; Ceci & Bruck, 1995). In addition, misinformation effects can occur easily, and without any intention to deceive (Allan & Gabbert, 2008). Even slight differences in the wording of a question can lead to misinformation effects. Subjects in one study were more likely to say yes when asked “Did you see the broken headlight?” than when asked “Did you see a broken headlight?” (Loftus, 1975).

Other studies have shown that misinformation can corrupt memory even more easily when it is encountered in social situations (Gabbert, Memon, Allan, & Wright, 2004). This is a problem particularly in cases where more than one person witnesses a crime. In these cases, witnesses tend to talk to one another in the immediate aftermath of the crime, including as they wait for police to arrive. But because different witnesses are different people with different perspectives, they are likely to see or notice different things, and thus remember different things, even when they witness the same event. So when they communicate about the crime later, they not only reinforce common memories for the event, they also contaminate each other’s memories for the event (Gabbert, Memon, & Allan, 2003; Paterson & Kemp, 2006; Takarangi, Parker, & Garry, 2006).

The misinformation effect has been modeled in the laboratory. Researchers had subjects watch a video in pairs. Both subjects sat in front of the same screen, but because they wore differently polarized glasses, they saw two different versions of a video, projected onto a screen. So, although they were both watching the same screen, and believed (quite reasonably) that they were watching the same video, they were actually watching two different versions of the video (Garry, French, Kinzett, & Mori, 2008).

In the video, Eric the electrician is seen wandering through an unoccupied house and helping himself to the contents thereof. A total of eight details were different between the two videos. After watching the videos, the “co-witnesses” worked together on 12 memory test questions. Four of these questions dealt with details that were different in the two versions of the video, so subjects had the chance to influence one another. Then subjects worked individually on 20 additional memory test questions. Eight of these were for details that were different in the two videos. Subjects’ accuracy was highly dependent on whether they had discussed the details previously. Their accuracy for items they had not previously discussed with their co- witness was 79%. But for items that they had discussed, their accuracy dropped markedly, to 34%. That is, subjects allowed their co-witnesses to corrupt their memories for what they had seen.

IDENTIFYING PERPETRATORS

In addition to correctly remembering many details of the crimes they witness, eyewitnesses often need to remember the faces and other identifying features of the perpetrators of those crimes. Eyewitnesses are often asked to describe that perpetrator to law enforcement and later to make identifications from books of mug shots or lineups.

Here, too, there is a substantial body of research demonstrating that eyewitnesses can make serious, but often understandable and even predictable, errors (Caputo & Dunning, 2007; Cutler & Penrod, 1995).

In most jurisdictions in the United States, lineups are typically conducted with pictures, called photo spreads, rather than with actual people standing behind one-way glass (Wells, Memon, & Penrod, 2006). The eyewitness is given a set of small pictures of perhaps six or eight individuals who are dressed similarly and photographed in similar circumstances.

One of these individuals is the police suspect, and the remainder are “foils” or “fillers” (people known to be innocent of the particular crime under investigation).

If the eyewitness identifies the suspect, then the investigation of that suspect is likely to progress. If a witness identifies a foil or no one, then the police may choose to move their investigation in another direction.

This process is modeled in laboratory studies of eyewitness identifications. In these studies, research subjects witness a mock crime (often as a short video) and then are asked to make an identification from a photo or a live lineup. Sometimes the lineups are target present, meaning that the perpetrator from the mock crime is actually in the lineup, and sometimes they are target absent, meaning that the lineup is made up entirely of foils. The subjects, or mock witnesses, are given some instructions and asked to pick the perpetrator out of the lineup. The particular details of the witnessing experience, the instructions, and the lineup members can all influence the extent to which the mock witness is likely to pick the perpetrator out of the lineup, or indeed to make any selection at all. Mock witnesses (and indeed real witnesses) can make errors in two different ways. They can fail to pick the perpetrator out of a target present lineup (by picking a foil or by neglecting to make a selection), or they can pick a foil in a target absent lineup (wherein the only correct choice is to not make a selection).

Some factors have been shown to make eyewitness identification errors particularly likely. These include poor vision or viewing conditions during the crime, particularly stressful witnessing experiences, too little time to view the perpetrator or perpetrators, too much delay between witnessing and identifying, and being asked to identify a perpetrator from a race other than one’s own (Bornstein, Deffenbacher, Penrod, & McGorty, 2012; Brigham, Bennett, Meissner, & Mitchell, 2007; Burton, Wilson, Cowan, & Bruce, 1999; Deffenbacher, Bornstein, Penrod, & McGorty, 2004).

It is hard for the legal system to do much about most of these problems. But there are some things that the justice system can do to help lineup identifications “go right.” For example, investigators can put together high-quality, fair lineups. A fair lineup is one in which the suspect and each of the foils is equally likely to be chosen by someone who has read an eyewitness description of the perpetrator but who did not actually witness the crime (Brigham, Ready, & Spier, 1990). This means that no one in the lineup should “stick out,” and that everyone should match the description given by the eyewitness. Other important recommendations that have come out of this research include better ways to conduct lineups, “double blind” lineups, and unbiased instructions for witnesses (see Technical Working Group for Eyewitness Evidence, 1999; Wells et al., 1998; Wells & Olson, 2003).

FLASHBULB MEMORIES

You may have a clear memory of when you first heard about the 9/11 attacks in the United States in 2001, the upset win of the Giants over the Patriots at the Super Bowl for the 2007 NFL season, or the surprise result of the 2016 United States presidential election. This type of memory, which we experience along with a great deal of emotion, is known as a flashbulb memory — a vivid and emotional memory of an unusual event that people believe they remember very well (Brown & Kulik, 1977).

People are very certain of their memories of these important events, and frequently overconfident. Talarico and Rubin (2003) tested the accuracy of flashbulb memories by asking students to write down their memory of how they had heard the news about either the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks or about an everyday event that had occurred to them during the same time frame. These recordings were made on September 12, 2001. Then the participants were asked again, either one, six, or 32 weeks later, to recall their memories. The participants became less accurate in their recollections of both the emotional event and the everyday events over time. But the participants’ confidence in the accuracy of their memory of learning about the attacks did not decline over time. After 32 weeks the participants were overconfident; they were much more certain about the accuracy of their flashbulb memories than they should have been.

FORGETTING

As you’ve come to see, memory is fragile, and forgetting can be frustrating and even embarrassing. But why do we forget? To answer this question, we will look at several perspectives on forgetting.

ENCODING FAILURE

Sometimes memory loss happens before the actual memory process begins, which is encoding failure. We can’t remember something if we never stored it in our memory in the first place.

This would be like trying to find a book on your e-reader that you never actually purchased

and downloaded. Often, in order to remember something, we must pay attention to the details and actively work to process the information (effortful encoding). Lots of times we don’t do this. For instance, think of how many times in your life you’ve seen a penny. Can you accurately recall what the front of a U.S. penny looks like? When researchers Raymond Nickerson and Marilyn Adams (1979) asked this question, they found that most Americans don’t know which one it is. The reason is most likely encoding failure. Most of us never encode the details of the penny. We only encode enough information to be able to distinguish it from other coins. If we don’t encode the information, then it’s not in our long-term memory, so we will not be able to remember it.

Can you tell which coin, (a), (b), (c), or (d) is the accurate depiction of a US nickel? The correct answer is (c).

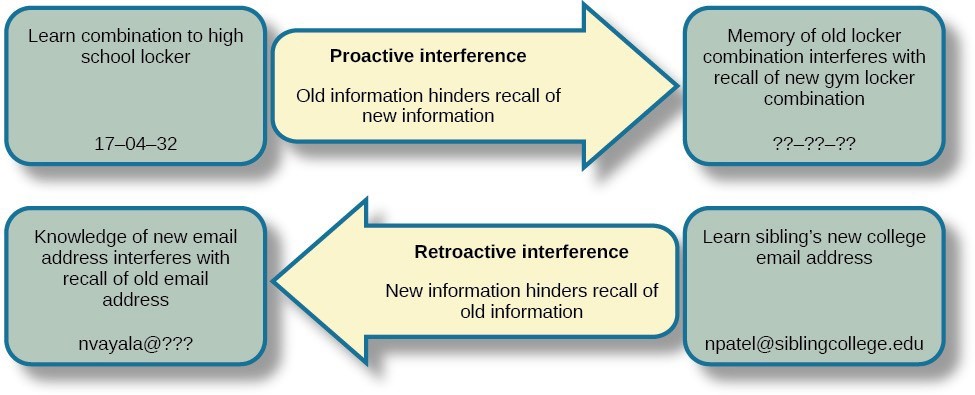

INTERFERENCE

Sometimes information is stored in our memory, but for some reason it is inaccessible. This is known as interference, and there are two types: proactive interference and retroactive interference. Have you ever gotten a new phone number or moved to a new address, but right after you tell people the old (and wrong) phone number or address? When the new year starts, do you find you accidentally write the previous year? These are examples of proactive interference: when old information hinders the recall of newly learned information.

Retroactive interference happens when information learned more recently hinders the recall of older information. For example, this week you are studying about Freud’s Psychoanalytic Theory. Next week you study the humanistic perspective of Maslow and Rogers. Thereafter, you have trouble remembering Freud’s Psychosexual Stages of Development because you can only remember Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs.

REFERENCES

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Alba, J. W., & Hasher, L. (1983). Is memory schematic? Psychological Bulletin, 93, 203–231.

Berkowitz, S. R., Laney, C., Morris, E. K., Garry, M., & Loftus, E. F. (2008). Pluto behaving badly: False beliefs and their consequences. American Journal of Psychology, 121, 643–660

Bernstein, D. M., & Loftus, E. F. (2009b). The consequences of false memories for food preferences and choices.

Perspectives on Psychological Science, 4, 135–139.

Bernstein, D. M., & Loftus, E. F., (2009a). How to tell if a particular memory is true or false. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 4, 370–374.

Bernstein, D. M., Laney, C., Morris, E. K., & Loftus, E. F. (2005). False memories about food can lead to food avoidance. Social Cognition, 23, 11–34.

Bornstein, B. H., Deffenbacher, K. A., Penrod, S. D., & McGorty, E. K. (2012). Effects of exposure time and cognitive operations on facial identification accuracy: A meta-analysis of two variables associated with initial memory strength. Psychology, Crime, & Law, 18, 473–490.

Braun, K. A., Ellis, R., & Loftus, E. F. (2002). Make my memory: How advertising can change our memories of the past. Psychology and Marketing, 19, 1–23.

Brewer, W. F., & Treyens, J. C. (1981). Role of schemata in memory for places. Cognitive Psychology, 13, 207–230.

Brigham, J. C., Bennett, L. B., Meissner, C. A., & Mitchell, T. L. (2007). The influence of race on eyewitness memory. In R. C. L. Lindsay, D. F. Ross, J. D. Read, & M. P. Toglia (Eds.), Handbook of eyewitness psychology, Vol. 2: Memory for people (pp. 257–281). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Brown, A. S. (1991). A review of tip of the tongue experience. Psychological Bulletin, 109, 79–91. Brown, R., & Kulik, J. (1977). Flashbulb memories. Cognition, 5, 73–98.

Darley, J. M., & Gross, P. H. (1983). A hypothesis-confirming bias in labeling effects. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 44, 20–33.

Deffenbacher, K. A., Bornstein, B. H., Penrod, S. D., & McGorty, E. K. (2004). A meta-analytic review of the effects of high stress on eyewitness memory. Law and Human Behavior, 28, 687–706.

Garrett, B. L. (2011). Convicting the innocent. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Heaps, C., & Nash, M. (1999). Individual differences in imagination inflation. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review, 6, 313–138.

Hyman, I. E., Jr., Husband, T. H., & Billings, F. J. (1995). False memories of childhood experiences. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 9, 181–197.

Jacoby, L. L., & Rhodes, M. G. (2006). False remembering in the aged. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 15(2), 49–53.

Laney, C., & Loftus, E. F. (2008). Emotional content of true and false memories. Memory, 16, 500–516. Lindsay, D. S., Hagen, L., Read, J. D., Wade, K. A., & Garry, M. (2004). True photographs and false memories.

Psychological Science, 15, 149–154.

Loftus, E. F., & Pickrell, J. E. (1995). The formation of false memories. Psychiatric Annals, 25, 720–725. Loftus, E. F., Ketcham, K. (1994). The myth of repressed memory. New York, NY: St. Martin’s Press.

Mazzoni, G. A. L., Loftus, E. F., Seitz, A., & Lynn, S.J. (1999). Changing beliefs and memories through dream interpretation. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 13, 125–144.

Nickerson, R. S., & Adams, M. J. (1979). Long-term memory for a common object. Cognitive Psychology, 11(3), 287–307.

Porter, S., Yuille, J. C., & Lehman, D. R. (1999). The nature of real, implanted, and fabricated memories for emotional childhood events: Implications for the recovered memory debate. Law and Human Behavior, 23, 517– 537.

Pratkanis, A. R., Greenwald, A. G., Leippe, M. R., & Baumgardner, M. H. (1988). In search of reliable persuasion effects: III. The sleeper effect is dead: Long live the sleeper effect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(2), 203–218.

Rassin, E., Merckelbach, H., & Spaan, V. (2001). When dreams become a royal road to confusion: Realistic dreams, dissociation, and fantasy proneness. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 189(7), 478–481.

Seamon, J. G., Philbin, M. M., & Harrison, L. G. (2006). Do you remember proposing marriage to the Pepsi machine? False recollections from a campus walk. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 13, 752–7596.

Stangor, C., & McMillan, D. (1992). Memory for expectancy-congruent and expectancy-incongruent information: A review of the social and social developmental literatures. Psychological Bulletin, 111(1), 42–61.

Steblay, N. M., & Loftus, E. F. (2012). Eyewitness memory and the legal system. In E. Shafir (Ed.), The behavioural foundations of public policy (pp. 145–162). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Talarico, J. M., & Rubin, D. C. (2003). Confidence, not consistency, characterizes flashbulb memories. Psychological Science, 14(5), 455–461.

Technical Working Group for Eyewitness Evidence. (1999). Eyewitness evidence: A trainer\’s manual for law enforcement. Research Report. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice.

Trope, Y., & Thompson, E. (1997). Looking for truth in all the wrong places? Asymmetric search of individuating information about stereotyped group members. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 73, 229–241.

Wade, K. A., Garry, M., Read, J. D., & Lindsay, S. A. (2002). A picture is worth a thousand lies. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review, 9, 597–603.

Wason, P. (1960). On the failure to eliminate hypotheses in a conceptual task. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 12(3), 129–140.

Wells, G. L., & Olson, E. A. (2003). Eyewitness testimony. Annual Review of Psychology, 54, 277–295.

Wells, G. L., Small, M., Penrod, S., Malpass, R. S., Fulero, S. M., & Brimacombe, C. A. E. (1998). Eyewitness identification procedures: Recommendations for lineups and photospreads. Law and Human Behavior, 22, 603– 647.

Winograd, E., Peluso, J. P., & Glover, T. A. (1998). Individual differences in susceptibility to memory illusions. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 12(Spec. Issue), S5–S27.